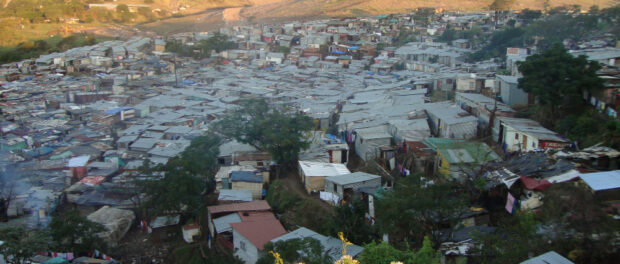

In 2007 the South African province of KwaZulu-Natal passed the KwaZulu-Natal Elimination and Prevention of Re-Emergence of Slums Act. Before the act became law, Abahlali baseMjondolo, a grassroots social movement whose name means “residents of the shacks,” produced a press release that stated: “The Bill uses the word ‘slum’ in a way that makes it sound like the places where poor people live are a problem that must be cleared away because there is something wrong with poor people… rather than the rich and the way in which they have made the poor… poor by a lack of development.”

For movement members, the word ‘slum’ carried dangerous stigmas about the area’s inhabitants, encouraging government policies to ‘eliminate’ such communities over working with residents to address their problems. Abahlali declared: “The people who live in the imijondolo must decide for themselves what they want their communities to be called.”

Resurgence of the term ‘slum’

The majority of English-language reports on Brazil during the intense media spotlight of the World Cup have translated the word ‘favela’ as ‘slum.’ It’s an unsurprising trend. Not only can the journalist or editor today find countless examples of their counterparts using that definition over recent years, but even Google Translate uncritically asserts that ‘favela’ is ‘slum’ and that ‘slum’ is ‘favela.’

Geography Professor Alan Gilbert writes that the term ‘slum’ was actually disappearing from use throughout the twentieth century, but that the United Nations “Cities Without Slums” initiative launched in 1999 pulled the word back into the center of development conversations, along “with all its inglorious associations.” In defining slums and quantitative goals for reducing them, Gilbert acknowledges that the UN is “engaging in the modern and perfectly proper practice of establishing ‘targets’ against which progress can be measured.” However, he argues that a ‘slum’ does not lend itself to being measured, in part because it is a relative, rather than absolute, concept.

The UN’s 2003 report, ‘The Challenges of Slums,’ states that slums are “too complex to define according to one single parameter” and “local variations among slums are too wide to define universally applicable criteria,” while “slums change too fast to render any criterion valid for a reasonably long period of time.” Still, the report offers an operational definition of a slum: “An area that combines, to various extents, the following characteristics (restricted to the physical and legal characteristics of the settlement, and excluding the more difficult social dimensions): inadequate access to safe water; inadequate access to sanitation and other infrastructure; poor structural quality of housing; overcrowding; insecure residential status.”

This does not match the reality of many of Rio’s favela residents who have access to running water, electricity, and garbage collection, while their houses are structurally sound. As noted on RioOnWatch, “under adverse possession legislation, residents have the legal right to occupy the land and in some favelas residents hold title.” Calling favelas–or indeed other such neighborhoods globally–‘slums’ conveys a misleading picture of these communities to international audiences.

Rejecting the label

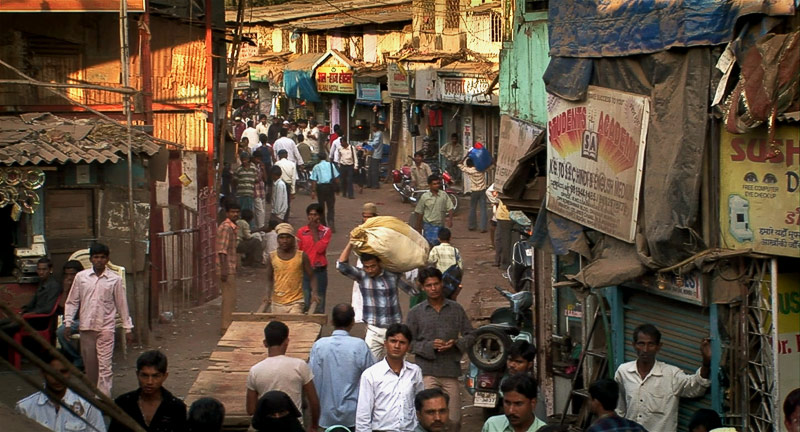

Labeling areas as ‘slums’ can also create a gap between residents’ understanding of their community and the perspective of outsiders who try to ‘help’ them. Anthropologist Rahul Srivastava and urban developer Matias Echanove discuss Dharavi, a district of Mumbai that has gained notoriety as one of Asia’s largest slums. They recall that they were “searching for slums” and found that “in every neighborhood residents said, ‘There is no slum here!’ They don’t think their house is situated in a slum.” However, they write that the media’s dominant portrayal of the district remains “as a wasteland with barely standing temporary structures; an immense junkyard crowded with undernourished people hopelessly disconnected from the rest of the world, surviving on charity and pulling the whole city’s economy backward.”

For Srivastava and Echanove, the portrayal as a ‘slum’ encourages top-down urban planning projects that ignore residents’ opinions. The stigma-heavy word obscures the area’s assets, such as how local residents’ construction of their own buildings leads to the development of neighborhoods that respond directly to local needs.

The ‘elimination of slum and blight’

In the United States, the labeling of areas as ‘slums’ has become a means to funding. The ‘elimination of slum and blight’ is encoded as one of the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s three national objectives. Accordingly, state governments allocate funding for projects that work towards that goal.

In 2013, city officials in Augusta, Georgia debated labeling the downtown area a slum, a designation that would make available US$26.5 million for renovations. According to a local paper: “City Administrator Fred Russell said…that it was unfortunate that Georgia legislators do require the characterization of a ‘slum’ for an area to receive special benefits but that suffering through the designation will be useful to continue downtown revitalization.”

Similarly, in 2013 in Rock Springs, Wyoming, the city’s urban renewal agency sought to label neighborhoods as ‘slum and blighted.’ According to a local news report, the director of community development, Laura Leigh, explained that the designation “[did] not mean all the properties within an area are dilapidated and run down.” However, residents “were livid with being included in a slum and blighted area,” leaving Leigh to question why the language could not be changed. As with Abahlali’s experience with the Slums Act, ‘slum’ language is employed to facilitate development projects at the cost of painting an inaccurate and stigmatizing picture of a community.