When Eunice do Nascimento Rosa, 56, came home from work some weeks ago at night, she almost stepped on a snake lying on the floor of her home. She only managed to see the snake because the lights of her cars were still on. Otherwise, when the sun goes down, Eunice lives in the dark. For well over a year, Eunice and ten other families in the Hípica community in the Tijuca Forest National Park having been living without electricity.

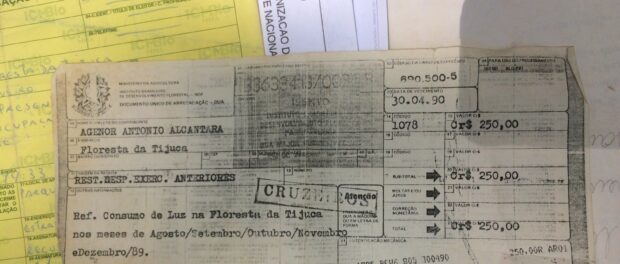

No buses come here, the phone reception is weak and it’s an hour hike through the forest to get to the nearest supermarket. But none of that really matters to the families living here–it is the electricity they care about. In the past they had an electricity supply; Luci Rosa de Alcomtona, 59, has a huge envelope where she keeps all the old bills in orderly manner along with other official correspondence.

Her father gave her the documents, saying: “Here are the weapons, now you’ve got to fight.” He passed away three years ago. Luci believes it was not the cancer that finally killed him. “It was the lack of electricity,” she says. He went to the park administration three times to dispute the situation, but they would not see him. At night, he could not sleep. Luci pulls out a medical report of her resistance envelope. “He should not be put in stressful situations and he needs a refrigerator at home for his medicine. If there is none, there is an increased risk of death,” she reads out.

Luci is not the only park inhabitant who blames the park administration for the poor health condition of a close relative. Maria Haydée Alves da Silva Teruz, 58, lives together with her mother, five nieces, her nephew, his wife and their children in a dilapidated 19th century building which once belonged to the Viscount of Bom Retiro.

The wooden ceiling beams bend; there is a big stone fireplace, broken antique tiles and a rug that seems to have lost its color along the centuries. In a small dark chamber, wrapped in a thick cloth, lies Haydée’s mother. Three years ago, she fell on the floor in the dark and now she cannot move anymore.

She suffers from Alzheimers and depression, due to the lack of light, her daughter says. Haydée is the only person in her community that has a generator, although she cannot really afford the gasoline. “I need warm water to bath my mother and light at night to change her diapers. How do you do that in the dark?” she asks.

Yet the electricity supply they long for is there. Three brand new power distributors are within sight in front of the house, around 20 meters away.

But they are not connected to the houses. This is not a coincidence or sloppiness. The Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation, responsible for the protection of the park, wants Haydée and her neighbors to leave. According to national law, living within a nature conservation area is prohibited. But when the Tijuca Forest National Park was officially created in 1961, Haydée, Eunice and Luci already lived there. Their families originally came to live in the park because the public authorities asked them to: their parents worked in the park to take care of it. They helped build the roads and paths, planted trees, and helped visitors.

Now, residents have already received various written requests to leave the park, but without any offer of alternative housing or compensation. They would consider leaving, but don’t want to be forced to go far away in the periphery, as happened with one of their former neighbors who now lives in a favela in Jacarepaguá. The remaining families are not even allowed to fix up their houses. Slowly, they are turning into ruins in the middle of the jungle.

Residents view the cutting off of the energy supply as a tactic to pressure them to leave. “It is social segregation,” says Otávio Barros, president of the nearby Vale Encantado Cooperative and supporter of the families in their struggle. “In the 21st century having electricity is a human right. It is about dignity.”

For decades, residents paid their monthly bills in the bank. But one day, the bank refused to take the money. Then the cables were disconnected from the community. Haydée and her neighbors took legal action, but they haven’t heard anything from the courts for six months.

“We feel like a plaything. No one takes responsibility and no one offers any solution. What shall we do?” asks Luci. They fear their case will be ignored and nothing will ever happen. In the Tijuca Forest, home to the world famous Corcovado and Christ the Redeemer statue, residents are left in the dark.