Since winning the Olympic bid in 2009 and hosting the 2014 World Cup, the city of Rio de Janeiro has gone through immense urban transformations that have disrupted and changed the lives of its millions of residents. With one year to go to the 2016 Olympic and Paralympic Games, RioOnWatch offers this summary of what you need to know about the preparations for the global event and how it has affected residents across Rio de Janeiro.

Forced Evictions

The topic of forced evictions is a frequent one when it comes to building infrastructure for global sporting events, and Rio de Janeiro has seen some of the highest rates of forced evictions associated with any mega-event. Most striking, however, Rio’s pre-Olympic period saw the largest number of evictions and displacements in the City’s history: according to the book SMH 2016: Removals in Olympic Rio de Janeiro by architect Lucas Faulhaber and journalist Lena Azevedo, more than 67,000 people were evicted just from 2009 to 2013–this is more than were evicted under both Pereira Passos and Lacerda administrations (those most notable for evictions in Rio’s history) put together. In an interview with Brasil de Fato, translated and published by RioOnWatch, Faulhaber argues that the Olympics are not the real reason for the evictions but that the sporting event is being used to legitimize them, as well to press ahead with the timeline. Mandates for public consultation have been ignored due to the perceived urgency of ‘preparing the city for the Games.’

One of the most dramatic forced evictions stories is that of Vila Autódromo, a community that has been standing for more than 40 years and which neighbors the future Olympic Park. Titles were provided to residents nearly two decades ago by the state government, but the Mayor claims these were a sham and that it must be removed for Olympic works even though the approved Olympic design maintained the community in place. It is widely held among close followers of the case, rather, that the community was used as currency to convince developers to carry out Olympic works, knowing the Olympic Park and surrounding areas will be repurposed for luxury developments after the Games.

Always a safe community, with a large number of residents who chose the community for its tranquility, Vila Autódromo is now a mixture of half-demolished houses and homes populated by residents who are still resisting the City’s negotiation tactics. After a long process of negotiation made possible thanks to the community’s legendary resistance–that has included treacherous divide and conquer tactics–over 590 of the 760 properties in the community have now been vacated. Although many people who were displaced received compensation or were moved to public housing, the destruction of a valuable community is being mourned by families who are still resisting, insisting that the Mayor’s promise that those who desired to stay would be permitted to do so, must be upheld.

Although Vila Autódromo has been central in the discussion of forced evictions, dozens of communities have suffered with Olympic and World Cup works and the opportunity for reconfiguring the city that has come with these mega-events. About one kilometer away from the Olympic Park, Vila União de Curicica was first told it would receive investments and upgrades, then told all residents would be removed into Minha Casa Minha Vida public housing for the construction of the Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system. In April of this year, the first demolitions took place without any communication or justification from authorities. Writing for RioOnWatch in May of 2014, Stefan Johnson concluded that the BRT “has led to the eviction and displacement of entire communities, including Largo do Campinho, Vila Harmonia, Restinga and Vila Recreio II.”

As we approach the Games, RioOnWatch noticed a worrying trend of lightning evictions–forced evictions with little or no warning and tenuous court approval–when several communities across Rio saw violent scenes of people being dragged out of their homes to see them demolished.

Other communities that suffered forced evictions not mentioned above and covered by RioOnWatch:

- Providência

- Santa Marta

- Metrô-Mangueira

- Manguinhos

- Indiana

- Vila Laboriaux, Rocinha

- Largo do Tanque

- Horto

- Pavão-Pavãosinho

- Estradinha

- Vila Taboinha

- Vila das Torres

- Morro do Bumba

- Favelinha da Skol, Alemão

- Babilônia

- Colônia Juliano Moreira

Evictions or threats of eviction have also been made in Muzema, Cantagalo, Vale Encantado, Tavares Bastos, Vidigal, Pedra Branca communities, and a number of others covered by RioOnWatch. In all cases, even in those where evictions are held by the authorities to be in residents’ interest, there is zero participation.

Gentrification

With no regulation on housing prices in the city that has recently experienced the greatest cost of living increase worldwide, pressure has mounted on centrally-located favelas, with gentrification introduced into the popular lexicon in 2011, though many residents prefer to refer to it as remoção branca (or “white removal”). Vidigal (and other pacified communities in the wealthy and touristic South Zone) are most impacted, as they attract attention from foreigners and speculators, with rumors that even David Beckham and Madonna have bought properties in the area.

Beyond gentrification, displacement due to cost of living increases has affected every single established favela in Rio de Janeiro, regardless of location or pacification. In Complexo do Alemão and Maré in the North Zone, increases in rent have led thousands to abandon their homes.

Different from the case with forced evictions, reliable numbers on those displaced due to gentrification and rent-induced-displacement are not yet available. What has been widely documented, however, are the increasing numbers of urban occupations–São Gonçalo, Nova Tuffy and Telerj, just to name a few–and the formation of new favelas on the urban fringe, or piling up of families in fewer dwellings, as the most vulnerable community residents are left without access to Rio’s affordable housing stock–its favelas.

Public Security

The Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) program constitutes Rio’s Military Police’s first major attempt at police reform in its 200 year history. The first UPP was installed in December 2008 as a test program to decrease violence in favelas and drive out drug traffickers. Soon, implementing UPPs all over the city became a priority because of the upcoming 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympics. While assessing the effectiveness of the program in 38 different communities is a complex task, and implementation varies widely from community to community–Patrick Ashcroft examined each installation in a series of articles–its failures are glaring.

A report released by Amnesty International this week revealed that Rio de Janeiro police killed 1,519 people in five years, of which 75% were black males aged between 15 and 29. In fact, one in six killings in Rio is conducted by on-duty police. Put another way, Rio’s Military Police kill one person for every 23 arrested, a statistic which is shocking when put into context: in the USA this ratio is 1:37,000. Amnesty’s report is consistent with resident reports of police violence and constant shootings that often take place in favelas across the city despite the UPP installations. For example, in Complexo do Alemão the year of 2015 started off with 100 days of uninterrupted shootings that claimed the life of 10-year-old boy Eduardo de Jesus Ferreira, shot on his own doorstep by a UPP officer. This week, community activist and member of Coletivo Papo Reto Raull Santiago reported that Complexo do Alemão has had shootings every day for the last three weeks.

Environmental Impacts

City promises for an environmental Olympic legacy included the planting of 24 million trees to offset carbon emitted for the Games, and a dramatic decrease in pollution of the Guanabara Bay by 80%. Neither promise has been kept and officials have admitted that the Guanabara Bay target is unreachable in time for the Games, while the World Health Organization is now involved in virus testing in the Bay.

Meanwhile, in the Serra da Misericórdia, branded “the lungs of Rio’s North Zone,” community groups have been waiting for R$15 million of funding since 2012 that would be used for preservation and which would service the air breathed in Rio’s densest zone.

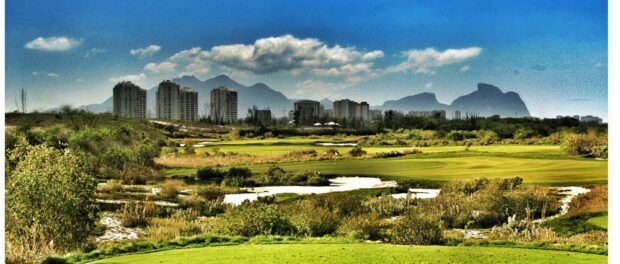

The Olympic golf course is being built on “1 million square meters of protected Atlantic Forest on the edge of the Marapendi lagoon in Barra da Tijuca,” writes Elena Hodges. Hodges reports that the City government ignored an “array of laws,” from federal to municipal to build the course and puts forward that the area’s 300 identified species will be threatened by the works.

Meanwhile, the Olympic Athlete’s Village–named Ilha Pura, or ‘Pure Island,’ a gated community larger than the Rio neighborhood of Leblon–is being billed the first LEED-ND-certified development in Brazil. LEED is the most widely recognized certification of green buildings worldwide, while LEED-ND rates the sustainability of entire neighborhoods. Having just made the cut, Ilha Pura’s development is billed as an entirely sustainable urban oasis. However, Ilha Pura is inconsistent with LEED-ND goals of focusing growth and redevelopment in existing urban areas that are already served by infrastructure, while avoiding sensitive water resources and habitat areas, and not encroaching on agricultural land and floodplains. A 50% owner in Ilha Pura, Carlos Carvalho, was this week described in The Guardian due to his expectation of grossing $1 billion from real estate developments across Rio leading up to the Olympics.

Conclusion? The city is being remade to the benefit of a small elite, at the expense of the urban poor.