After a year of protest it’s time to re-examine what kind of Rio de Janeiro is emerging from the ‘city project.’

The widely (though not universally) held belief that Brazil had entered a new era of economic stability and social progress was severely dented in June of this year when enormous protests erupted across the country. Although less commented on in the mainstream national and international media, another dominant consensus was also thrown into question by the unrest: the idea that Rio de Janeiro was following a path towards improved urban governance and enhanced integration and social justice. In the wake of June 2013 these assumptions deserve, at the very least, a thorough re-examination.

The widely (though not universally) held belief that Brazil had entered a new era of economic stability and social progress was severely dented in June of this year when enormous protests erupted across the country. Although less commented on in the mainstream national and international media, another dominant consensus was also thrown into question by the unrest: the idea that Rio de Janeiro was following a path towards improved urban governance and enhanced integration and social justice. In the wake of June 2013 these assumptions deserve, at the very least, a thorough re-examination.

Rio’s resurgence and the city project

Before looking at this question it’s worth quickly revisiting how the city arrived at its current juncture. In 2003 Brazil came out of recession and began its most sustained period of growth since the 1970s, with Rio de Janeiro’s turnaround particularly notable after three decades of economic stagnation. In 2008, with the election of mayoral candidate Eduardo Paes, Rio’s three tiers of government fell into political alignment. These newly favorable economic and political conditions paved way for the development of what has been described as a ‘city project’ – a concerted effort to reshape the city physically, economically and socially. The final piece in the jigsaw came in October 2009 when Rio won the bid to host the 2016 Olympic Games.

The ‘city project’ consists of a wide range of policies across the fields of urban infrastructure, transport, housing and policing, which are designed and implemented by a diverse array of state and non-state actors. Some, like the Growth Acceleration Program (PAC) infrastructure development program, are federal policies that operate across Brazil. Others, like the Porto Maravilha regeneration scheme and the new Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) network, are public-private partnerships co-ordinated by the Rio city government under the umbrella of the ‘Cidade Olímpica’ (Olympic City). The Pacifying Police Units (UPPs), the flagship policing strategy focussed on Rio’s favelas, is run by the state governor’s office. They also run to different timetables and some (such as PAC and the UPPs) were underway before the successful Olympic bid. Nonetheless, there is enough overlap in coordination to conceive of the various components as part of a bigger whole. At the very least this is the way many of those involved – both those implementing the reforms, and residents on the receiving end of them – see it.

The ‘city project’ consists of a wide range of policies across the fields of urban infrastructure, transport, housing and policing, which are designed and implemented by a diverse array of state and non-state actors. Some, like the Growth Acceleration Program (PAC) infrastructure development program, are federal policies that operate across Brazil. Others, like the Porto Maravilha regeneration scheme and the new Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) network, are public-private partnerships co-ordinated by the Rio city government under the umbrella of the ‘Cidade Olímpica’ (Olympic City). The Pacifying Police Units (UPPs), the flagship policing strategy focussed on Rio’s favelas, is run by the state governor’s office. They also run to different timetables and some (such as PAC and the UPPs) were underway before the successful Olympic bid. Nonetheless, there is enough overlap in coordination to conceive of the various components as part of a bigger whole. At the very least this is the way many of those involved – both those implementing the reforms, and residents on the receiving end of them – see it.

The post-Third World city

The aims and assumptions guiding the city project broadly fall within what I call a ‘post-Third World city’ paradigm. This narrative places the current interventions within the context of two earlier periods of Rio de Janeiro’s history. The first of these is the rapid urbanization of the 1950s and 60s, which left large parts of the city lacking basic infrastructure and services, such as affordable housing, paved roads and public transport. The second is the era of so-called ‘urban fragmentation,’ when the strains of economic crisis fueled rising violence and the militarization of some urban boundaries during the 1980s and 90s. Although these were city-wide trends, in both cases favela areas tended to be most negatively affected.

Notwithstanding Rio de Janeiro’s, and Brazil’s, uniqueness, the processes of rapid urbanization and urban fragmentation conformed to trends observed by analysts in cities across the global south – or the ‘Third World’ as it was commonly referred to in the language of the time.

Notwithstanding Rio de Janeiro’s, and Brazil’s, uniqueness, the processes of rapid urbanization and urban fragmentation conformed to trends observed by analysts in cities across the global south – or the ‘Third World’ as it was commonly referred to in the language of the time.

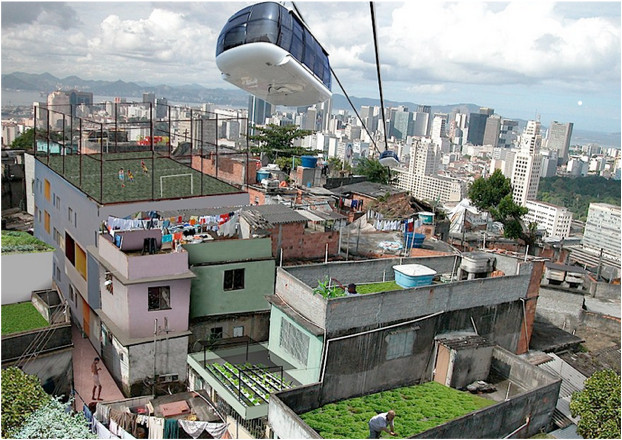

Within this narrative, the current set of programs traces its lineage to policies developed from the 1990s onwards in the context of such conditions, in Brazil and elsewhere. These include Rio’s own Favela Bairro program, which marked an apparently permanent shift in consensus from a policy of favela removal during the 1960s and 70s to a preference for on-site upgrading. The range of transport interventions (such as the BRT and favela cable cars), meanwhile, draw on innovations developed in other cities like Curitiba in southern Brazil, and Medellín and Bogotá in Colombia, that seek affordable solutions to challenges of urban mobility. The language that surrounds such policies consistently elevates the principle of integration. For example the Cidade Olímpica website affirms that: “the transformation of Rio into (an) Olympic City involves its social as well as physical integration.” Favela-targeted policies like Morar Carioca and UPP Social adopt similar language. Even pacification itself is framed around the idea of reducing barriers to integration and mobility between formal and informal areas.

The city of exception

While these ideas were dominant in political debate, media coverage and much academic research, a counter-narrative also took shape in some university departments and the burgeoning social movements that arose to resist some of the urban reforms. This set of ideas has been developed by numerous academics including Dr. Carlos Vainer at IPPUR-UFRJ (the planning institute at Rio’s Federal University). To Vainer and his colleagues, the origins of the city project are ascribed to a progressive transition, since the 1990s, from an ‘administrative’ to an ‘entrepreneurial’ model of urban governance. Under the latter, the primary aim of Rio’s urban authorities is to attract mobile international capital in competition with other ‘global cities,’ with the needs of existing residents taking a back seat.

Mega-events play a crucial role in such a strategy. In the short-term they attract businesses and tourists for the duration of the events themselves (although these are now widely seen as unable to compensate for the huge public investments made by host countries), while, in the long-term, they can serve to raise a city’s international profile. More significantly, the questionable legal status surrounding mega-events allows a suspension of legal norms and political contestation to create a ‘state of exception.’ This permits governments and their partners to ride roughshod over the rights of citizens in pursuit of their immediate and long-term aims using the pretense that top-down, closed-door and shotgun decisions are in the interest of the events and of the city.

Mega-events play a crucial role in such a strategy. In the short-term they attract businesses and tourists for the duration of the events themselves (although these are now widely seen as unable to compensate for the huge public investments made by host countries), while, in the long-term, they can serve to raise a city’s international profile. More significantly, the questionable legal status surrounding mega-events allows a suspension of legal norms and political contestation to create a ‘state of exception.’ This permits governments and their partners to ride roughshod over the rights of citizens in pursuit of their immediate and long-term aims using the pretense that top-down, closed-door and shotgun decisions are in the interest of the events and of the city.

According to the city of exception narrative the impacts of the city project are not integration, but in fact segregation. The creation of world-class (or ‘FIFA standard’) sporting stadiums leads to their elitization, by pricing out poorer fans. Meanwhile, the imperatives of hosting the events can be used as cover for eradicating land uses that fail to capture the full underlying ‘value’ – such as potentially lucrative areas occupied by favelas or public facilities. In a more general sense, an ‘entrepreneurial’ city tends to push poor residents to lower value areas by locating affordable housing in the distant urban periphery, and prioritizing transport and infrastructure for wealthier and important strategic areas. As for the interventions aimed at improving the integration of favelas, these are interpreted as a kind of ‘new hygienism’, attempting to civilize favela areas, or at least minimize their threat (perceived or real) to the rest of the city.

Conclusion

In wake of the June protests many of the issues that had largely been abandoned in mainstream political, media and academic debate were reopened. It is a credit to online forums including this one, and the opposing voices within the academy, that a rich set of alternative ideas have emerged from a period of powerful ideological hegemony. Even more importantly, grassroots movements emerging from endangered communities like the Aldeia Maracanã, Vila Autódromo and Rocinha, with its “Where is Amarildo?” campaign, have shown that resistance is possible and can have major results.

The new space they have created is hopeful, and must be exploited. This may require engaging with the progressive ideas at the core of the post-Third World city narrative, by highlighting how far actual interventions stray from these ideals, and continually pushing for the city project to deliver on its promise of public, rather than private, benefits. While a true democratization of the city project seems a long way off, it is already clear that its worst excesses can be challenged and defeated. With half a year until the World Cup, and three before the Olympics comes to town, there is much still to be decided and contested. The outcome will determine what kind of city Cariocas will live in for decades to come.

Matthew Richmond is currently conducting PhD research into neighborhood effects, social networks and the impacts of mega-events on two favelas. Read more on his blog.