On Sunday, October 23, the second National Forum of Citizenship and Poverty took place, promoted by the NGO TETO in various Brazilian cities where it operates. In Rio de Janeiro, the event occurred at the Governor Leonel de Moura Brizola Municipal Library in the center of Duque de Caxias, a municipality in the greater metropolitan region of Rio de Janeiro.

In the second edition, the event sought to fuse debate, music and art to further a discussion about the right to the city and the relationship with poverty and inequality in Brazil, involving the NGO’s volunteers, favela residents where the NGO operates and guests from partner organizations.

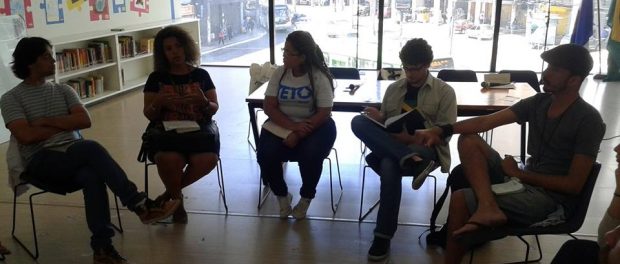

The first panel of the event, National Political Crisis and Setbacks of Rights in Favelas, was transformed into a roundtable conversation and discussed the current federal political scene and its effects on favelas. Flavia Mendonça, local articulator and educator in the project Aluno Presente, spoke about how the guidelines and operation of neoliberal institutions affect the favelas. At a time of political and economic crisis, rights are more relativized: “The resident only sees the state in the form of the police. It is difficult to make it so that they don’t see their rights as charity or meritocracy, in terms of ‘I need more’ or ‘I deserve more.'”

Guilherme Pimental, from the Meu Rio network, spoke about the gears that a national political crisis sets in motion, taking the crisis out of the political arena and going to the police. This is exemplified, according to him, by the removal of political debate and greater importance given instead to the arrest of Eduardo Cunha and even Marcelo Crivella, which ends up shielding political decisions that are being made, such as austerity constitutional amendment PEC 241, and that aren’t debated. On the local scale, the shift also ends up removing the debate about the city.

He also pointed out that at the moment there is a demand for order that is fueled by great fears sown by judicial institutions, the police and the mainstream media. The first is a fear of corruption, which creates the problem of redeeming solutions such as the documents on ten measures against corruption which, if approved, looks to reduce defense resources and increase those for prosecution. This is a permanent solution to a temporary fear, which will culminate in the hardening of the penal system and ultimately will contribute to the biggest detention of the main targets of the criminal policy: poor black youth. In the case of the fear of economic crisis, there’s the PEC 241 which justifies social cuts to reduce public spending for twenty years, which will again most affect poor black favela youth.

Thainã de Medeiros, resident of Complexo do Alemão and activist with Coletivo Papo Reto and other networks, also stressed that fear and a crisis promote exceptionality. “It is based on the fear of the mass beach robberies that you prohibit and search the buses going from the North Zone to the South Zone. It is based on the fear of drug trafficking that you justify the military’s entrance into a favela and the establishment of permanent occupation, or that you justify entering a resident’s home to exchange gunfire,” he said.

He commented on the perception that a favela does not know how to organize itself and that this disorder benefits the trafficker: “In the 2013 protests people learned to jump over the turnstiles; in the favela people have been jumping the turnstiles for a long time. In the favelas there are resistances organizing themselves and looking for transportation solutions, which aren’t just jumping turnstiles. It’s inventing the kombi, inventing the moto-taxi, inventing ways to survive in a city that does not want us to survive.”

Fabiana Silva, debate mediator, educator and resident of the Parque das Missões favela–one of the favelas in Duque de Caxias in which the NGO TETO operates–stated: “In Parque das Missões there is no bus but there is a lotada which is a tour bus acting as a taxi. With this, the resident is able to resolve their financial problems and help others. We don’t have a health center, but there’s a resident who is getting a degree in nursing who goes to people’s houses with first aid and to give vaccinations, bypassing the system.” Dona Ilma, resident of the favela Parque das Missões and local leader, agreed: “If the people didn’t organize themselves, the police would come, but public policies don’t enter.”

Thainã said that was also one of the reasons why he doesn’t participate in certain meetings and broader demonstrations: what people are claiming in them has already been a claim of the favela for a long time. “I will not go to the streets to protest to take a bullet, because I already have to leave my house under gunfire and go back home under gunfire. If it means taking a bullet, I’d rather stay here,” he says.

Another motive is that he doesn’t want to be used as political capital to legitimize policies and institutions like the police, who would benefit by being able to say that they are talking with the favela. And that conversation is frequently fruitless, according to Thainã: “When I talk with the police saying I want peace, I mean that I don’t want the UPP or the tanks, but they take it to mean that I want more police. What I want is to build together, I want to be the agent of my own actions.” Dona Ilma expressed similar concerns: “Between the police and the criminal, sometimes we prefer the criminal because we can talk with him, but the police don’t give an opportunity.”

Fabiana and Thainã commented on the lack of penetration of left-wing politics in the favela. “Not even the left sees the favela as an organized place, with the potential to do grassroots organizing there,” says Thainã. Fabiana added: “Those on the edge don’t know of the left or the right, but they know the price of rice, they know the police enter that space and take away their rights, they know when they don’t have access to quality health care.”

Thainã wrapped up trying to respond to the issue of what leads someone to go into trafficking: “The discourse about there being no alternative is not the best… It doesn’t have a right answer. But in general, he goes into it because he’s an idiot–and there he could also enter the police force–or he goes into it to make money. And money acts as a confirmation of subjectivity and self-esteem, to be able to look someone in the eye and not lower one’s head, to be respected, to be seen as the being that he is: a powerful guy, a guy who makes things, who contributes to society.” Wagner Bayão, an art teacher in the public education system, spoke about the key role of school to insert an individual into society, an individual who has his subjectivity constantly denied.

At lunchtime, there was a cultural intervention by the experimental theater group made up of CIEP 350 students, a state school located in Parque das Missões, coordinated by professor Wagner. The piece presented, O Farso do Boi ou O Desejo e Catirina (The Farce of the Ox or Desire and Catirina), written by Adriano Barroso from Paraná, brought typical elements of Brazilian culture like the Enchanted, a cult figure in the religious practice of Encantaria of indigenous and Afro-Brazilian origin, and enthralled and moved those present.

The second discussion on municipal elections and social participation brought together different perspectives on how the vote for city government and city council members can impact or not the favelas in the metropolitan region, how residents organize themselves to claim rights and the impact of the New Urban Agenda, defined last month at the United Nations Habitat III conference, on the dynamics of housing and Rio de Janeiro’s government.

Fernanda Pernasetti, architect and PhD candidate at the Rio de Janeiro Federal University’s Urban Planning Institute (IPPUR/UFRJ), spoke about the commitments made in Quito in the New Urban Agenda and the need to develop more participatory cities. Leandro Vieira, political scientist and sociology teacher in the public school network, stressed that it is important to speak of the electorate to speak of the election: “People don’t like to talk about politics, and that’s not their fault. It is important to have a substantial democracy instead of having a formal democracy, a democracy that will go beyond democratic institutions.”

Egeu Laus, coordinator of the project Viajantes do Território (Territory Travelers) which aims to collaboratively map socio-economic activities in the Port Region, stressed the importance of civil society’s role in the presence of a governance vacuum. Irene Melo from the Observatório das Metrópoles (Metropolises Observatory) used the Minha Casa Minha Vida program as an example of civil society participation through Minha Casa Minha Vida-Entities, a branch of the program that allows associations and other non-profit entities build housing projects that are more aligned to their needs.

Aline, an activist and resident in the Vila Beira Mar favela, also in Duque de Caxias, underscored the growing diversity and mobilization of civil society in the form of favela residents: “I think that people are waking up, are better understanding what they want. I seek better things for where I live, I seek rights that people have and don’t know about.” One of those rights is the right to housing. The land where her family and neighbors live belongs to the Navy. She said they have to live with daily uncertainty. “They would come and say: ‘As long as we don’t need the place you can continue to live here, but when we need it, you’ll have to leave.’ But now people looked into it and they know that they have a right to the land, because my mother has been living there for over 40 years. It’s adverse possession.”

Marcele Decothe from Amnesty International Brasil and resident of Parada de Lucas says she began to be interested in public policy due to the lack of it. “They always told me that security policy meant police, meant the operations. I went to read because I wanted to know why there were two Rio de Janeiros. Why there wasn’t a public policy on health that worked. The theory exists. It doesn’t work because they don’t take blacks into the equation, they don’t contemplate people like us. We live in a crisis of representation that will only be resolved once there are black city council members, a black mayor, a black president,” she said.

For Marcele, race and poverty are inextricably linked and core issues to think about in public policy and social participation. She says it is necessary to transform a language that is academic and white and in that way racialize the debate. “It’s not only empowering blacks in the sense of giving them power, but to emancipate them, in the sense of giving them a choice,” she advocated. She sees black territories as territories excluded from the city’s projects, but affirms that the Baixada Fluminense and the favelas cannot be deposits of labor for the current mode of production that requires a black body to work.

In conclusion, Marcele provoked the audience: “How will you get a person out of the house on a Sunday to be here to talk about housing and citizenship, when he or she works from Saturday to Saturday, when he or she has never participated in decision-making?” For Aline, there is another great obstacle to participation: “Residents lose confidence. They see a project come here and then they see it disappear. They need to see something gain strength.”

The event closed at the Praça do Pacificador, where the library is located, with a performance by the group Locomotivas, to which several people passing by joined.