For the original in Portuguese, by Maria Eduarda Chagas, published in Estadão, click here.

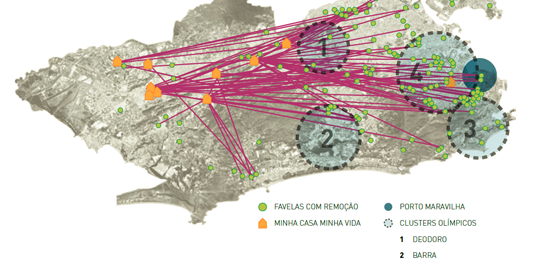

In the pre-Olympics period, 67,000 people were forced to leave their homes, more than were evicted under both Pereira Passos and Lacerda administrations–those most notable for evictions in Rio’s history–put together.

A little over one year ahead of the Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, one book hits the shelves that shows the urban planning effects of this event and the 2014 World Cup on the city. The book SMH 2016: Removals in Olympic Rio de Janeiro maps forced evictions by the Mayor Eduardo Paes administration from 2009 to 2013—more than 65,000—and concludes that Paes oversaw more evictions than his predecessors [most associated with evictions] Pereira Passos (1900s) and Carlos Lacerda (1960s) combined.

The work is the result of a final-year research project by undergraduate Architecture and Urbanism student Lucas Faulhaber, who has since graduated from the Fluminense Federal University (UFF). Journalist Lena Azevedo and photographer Luiz Baltar were invited by publishing house Mórula Editorial to join the project and the book emerged. In the second part of the book, Lena conducts interviews with 12 residents who had to leave their homes. The preface is signed by Raquel Rolnik, professor at the University of São Paulo and UN rapporteur on the right to adequate housing from 2008 to 2014.

Faulhaber’s original intention was to prove that, while many use the lack of planning to justify the so-called ‘divided city,’ exclusion is in fact mainly the result of an urban planning strategy. “By investigating the development of plans, laws and infrastructure projects in Rio, I could identify huge numbers of planned dispossessions of lands in place and later of removals that were considered fundamental to the implementation of projects, especially in recent years,” he explains.

The architect says there is a process of violations of rights that is obscured by the Olympics. “The removal of the poorest from their places of residence is always considered a fundamental pre-requisite for the enhancement of the region; [as the saying goes] ‘eggs must be broken to make an omelette.’ This is how it was with the boot-down of Pereira Passos, with the fires in the South Zone favelas during the Lacerda government, and now it is no different during the preparations for the World Cup and Olympics,” he says.

Since the start of the building and construction works for the World Cup and the Olympic Games, Eduardo Paes has been questioned about forced evictions. He has repeated that these infrastructure works are not exclusively for the sporting events, but to benefit the population. In 2014, when Amnesty International received a petition for an end to forced evictions, Paes admitted that the City had not “spoken enough” with residents removed from their houses due to the construction of the express bus lines Transcarioca and TransOlímpica.

Earlier, in 2013, in an interview with Carta Capital magazine, the mayor justified the evictions. “Most of the removals are formal expropriations in middle-class and lower-middle-class areas. Removals in favelas usually occur in areas prone to hazards. We offer what is called a (monthly) social rent payment of R$400 (US$130), indemnities, or a Minha Casa Minha Vida [social housing] unit. It is true that many of the [social housing] apartments are in the West Zone of the city. But they can choose. They say that the rent is low, but I have 9,000 families enrolled in the program. If they disagree with the amount given as compensation, they can go to court. Actually, the compensations we offer are above value, but since it’s for a good cause nobody complains about it,” he said at the time.