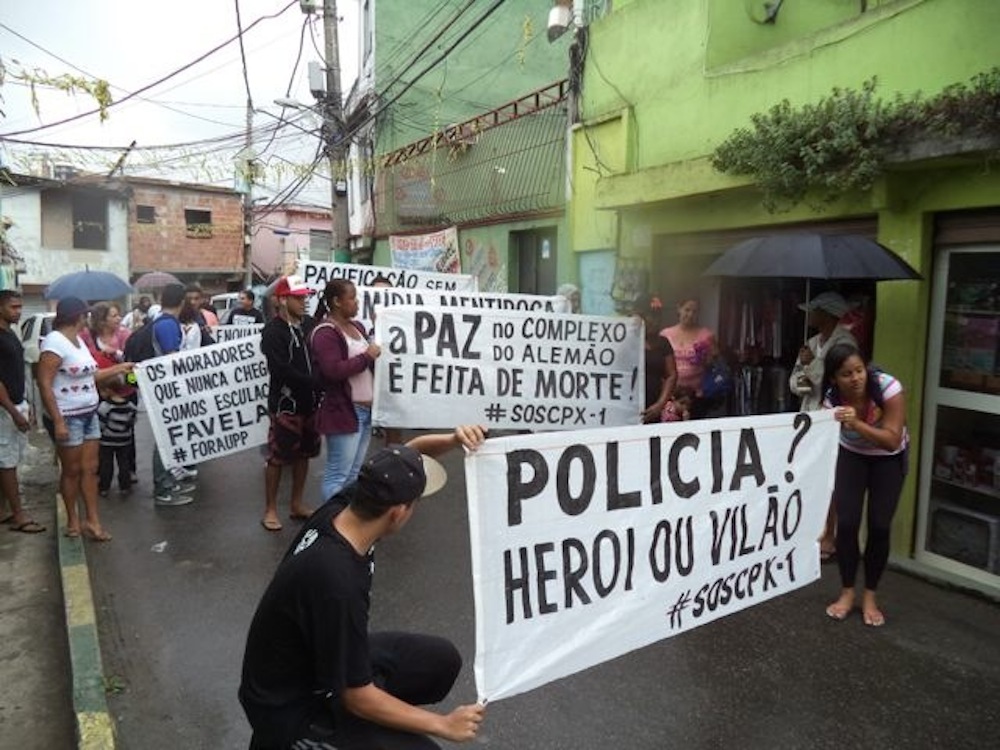

On August 9, unarmed American teenager Michael Brown was shot to death by a policeman in Ferguson, Missouri, unleashing immediate protest. On the same day, residents of Complexo do Alemão in Rio de Janeiro organized a march to demand an end to recent shootings that have injured and killed unarmed community residents.

Brown’s death has left many Americans outraged, but sadly not surprised. The case is one among several recent incidents of young black men dying at the hands of the police in the US. What caught more Americans off guard was the militarized force with which the police responded to the ensuing protests in Ferguson. With protesters and journalists arrested and assaulted, onlookers across the country decried the heavy-handed policing that seemed to belong to a previous era, to a different part of the world.

In Brazil, in contrast, neither high death rates of innocent poor black citizens nor oppressive police tactics are a surprise to citizens. In Rio de Janeiro in particular, harboring some of Brazil’s most violent police and most extreme inequality, what happened in Ferguson is the city’s modus operandi, its bread-and-butter. This even applies to many of Rio’s “community policing,” or Pacifying Police Units (UPP) program sites, a program launched in 2008 that establishes a constant police presence in selected favelas around the city. In Alemão, for example, police stand at strategic street corners with rifles pointed down narrow alleyways or over walls. Residents, including young children, pass through such alleyways on their way to schools, shops or work, on a daily basis. Just last night, August 24, inhabitants of the favela complex took to social media to report “intense shooting” that saw people running for their lives and animals wounded and killed.

Critics argue that this approach to improving safety inherently criminalizes the city’s low-income, majority-black favela residents.

Much as media in the United States have analyzed the startling appearance of Ferguson and St. Louis police armed and uniformed for war, there was similar discussion of the police attire and armament during this year’s World Cup in Brazil. Military Police, sporting ‘Robocop’ gear reminiscent of Darth Vader, responded to demonstrations against the tournament with tear gas, rubber bullets, and batons. Some activists were preemptively arrested before the protests even began, criminalized without actually committing a crime, for taking part in the democratic process. Last year, the incipient protest movement that took 300,000 Rio citizens to the streets was quickly squelched by a deeply troubling police operation.

Following the massive protests during the 2013 Confederations Cup, the Brazilian government prepared for the World Cup by expanding the police’s arsenal with purchases from Israeli military weapons companies. Similarly, local law enforcement agencies across the United States receive military level equipment from the Pentagon, a process that many Americans only realized as events unfolded in Ferguson.

At a recent debate on police violence and the criminalization of poverty and social movements held at the Fluminense Federal University (UFF), participants traced evidence of criminalizing narratives and propaganda throughout Brazilian history to try to explain the (mis)use of violence and police militarization in Brazil today. Speaker Thiago Melo, lawyer and director of the Human Rights Defenders Institute, argued that, while the use of heavy equipment, lethal weaponry and warfare vehicles in the face of civilians should be indubitably unconstitutional, the abuse of non-lethal weapons constitutes an equally clear case of illegality.

The Brazilian government may have cited heightened security demands during the World Cup as the main reason for bulking up security forces, but sports and politics writer Dave Zirin points out that new high-tech gadgets will not be put aside now that the World Cup is over. New instruments will become part of the routine equipment and remain long after the mega-event, or the “state of emergency,” has ended. Henrique Vieira, a professor, theologian and militant who participated in the UFF debate, elaborated that the need for expediency during an “emergency” situation like a mega-event opens the political space for exceptional measures, such as the suspension of inalienable rights. This state of emergency both nurtures and is nurtured by efforts to normalize the criminalization of segments of the population.

Participants in the UFF debate raised questions about Ferguson, wondering why similar tragedies in Brazil have not stirred the same global attention. It is not only in academic environments that Brazilians have tied the two cases together. The protesters at the August 9 march in Rio sprayed #SOSComplexoDoAlemao around the favela, sparking a Twitter campaign which provokes natural comparison between the two cases.

Blogger Rio Gringa has noted that the tweet contents will be immediately familiar to anyone following the Michael Brown case. Many Twitter campaign participants noted that it is “young, black, poor men who die the most in this war.” One participant stated: “I want my kids to have the freedom to come and go at whatever time without being afraid of becoming a statistic,” a statement echoed by African-American parents across the United States. Just as discussions in the United States have debated the intersecting roles of race and class dictating the disproportionate numbers of young black men shot by police, #SOSComplexoDoAlemão tweets also see both race and class at play in the criminalization of favela residents. “Poverty is not a crime,” one participant declared.

Although most Americans are unlikely to know about #SOSComplexoDoAlemao, Brazilian activists are certainly aware of the Twitter campaigns resulting from events in Ferguson, notably #DONTSHOOT. The independent reporting collective Mídia NINJA has used #DONTSHOOT to call out police violence “in Ferguson, in Brazil, in Palestine” and to demand an end to the “genocide against poor black people in Brazil going on now.”

Black Women of Brazil, a blog “dedicated to Brazilian women of African descent,” also used #DONTSHOOT to communicate the March Against the Genocide of Black People on August 22. This event was actually a number of marches in various locations across the country, with the Rio march taking place in Manguinhos.

While Americans are questioning domestic policies, structures and inequalities to make sense of events in Ferguson, these Brazilian activists are deliberately highlighting global parallels as key insights to understanding the processes of criminalization and police militarization in Brazil, and worldwide.