For the original article in Portuguese by Thiago Guimarães published on BBC Brasil click here.

During this final stretch to the Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, deadlines become shorter and pressure mounts on communities that resist making way for public works associated with the Games. In all, 22,000 families have already been resettled in the city from 2009 to 2015, as the result of new ventures or because they are at risk. And 74% of these people were given homes through the Minha Casa Minha Vida (MCMV) program, a trademark of Dilma Rousseff’s presidential mandate.

“This [homeownership] is a dream that has accompanied humanity since the beginning of time, a place where you are safe and build your future and your life,” said Rousseff last month upon handing over more houses to the program, using a reference that reoccurs often in the President’s speeches.

A recent study, however, has investigated how this new housing program has impacted the livelihoods of beneficiaries, and found that the program is not always synonymous with progress and economic stability, as preached by the official narrative.

When interviewing residents in five communities in Rio, all in the crosshairs of removals or already resettled in MCMV units, sociologist Melissa Fernandez Arrigoitia of LSE (the London School of Economics) met people who faced new financial difficulties—whether because of new bills to pay, or due to the distance from their old jobs, or as a result of new transport-related expenses.

For the LSE Department of Geography researcher, who is still working to quantify the dozens of interviews conducted, a “resettlement does not always ‘settle’ the brutality and exploitation that characterize many removals.” “These injustices can continue, masked by new shapes and forms,” she adds.

Fernández Arrigoitia says that there is still little information on how the beneficiaries support themselves once they move—and the research shows that people are losing or changing jobs. The researcher presented her work at a recent conference at the Brazil Institute at King’s College London.

“Most people started to work at home in small businesses, such as selling cleaning products, beauty products, computer repairs. And their incomes shrank, but expenses increased with bills, fees, and consumer items,” she says.

One-hour commutes that turned into daily journeys of up to six hours explain the job turnover, says the sociologist. “Some people cited the physical exhaustion caused by the distance. One woman had a car, but almost died when she crashed the vehicle one day. She quit her job and set up a home business.”

“Sea of roses”

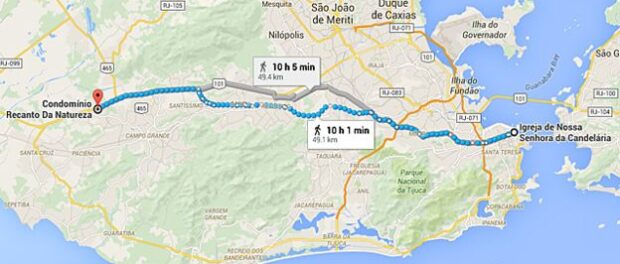

Data collection took place from August 2013 to February 2014. One of the sites visited was the Recanto da Natureza, a set of 20 blocks of 384 apartments of 44m2 each. Located in Campo Grande (in the West Zone), about 50 km from downtown Rio, the condominium received residents from risk areas and land invasions.

“Whoever said this place was a sea of roses was lying. They removed people from where they were to put them here, and everything has a cost,” one resident said to Fernández Arrigoitia’s team.

The researcher reports hearing residents with symptoms of depression who associated their feelings of isolation with the changes. And she stresses that the program needs to consider the emotional impact and mental health of these removals.

“One-hour commutes that turned into daily journeys of up to six hours explain the job turnover, says the sociologist. ‘Some people cited the physical exhaustion caused by the distance. One woman had a car, but almost died when she crashed the vehicle one day. She quit her job and set up a home business.'”

“This kind of report questions the official narrative of these projects, as a provider of something better in terms of human development. I am not denying that they offer something better in terms of housing, and many people have confirmed this. The objective of the research is to broaden this debate, to show that it is more complex than the story that it is a good thing, period,” she says.

Launched in 2009, Minha Casa Minha Visa has become part of the main electoral platform of Dilma. It serves families with monthly incomes of up to R$1,600 (around US$408), and since its beginnings the program has delivered 2.3 million homes, according to the official toll—with 1.6 million units which remain to be built in the second phase of the initiative.

The program’s projects occur mainly in areas donated or released by states and municipalities, and with the current budget cuts—R$4 billion in resources was lost in 2015 (or 28% from 2014, compared to August)—the program’s third phase is still on standby.

Flooded

Another focus of this research was on Bairro Carioca, a set of 2,240 units housing 11,000 people in the North Zone. The complex, one of the few MCMV projects near the city center in Rio (about 10km), suffered flooding in the summer of 2013, shortly after being occupied by families taken from areas of risk.

“They said they felt very badly treated in the days after those floods. They received cheap things such as blankets and mattresses, just to deal with the direct consequences. They felt it was a reinforcement of discrimination: ‘The government made these houses that were meant to be great, but they flooded, we lost many things, and now we receive cheap things to just deal with this.’ They felt insulted in that sense,” says Fernández Arrigoitia.

For her, the program may end up perpetuating a state of marginalization of its beneficiaries.

“Something came from residents, excluded for a long time from the city, stigmatized and marginalized as citizens, and they felt that this change was not changing that stigma, it simply changed the language, as in changing the term ‘slum’ to ‘community’. Furthermore, there’s our interpretation of what we see. And we saw spaces clearly delineated by walls and fences, or very remote geographically, in spaces disconnected from anything resembling a city. ”

Olympics

In the opinion of the sociologist, in the specific case of Rio, expropriations and removals related to the works of the 2016 Olympic Games end up repeating problems seen in prior housing policies in Brazil.

“I heard technicians and colleagues involved in these programs on how it was done, with violent expropriations and human rights violations. It’s amazing how it is repeating itself. The local residents are not consulted in the right way, they do not receive a range of options to choose from, and are not adequately compensated for land that will generate a lot of money. A lot of these issues are similar to those of the 1960s and 1970s.”

So, is this process of social exclusion the result of a lack of general planning or urban planning as argued, for example, by critics of current removals in Rio?

For Fernandez Arrigoitia, it’s “a bit of both… The way housing policies are designed and implemented, consciously or unconsciously, reproduces social exclusion. The rules of the game are already given, and generally favor those who already benefit from the system.”

“I heard technicians and colleagues involved in these programs on how it was done, with violent expropriations and human rights violations. It’s amazing how it is repeating itself. The local residents are not consulted in the right way, they do not receive a range of options to choose from, and are not adequately compensated for land that will generate a lot of money. A lot of these issues are similar to those of the 1960s and 1970s.”

The researcher points out that such traits become more evident with the acceleration of urban projects—and the economic pressures associated with them—to meet the deadlines of mega-events like the World Cup and the Olympics.

Short-term outlook

By analyzing differences between the social housing models in England and Brazil, she points to the predominance of a short-term outlook.

“In the case of MCMV, and this has been widely documented, the program benefits contractors who receive large areas to develop and profit off of from the government, because these homes are sold. This is not social rent like in England, where the government can retain the value of land through rent. What they are doing is giving away land, contractors profit, beneficiaries gain a home, but once the unit is sold, the subsidy (the land given by the government) can no longer be reused.”

She considers, however, that the scale of the program is worthy of praise, and that the Brazilian government has been able to provide housing at a level unprecedented around the world, while today England finds it difficult to build new affordable housing. Her critique does not focus on the program itself, but on how it is being implemented.

The result, says the researcher, is that housing policy is attached to the need for large and constant volumes of investment—and suffers in times of budget cuts, as in the current situation.

But the question remains: is a home not important for people who have never owned property? Would the alternative be for them to have to pay rent forever?

“I’m not saying it’s not important, of course it is. But every society has a different attitude about it. Some value ownership above renting, but that’s not a rule. In Germany, the system of rents is very standardized and there is no stigma: if you do not have a house, you do not have less value as an adult. The way the housing market operates there allows you to have a good property for life by renting. Of course it is a different world, but it is a big cultural question, with direct impacts on how policies are created and implemented. ”

BBC Brasil reached out to the Ministry of Cities and forwarded the LSE research considerations for comment but has not received a reply as of the publication of this report.