By 2050, around one third of the world’s population is expected to be living in informal settlements. The processes of informal production have an essential role in growing cities around the world, as rural to urban migration continues at a fast pace without the necessary availability of affordable housing. Although urban informality has often been associated with marginality, precariousness, social problems, and has generally been developing in the absence of basic public services and government intervention, there is no doubt that a complex diversity can be found in informal settlements. In fact, the various inherent qualities and assets in these environments could provide solutions to improve many issues of the formal urban environment.

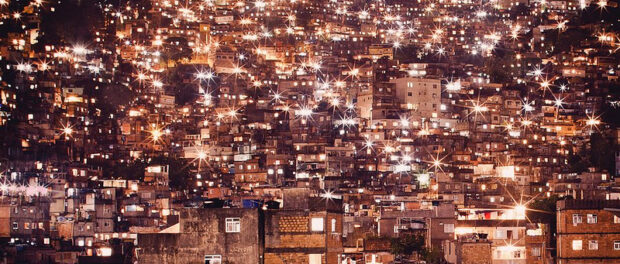

Rio de Janeiro is a strong example of a city where extreme wealth and poverty share the same territory, not only fragmented by a complex local topology, but also by historical social and political processes. Its informal neighborhoods, the favelas, are perhaps the most iconic image of urban informality itself, independently scattered in a continuous city.

The reality of favelas is still often accompanied by problems of sanitation, healthcare and education. However, the quality of life in informal neighborhoods can vary a lot, and their capacity to evolve quickly offers strong improvement potential. In some cases, if not the majority of them, favelas constitute a more efficient housing situation than Rio’s low-income government housing, with inherent architectural, economic and social qualities.

Flexibility

As a consequence of the historic lack of regulation that defines informality, favelas are partly characterized by their strong flexibility. The capacity to adapt to a specific context differentiates them from formal housing which is planned and built following a rational project with specific targets for the buildings, such as a specific number of residents or their integration to the city. In opposition, informal settlements are characterized by an organic and evolving architecture, constantly adapting to a topology, a context, and most importantly to the needs of residents.

While the rigidity of planned housing causes it to decay in the long term, favelas can be easily modified, facilitated by the use of cheap and largely accessible materials, allowing them to evolve quickly in their environment.

Affordable housing solution

Today, many of Rio’s favelas are experiencing a considerable rise in real estate values due to a property bubble in the city, the installation of Pacifying Police Units (UPPs) and the forces of gentrification. Yet, favelas constitute Rio’s affordable housing stock with communities located across the city including in the central and South Zones. This is a significant asset in a city with overloaded transit networks.

Different financing processes also distinguish formal and informal urban production in Rio de Janeiro. Planned housing, whether public or corporative, is financed through short or medium-term investments decided by small committees. This system can be deemed rigid and indeed hazardous, considering the risk of the ultimate failure of the project. This, in the case of government housing, means a large chance of wasted public funds.

In contrast, the building cost of an informal settlement is characterized by the economic independence of the residents, in both the construction and maintenance, and developed through a slow and collective design process. Houses are often built progressively springing from the entrepreneurship of each household, with families investing time and resources in the materials and the design of their home. Another consequence is a much better appropriation of the space by residents, involved in the maintenance of their dwelling–while most social housing projects are subject to faster degradation.

Sustainability

Although lacking the modern green buildings known for their individual environmental qualities, favelas generally have predispositions to sustainability in the way they are collectively organized. In fact, their characteristic low-rise density facilitates not only the installation of public services, but also implies a mixed-use urban composition, combining residential areas over commercial and social lots. This feature also means a proximity between the home, work and commercial spaces, and consequently reduced need for transportation. In addition, the pedestrian-oriented configuration, and the use of bicycles in low-lying favelas, also reduce transit issues and have a positive impact on environment.

Community eco-friendly initiatives are progressively appearing in informal areas of Rio de Janeiro, promoting responsible environmental behavior through the education of younger generations. Located in the dense informal urban environment of the Complexo do Alemão, the Verdejar Socioambiental organization is one of the most notable examples. Their use of energy-free domestic devices–from biodigesters and water cleansing systems to solar energy heating systems–demonstrates an evident trend and potential for sustainability with simple means.

Culture, community and sociability

Cultural and social production is perhaps the biggest advantage that favelas hold over state housing complexes. The display of such cultural creative vibrancy–through arts, music, dance, sport or food–within Rio’s urban environment is distinctive to its informal settlements, and constitutes a significant part of Rio de Janeiro’s cultural heritage. Long considered unworthy of attention, favelas today have become places where cultural events are an attraction for both local residents and visitors seeking to experience their unique social and cultural offerings.

Favelas’ high degree of sociability on a local scale is also due to their dense organization, promoting mixed-used properties and lowering the isolation possibilities by stimulating community exchanges, fostering strong local networks and encouraging collective action. The high visibility of rooftops and terraces, and the proximity of houses, also facilitates human interaction and bonds between neighbors.

The flexibility of informal settlements is also beneficial to the production of social interfaces, as a way to insert a specific activity in a stagnating neighborhood. City of God is a good example. As a social housing complex launched by the government in the 1960s, the project struggled to meet the newly relocated residents’ basic social needs, after having been planned as a mono-functional residential area. To activate the dead space between the generic housing blocks, the community informally implemented social and commercial interfaces, such as bars, kiosks and gyms, soon turning the area into a semi-informal hybrid neighborhood, ultimately becoming one of the most famous of Rio’s favelas today.

Aesthetics

The beauty of favelas is subjective and can be debated, and will be more aptly applied in reference to some areas in relation than others. However, many of these areas feature interesting aesthetic characteristics, and on different scales.

Historically, the first favelas were implemented on hills in central areas of the city, as the formal growth of the city constrained itself to the flat and easily constructible land. As a consequence, the locations of most informal settlements provide stunning panoramas and viewpoints of Rio de Janeiro’s landscape and coastline, stimulating in recent years–for better or worse–an influx of tourists visiting specific spots. The favelas’ slow and progressive growth in steep and elevated areas also follows the curves of the topology, not breaking the lines of natural landscapes as high-rises would.

The charm of a favela can also be owed to the spontaneity of its planning, leading to surprising and irregular spaces, breaking the monotony of a traditional city grid, while the limited range of construction material paradoxically harmonizes the visual impression of the environment. The various forms of street art and embellishments displayed in these communities, often made from simple resources, also contribute to a diverse visual panorama that has become iconic in popular culture.

Conclusion

Attempts to invest in and upgrade Rio’s favelas in Rio de Janeiro go back decades but are principally associated with the 1990s, through the Favela-Bairro program and later through the Growth Acceleration Program (PAC) and Morar Carioca initiatives. In most cases however, these programs impose rational solutions, completely new to the community and independent of the actual mechanics of a territory, rather than working with the existing qualities and specificities of the favela. Nevertheless, the improvement potential in Rio de Janeiro’s informal settlements is significant. The flexibility of these areas reveals their great capacity to adapt to different and evolving contexts. The favelas’ economic characteristics also prove to be very viable. Their low-rise density, mixed-used composition and disposition for public transportation and walkability are all attributes championed by postmodern urban design movements. But the strongest asset of a favela is its community: encouraging collective action and representative of a strong cultural identity, favela-style development today is inspiring opportunities to overcome the limits of formal planned construction.