![Asa Branca vs Ilha Pura [Ilha Pura image from Vice] Asa Branca vs Ilha Pura [Ilha Pura image from Vice]](https://rioonwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Asa-Branca-vs-Ilha-Pura-2-620x264.jpg)

The Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro are almost upon us, yet the city’s lack of preparedness continues to provide international media with an endless feed of concerning stories. The most recent infrastructure debacle over poorly constructed rooms in the Olympic Village has resulted in the Australian Olympic Committee deeming the village inadequate and “uninhabitable” due to safety and health concerns made apparent in their inspection.

This is incredibly problematic, in part because the Village made history as the first development in Brazil to receive the Green Building Council’s LEED for Neighborhood Development (LEED-ND) certification. The certification was awarded for the Village’s supposedly sustainably planned post-Olympic transition into an elite neighborhood named Ilha Pura, or “Pure Island,” located in the upscale neighborhood of Barra da Tijuca. This certification holds weight on a global scale and is meant to be a yardstick for sustainability and green building, and yet Ilha Pura has more than missed the mark. What is especially interesting and ironic, however, is that recent analysis by the authors of this article finds one of Rio’s nearby favelas scores 28% higher than the Olympic Village on the same LEED rating tool for green neighborhoods.

This striking result gets to a core issue of the New Urban Agenda to be debated at the United Nations’ Habitat III conference later this year: how to create sustainable human settlements for all. An estimated one billion people live in informal communities worldwide, and that number is growing rapidly.

Some of that growth is happening just a short walk from the 2016 Olympic Park in a small favela called Asa Branca. While the world celebrates the Olympics, Asa Branca will celebrate 35 years of struggle and endurance in Rio’s West Zone. Favelas are often stereotyped as chaotic and hazardous liabilities. But a closer examination reveals considerable merit in the organic and responsive environments built by residents. Compact, mixed-use buildings and pedestrian-oriented circulation networks engender the kind of vibrant, street-level cultural life and low carbon footprint that are hallmarks of green urbanism.

The concept of unplanned communities as models of sustainability emerged after the 1996 Habitat II agenda called for adequate shelter and sustainable settlements for all. Practitioners and urban scholars like John Turner, author of Housing by People, Theresa Williamson, executive director of Catalytic Communities, and Justin McGuirk, author of Radical Cities, have recognized that so-called “slums” are not deformities in the urban fabric, but are integral and important contributors to sustainability. These and other researchers see the mix of physical qualities, social vitality, and economic resourcefulness in communities like favelas that can produce transformative neighborhoods. As McGuirk asks in Radical Cities, “When will we come to terms with the fact that favelas are not a problem of urbanity, but the solution?”

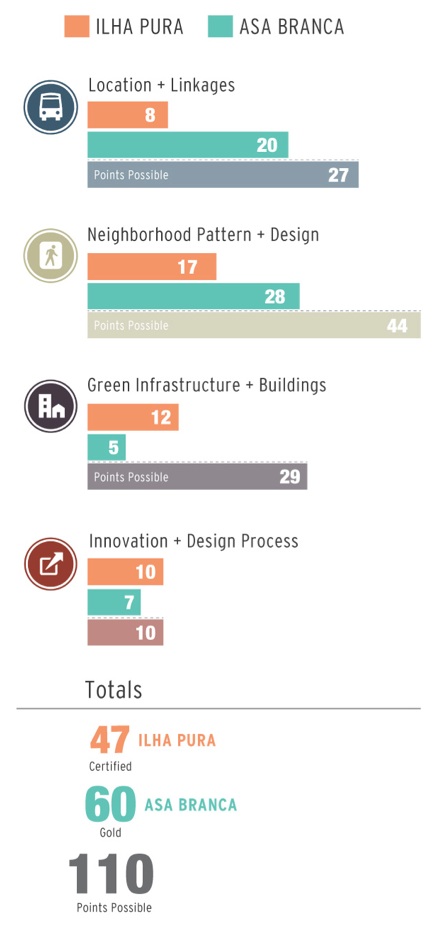

To illustrate this point, we applied the LEED for Neighborhood Development rating system to Asa Branca. LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) is a family of sustainability rating tools owned and trademarked by the U.S. Green Building Council, including LEED for Neighborhood Development (LEED ND). To judge sustainability, LEED ND combines the principles and practices of smart growth, new urbanism, and green construction into 44 measures worth a total of 110 points.

For a baseline of formal urbanism, we selected the LEED ND certified 2016 Olympic Village. Situated on 180 acres, Ilha Pura contains 3,604 new apartment dwellings for about 8,000 residents in 31 buildings averaging 18 stories in height, with supporting commercial and recreation amenities. On the LEED neighborhood sustainability scale, Ilha Pura scored 47 points and earned an official LEED ND Certification. 40 is the minimum number of points needed to reach a “Certified” ranking (40-49 points), with higher scores meriting Silver, Gold, or Platinum rankings.

A half mile north of Ilha Pura, Asa Branca also has 8,000 residents, but they live in 1,800 dwellings in single and multi-family buildings that range up to four stories in height, on a 27-acre site. 98 small businesses in the favela serve residents’ daily needs. Using the LEED ND yardstick, Asa Branca scores a Gold ranking with 60 points, an impressive 28% higher than Ilha Pura.

A half mile north of Ilha Pura, Asa Branca also has 8,000 residents, but they live in 1,800 dwellings in single and multi-family buildings that range up to four stories in height, on a 27-acre site. 98 small businesses in the favela serve residents’ daily needs. Using the LEED ND yardstick, Asa Branca scores a Gold ranking with 60 points, an impressive 28% higher than Ilha Pura.

How does informal urbanism so markedly outperform state-of-the-art formality? The ND scorecard reveals that Asa Branca can’t match Ilha Pura in the green construction and innovation categories because of the latter’s advantages in financing those premium practices. But Asa Branca has nearly double the scores of Ilha Pura when location and neighborhood quality are tallied, including these highlights:

- Affordable housing. Ilha Pura didn’t attempt affordable housing points, but Asa Branca earns the maximum with more than 25% of its homes priced affordably by Rio de Janeiro standards. And the housing is close to surrounding job sites, creating a point-worthy jobs/housing balance for the vicinity.

- Connectivity. Asa Branca’s fine-grained circulation network gives it a highly superior internal connectivity of 875 intersections per square mile, enough to earn an exemplary performance point; and its adjacent, high-frequency transit service earns maximum location efficiency points while connecting residents to regional jobs.

- Compactness and completeness. 100% of Asa Branca’s circulation network are pedestrian paths or woonerfs (where pedestrians have priority over vehicles), all fronted by zero-setback buildings that activate street life with 98 ground-level shops (and jobs) that are a brief walk or bike ride from anywhere in the neighborhood.

- Social equity and collaborative governance. The Asa Branca Neighborhood Association qualifies for the social equity and outreach credits as a grassroots organization working to create a fairer, healthier, and more prosperous neighborhood.

The Asa Branca results are not an official LEED ND rating like the Ilha Pura certification, but they should prove useful on several levels:

- The Asa Branca Neighborhood Association, which assisted the ND study, can use the results to strengthen collaboration and investment by local government, and those investments can more effectively focus on needs identified in the ND rating, e.g. outdoor civic space, rainwater management.

- The results should spur assessment of other favelas to see if favorable scores persist in a variety of settings, if patterns emerge, and what sustainability attributes are strongest and weakest. While the weaknesses must be identified in order to be addressed, the strengths must equally be identified in order to make sure they are preserved. This also highlights a related, serious global problem: the absence of basic data on favelas, which is urgently needed for correctly understanding strengths and weaknesses, and designing effective responses.

- In fashioning the New Urban Agenda and its “operational enablers,” Habitat III participants can reconceptualize favelas to be essential contributors to sustainable urbanism. The small environmental footprint, social vitality, and economic resourcefulness of informal settlements justify their rightful and productive place in the urban fabric.

Asa Branca won’t host Olympic athletes this summer, but it does appear capable of winning Gold using a global standard of neighborhood sustainability. This doesn’t diminish the serious problems that Asa Branca faces, nor do the results necessarily represent all of Rio’s diverse favelas [further research is necessary to gauge this]. Nonetheless, Asa Branca’s bustling street life and close-knit residents are convincing evidence of the strengths gained from an organic and responsive built environment. The world can take a lesson from this informal gold medalist—that embracing and leveraging the vigor and potency of favelas and informal communities across the world is critical to achieving sustainable urbanism.

Eliot Allen, LEED AP-ND, is a sustainability rating specialist at Transformative Tools, and creator of the LEED UP method of favela upgrading. Julia Jones is an international relations student at Syracuse University, and former intern at Catalytic Communities.