The Rio that bid for the 2016 Olympics and then reveled in its 2009 campaign victory was not shy of dreaming big. Among other commitments, the city planned to transform city-wide security, upgrade favelas, reform the broken transportation system, and do all of this sustainably with an eye towards mitigating climate change. Even a few years before the Olympics itself, these efforts began eliciting a series of awards and recognition from global networks, institutions, companies, and think-tanks.

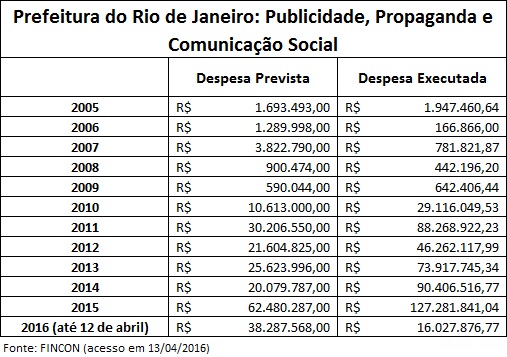

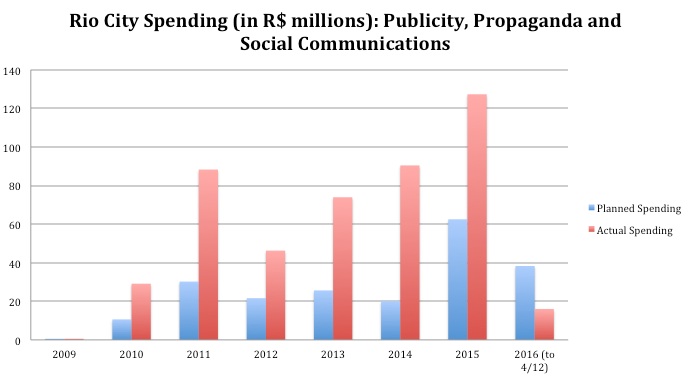

In the same pre-Olympic period the city’s marketing budget underwent dramatic growth. According to the municipal FINCON data system, from 2006 to 2009 the City of Rio spent between R$100,000 and R$800,000 per year on “publicity, propaganda and social communication.” Mayor Eduardo Paes assumed office in 2009. After being awarded the Olympics in late 2009, spending rose to R$29 million in 2010 and had grown to R$127 million for the year by 2015.

Perhaps it is the City’s marketing team that should win an award, because much of the recognition given to Rio policies and projects seemed to take the government’s narrative at face value, demonstrating poor understanding of realities on the ground. For many residents, the popular local expression, “it’s for the English to see”–which has its origins in Brazil’s slave trade history–seem an apt descriptor for this moment of global attention on Rio.

Conversations with Rio residents who are living or studying the daily impacts of some of the globally-lauded policies offer an important lens into understanding the awards and recognitions received by this Olympic City.

The World Bank Commends Pacification in Complexo do Alemão

In March 2013 the World Bank published a feature story about Complexo do Alemão in Rio’s North Zone, describing the immense progress brought about by the Pacifying Police Units (UPPs; translated by the World Bank as “peace-keeping” police force). “After struggling with violence for 30 years,” the article says, “Complexo do Alemão is now a model community.” Done and dusted, problem solved! Sadly, this claim demonstrates the level of contextual understanding we now associate with US President George W. Bush’s 2003 “Mission Accomplished” speech on the Iraq War.

From the installations of UPPs in Alemão in 2012 to the March 2013 World Bank article, police killings like those in Fazendinha and Nova Brasília triggered outrage and protests by community members while police were among the victims too. Even high-ranking police have since admitted the policy’s failure in Alemão.

The World Bank claimed UPPs mean “residents are able to move about the neighborhood.” But activist Thainã de Medeiros of the community’s media collective, Coletivo Papo Reto, argues “one of the main changes was precisely that [after pacification] we couldn’t move freely, that we couldn’t hold our celebrations freely,” pointing to the bullets and flash bombs that police used on residents during recent carnival celebrations.

In addition to peace, the World Bank praised the positive impacts of the cable car on mobility. Coletivo Papo Reto media activist Raull Santiago admits that “for a minority who live at the top of the favela, it’s really useful,” but maintains that “for a big majority, it’s not.” Thainã agrees, saying moto-taxis and kombi vans remain the most efficient means of transport; the cable cars aren’t accessible for people with mobility limitations and the system is often suspended, due to shootings or (supposed) maintenance.

For Raull, the cable car was developed for its “strategic” value “because it can be seen from various major points of the city.” Raull also highlights the waste of the large rooms that make up each cable car station. He explained:

“In Alemão we have various projects and none, I said NONE, were able to use these spaces for their activities… We were never able to get authorization to use this space, built with public money.”

The World Bank also highlighted UPP Social, a “World Bank-supported initiative” to deliver improved education and health alongside the police. While the new Emergency Care Unit (UPA) provides important services, residents RioOnWatch spoke to did not know Alemão had any of the “Schools of Tomorrow” lauded by the World Bank. (As of April 22, 2016, the schools’ official website contained broken links and had not been updated since 2013.) On the topic of UPPs impacting education, however, Raull points to the Caic Theophilo da Souza Pinto school in Nova Brasília, which “had a gigantic fall in student numbers after a UPP base was installed in the school and the area was the site of intense shooting.”

Complexo do Alemão artist-activist Mariluce Mariá de Souza argues that “from 2012 to today, [UPP Social] has not existed” in Alemão, echoing observations from across Rio’s favelas. She speaks positively about individuals working for UPP Social but adds that the program as it was marketed is “fiction,” which is a shame because in the beginning it was “a serious effort that could have improved social conditions in the community.”

Raull, on the other hand, says UPP Social was flawed from the start because “the police can’t mediate a conflict of which they are a part.” He invites the World Bank to Alemão to visit with a resident who “would show the reality.” For Thainã, another fundamental issue is the lack of real participation of residents in decision-making:

“We’re always ‘heard,’ the result of which are bizarre projects in which the government, when asked, says ‘we did this because we heard you.’ We speak, but we are not understood… They hear we need mobility, but they don’t hear that the cable car is not mobility. They hear we need health, but the UPA is not health—sanitation and leisure are health! We ask for peace, but the police with rifles and tanks is not peace! To be in the street at whatever hour I like without hearing gunshots is peace.”

C40 Awards Rio ‘City Climate Leadership Award’ for Morar Carioca in Babilônia

Rio’s Morar Carioca program was launched in 2010 with the goal of upgrading all the city’s favelas by 2020–upgrading means bringing in all the missing services these communities are entitled to, and that would bring them up to municipal standard. Heavily marketed as a key component of the Rio 2016 Olympics’ social legacy, the program won the 2013 City Climate Leadership Award for “Sustainable Communities” from the C40 network of cities. C40’s materials explained that “this priority of the Rio de Janeiro city government” had a goal “to resettle all those living under risky conditions” by 2016, aiming “to keep people within their own communities.” C40 also highlighted the side-by-side communities of Babilônia and Chapéu-Mangueira in the South Zone as implied successes of the green sustainability initiative.

Now in 2016, however, Babilônia and Chapéu-Mangueira are models of Morar Carioca’s abandonment. In 2010 the City drew maps marking residents of areas at high-risk for landslides for relocation within the community. A few of those residents were removed but many others remain. André Constantine, president of Babilônia’s Neighborhood Association, says “no improvement was made to minimize the risks due to heavy rains.” In the context of this identified urgent need, investment in (limited) solar panels and green architecture had value but also signaled a disregard for community priorities.

Not only have residents in risk areas not yet been resettled as promised, but the City recently informed them they will be moved to Santa Cruz, some 65 kilometers away in the West Zone, a total about-turn on the original promise of local resettlement heralded by C40. As of July 2015, city data showed 77,206 people had been removed in Rio since 2009; the suggestion that keeping people in their original communities was a priority is incompatible with the fact that over half of the recipients of Minha Casa Minha Vida public housing–the vast majority of which is two hours away in the city’s extreme West Zone–have been evictees.

Although community participation was a pillar of Morar Carioca, André explains that the City never presented a full project plan, with a timeline and budget, for Babilônia; nor have City officials officially informed the community what everyone already appears to know—that further works have been indefinitely suspended. Still, Babilônia and Chapéu-Mangueira received more than most of Rio’s favelas, which never saw any Morar Carioca projects implemented.

In response to the C40 award and recognition Morar Carioca has received over the years, André states: “This project is an embarrassment. And to win these prizes, it’s even more embarrassing.” Recognizing that projects which emphasize the environment and sustainability “get a lot of visibility,” he concludes that a major problem in Rio “is that everything is done ‘for the English to see,’ and things don’t work in reality.”

Marcia Sales, a resident who is still waiting for the Morar Carioca housing promised to her six years ago, concludes that it would be good if the people who gave the award “could come [here], because what Morar Carioca is, how Morar Carioca functions, is truly different from what is presented.”

Mariana Cavalcanti, an anthropologist, worked with an architecture firm contracted to design and coordinate Morar Carioca implementation in eight West Zone favelas, before the city suddenly canceled the firm’s contract. She reflects: “It seems, at minimum, irresponsible to give an award to a failure like Morar Carioca.” The award shows the power of “enough beautiful models, plans, and renderings of hyper-real spectacles that the City loves to use” to create “a vicious cycle” in which “the award helps the City prepare more glorious press releases about its big accomplishments.”

ITDP Awards Rio its ‘Sustainable Transport Award’ for the BRT

In January 2015 the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP) awarded Rio with the Sustainable Transport Award, a prize given annually to “innovative transportation strategies that protect the environment and improve safety, while enhancing transport efficiency for all users.” The Sustainable Transport Award Committee emphasized Rio’s Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system and the city’s “on track” progress “to achieve the goals of its mobility plan by 2016.”

As far as schedule goes, two of the four BRT lines, the metro expansion, and the VLT light rail system have all missed their deadlines for completion.

Investment into BRT and bus systems in general reflects an important focus on reducing car traffic by improving public transportation. ITDP’s 2013 impact analysis on the first BRT line showed significant emissions reductions. However, geographer Christopher Gaffney has argued that the BRT lines, centered on Olympic sites and Barra da Tijuca, fail to address the city’s most urgent transport needs. Transport Studies scholar Rafael Pereira cautions that studies are still in early stages but says: “From the point of view of social participation and the impact these investments have had on local communities, various studies have shown that the result is more negative than positive.”

Some whole communities were cleared to make way for the construction of BRT lines but effects like housing and business displacements are not captured in the ITDP’s impact analysis. In Cascadura the Transcarioca BRT line meant four bus lines with endpoints in Cascadura were cut. Businesses that had formed around a key bus depot suddenly struggled as commuters were redirected elsewhere. Just a couple of months later, changes to train services meant fewer trains stopped at the Cascadura station and more commuters had to make transfers on their way to work or school.

Now in 2016, Cascadura community leader Jose Fernando Silva believes that “if [the changes] had been well planned, it would have been really good.” However, he adds implementation was poorly executed, such that the overall impact on the area is still “not positive,” with “no clear schedule” for buses which, when they arrive, are often “very crowded.”

Like in Cascadura, a process of “rationalization” of buses across the city, in part to stimulate demand for new BRT options, and also widely understood as an attempt to reduce the flow of low-income residents to wealthy areas, has for the most part meant elimination or cuts of existing lines. Even in the regions the BRTs are expected to serve best, like Barra da Tijuca, these changes have caused confusion and immense frustration. Five bus lines were cut following the opening of the Transoeste BRT line and ten more were cut in response to the Transcarioca BRT. Locals complain of fewer buses on the remaining lines, unbearably crowded buses, added transfers to formerly direct routes, and the overall lack of information and communication about changes. According to an April 2016 article, Praça Seca Neighborhood Association president Alexandre Fiani says not one of the six bus lines which used to run directly by the Curupati hospital still passes by the hospital doors.

Then there are the complaints with the BRT itself. Fiani says “it’s not possible for an elderly person, a pregnant woman, or a person with disabilities to use the BRT because of the overcrowding.” One commuter called the wait times between BRT and the connecting buses “enormous.” Student and Recreio resident Luiza Lima called the BRT “dangerous and very crowded.” In 2013 the ITDP surveyed Transoeste passengers and found overall positive perceptions of changes, but warned even then that existing overcrowding and waiting times might only get worse as demand increased.

Blogger Julia Michaels cautions that we don’t know “how much the complaining is due to normal resistance to change and how much to real problems.” However, in an excellent overview of the current “chaos” of transport she highlights one indisputable problem: “Almost no one understands what Rio de Janeiro’s ‘bus rationalization’ is about. Almost everyone is at its mercy.” She quotes the Rio state Attorney General’s office, which has denounced rationalization on the basis that “without correct methodology (‘an origin-destination study’), public consultation, a positive user cost-benefit ratio and efficiency monitoring, what we will have is constant consumer indignation and continuous system instability.”

Without that data, it’s hard to mount a thorough case against the city’s recent transportation changes, but it’s equally difficult to make a clear case for its benefits.

Jose from Cascadura questions whether the people behind Rio’s Sustainable Transport Award could truly understand the impacts of recent changes either. When asked what he thinks of the award, he responded: “I really hate it… They know don’t know our reality, they didn’t speak with us.” He invites them to “visit in person” and to experience, day after day, what it’s like to navigate Rio’s transportation.

C40 Elects Eduardo Paes and Rio as Climate Change and Resilience Leaders

Ahead of the momentous Rio+20 conference held in Rio in 2012, a publication produced by Brazilian municipal Environment Secretaries asserted: “The city of Rio de Janeiro has been at the forefront on the issue of climatic change.” Shortly after the C40 recognized Morar Carioca as a sustainability program in 2013, Mayor Eduardo Paes was elected the new chair of the network—“the world’s leading climate action organization.” In May 2014, he was appointed a member of the Global Commission on Economy and Climate, which, according to City materials, is “integrated by 21 leaders who distinguished themselves” in this area.

When asked by RioOnWatch about recognitions for the mayor’s leadership to tackle climate change, biologist Mario Moscatelli responded: “There must be some mistake.”

The specifics of Rio’s disastrous sewerage and sanitation systems have been well-covered ahead of the Olympics—in part thanks to Moscatelli’s dedicated documentation—so this article will focus more broadly on climate change preparation and the bandied-about term “resilience.”

Rio is a participating city in the 100 Resilient Cities program, funded by the Rockefeller Foundation. The program defines urban resilience as cities’ capacities to “survive, adapt, and grow no matter what kind of chronic stresses and acute shocks they experience.” Participation in the program itself is not a claim of success, but rather a signal of claimed commitment to resilience. (It also signals a city’s interest in publicizing that commitment to a global audience.) In launching the “Resilient Rio” program in January 2015, Paes emphasized projects like the macrodrainage of Praça da Bandeira (an area prone to severe floods), an alarm system for risk areas, and the stabilization of precarious slopes around the city.

Raul Pinho, an engineer and former director of the sanitation institute Trata Brasil, does not believe Rio’s approach to sanitation can bring about resilience: “In general our political leaders only worry about short term actions that bring political results during an administration, which does not align itself with depollution programs for the Guanabara Bay and Rio’s beaches, and much less with actions to combat climate change.” He says Rio “does not have a long-term policy and hides behind the inefficiency of CEDAE (water and sewerage utility) to justify the continued delays and failures to deliver fantastical goals.”

A biologist involved in sustainability initiatives in Rocinha, Gabriel Voto also says Rio lacks a long-term approach. Voto says macrodrainage projects, alarm systems and slope containment works “are palliative. They’re important in the short-run but the root causes are not being addressed.”

This mirrors a major critique of the IBM-designed Rio Operations Center (COR), which has garnered Rio international marketing, attention, awards, and praise for its “Smart City” efforts, often in the context of facilitating resilience. Data collection and well-integrated communication on advanced technology platforms have transformative potential, but the presence of those technologies does not guarantee quality management and project implementation. A forthcoming article by geographer Christopher Gaffney and this author argues the “Smart City” narrative in Rio is oversimplified and thus overstates the COR’s potential, whereas in reality these projects are “not capable of addressing the most pressing needs of cities with chronic deficits in urban infrastructure and an absence of robust civil society institutions.”

Landslide risk is one area where data-collection alone definitely doesn’t equate to solutions. Voto reports that in Laboriaux one wall was built to contain the Gávea slope, but nothing was done to address the precarious hill on the Rocinha side “where high-risk housing is located.” Laboriaux joins Babilônia and Pica-Pau as yet another example of how that supposed City priority to relocate all favela residents living in high-risk situations within their own communities by 2016 has been abandoned.

Voto warns those who might consider Eduardo Paes and Rio to be leaders in climate change preparations that “many of the data passed to international organizations are not credible.” For Moscatelli, the reality is in plain sight: for the last 20 years he has flown frequently over Rio to survey the landscape below and “only sees things getting worse” through the “contamination of all the city’s rivers and the suppression of vegetation,” as just two examples. He concludes: “Probably the city that received praise must have been another city… in another dimension.”

Conclusion

One common theme that emerges from these four cases is that awards and praise appear to have been given for ideas and intentions rather than implementation. On paper, the UPPs were bold and Morar Carioca was beautiful. Rio’s transport system desperately needed change and substantial changes arrived. The city projected to be the Latin American city most severely impacted by climate change has residents and infrastructure that are terrifyingly vulnerable to natural disasters, and Eduardo Paes’ administration wants to be seen as playing an important role in tackling this vulnerability.

But there is a stark mismatch between how these projects are packaged in marketing materials (by both the City and the international actors who praise them), and how people who live the day-to-day impacts of these policies experience them on the ground. It’s not that they were good in theory and bad in practice—there will at times be some supporters whose lives have been transformed for the better. (Although Morar Carioca does stand out for being great in theory and barely existent in practice.) It’s that they are dangerously simplified in marketing and award materials, beyond recognition from the tangled, slow-changing, and controversial reality.

This simplification is dangerous because it justifies the continuation of poor policies, undermines evaluation and accountability, diverts resources from other policies, and favors politicians who are better at marketing than bringing about positive change. Moreover, it overlooks the participation and even basic feedback of the people most affected in favor of courting “global,” “expert,” “official” but often downright clueless praise. The colonial legacy of “for the English to see” continues.

Unfortunately, the Olympic Games also benefit from poorly grounded recognition. In January the company SGS bestowed the rather opaque “ISO 20121 certification” on the Rio 2016 Organizing Committee, for organizing an event that will “leave a positive economic, environmental and social legacy, with minimum waste, energy consumption, or strain on local communities.” The Rio 2016 news article offers zero evidence to justify the award.

Another key theme that emerges from all four cases are the open invitations laid out by Rio residents for any prospective judges of awards: COME VISIT. In each case, the invitation surfaced spontaneously when we interviewed people in the areas contemplated by the award in question. Come visit and talk to the real experts on these Olympic City transformations. Without that, you are just the gullible targets of a well-polished, and very well-funded, marketing machine.