This is the first article in a four-part series on the social construction of favelas and the potential of favela tourism to break down negative stereotypes.

One of the key perpetrators of creating and contributing to negative stereotypes of favelas is the mainstream media. In addition to the news media, worldwide popular films such as City of God (2002), City of Men (2007), Elite Squad (2007) and Elite Squad: The Enemy Within (2010) have put stigmatizing images of favelas and their residents on screens across Brazil and around the world. In addition to favela residents being categorically stigmatized—according to categories like crime, poverty, race, unemployment—media that perpetuate these stigmas in turn strengthen territorial stigmatization: stigmatization solely based on being from the favela.

The favela as a cinematic landscape

Early twentieth century films romanticized favelas before giving way to the period of Cinema Novo in the 1950s. Cinema Novo films highlighted favelas’ social issues by using principles of Italian Neorealism: shooting on location, using non-professional actors, and touching on contemporary subjects. One of the founding fathers, Glauber Rocha, summarized this as “the aesthetics of hunger.” Despite the attempts by directors to respond to real societal issues through films, though, we still have to question if this style accurately portrays favelas.

Since the abrupt death of Cinema Novo in the 1970s, the aesthetics of hunger has transformed into the aesthetics of urban violence, in which turf wars, drug factions and favela-linked violence dominated the screen. From films portraying the social issues that favela residents themselves coped with, the films now portrayed favelas and their residents as the source of Brazil’s violence and drug trafficking issues.

Despite the focus on urban violence related to drugs, gang factions and (corrupt) police and the resulting stigmatization, some elements of broader societal issues and exclusion are visible in the four films discussed in this article.

Stigmatization through film: youngsters become gangsters

City of God tells the tale of favela City of God between the 1960s and 1980s based on the semi-autobiographical novel written by Paulo Lins under the same title. Although the book explains the historical development of the favela and gangs’ complex role in establishing social order, the film focuses on drug trafficking, turf wars and other related violence that dominates today’s mainstream media coverage of favelas. The same thing can be said about City of Men. Despite its efforts to focus on the lives of fatherless boys, the film is dominated by the use of stereotypical gangster histrionics.

City of God touches upon two criminological theories of how youth become involved in crime. The first theory suggests some criminals are born to be bad (like the psychopath Dadinho who changes his name to Zé Pequeno when he grows older), drawing on outdated theories of the ‘biological criminal.’ This idea is reflected by the film’s narrator when Dadinho kills for the first time: “He always wanted to rule City of God… That night he satisfied his thirst for blood.” The second theory states criminal behavior is influenced by the environment (places and people), as is implied when Zé forces another child to kill a toddler. Such images contribute to the stigmatization of favelas as criminogenic places, suggesting they inherently produce violence.

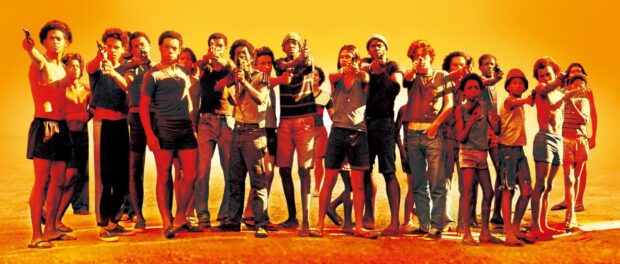

In all four films, images of black youth with guns, either using or selling marijuana or cocaine, are a repeated visual for the audience. City of God and City of Men both include favela residents that seek to remain out of the drug business, resulting in more humane story lines about those particular lives. In contrast, aside from a few shots of innocent residents in a BOPE police raid, the Elite Squad series mainly shows inhabitants involved in gangs and violence. In all four films, the image of favela residents carrying guns is more prominent than the short shots of working residents (in City of God and City of Men) or innocent bystanders (in Elite Squad).

Although adolescents with guns or walkie-talkies are present in parts of certain favelas, for audiences who only know the favela from the outside through media or film, crime becomes decontextualized. This is problematic as these films create the image that the majority of favela residents is involved in gang-related issues, whereas in reality less than 1% are involved in trafficking.

City of God’s final scene plants seeds in the viewer’s head that the worst is yet to come: it shows a group of young favela boys aged five to seven walking through the favela after they killed Zé, creating a “death list.” According to some analyses of the film, these boys grow up to form the now feared Red Command (CV), as this gang is known to have a death list. The film’s implied direct connections to reality today thus contribute to a real culture of fear among audiences.

In all four films, a belief in racial inferiority is used as justification for police handling of criminality. In City of God, a police officer suggests to his partner that they keep stolen money when they find it, justifying his idea with the question: “since when is stealing from blacks and thieves a crime?”

Due to Brazil’s colonial history—and its lack of a real break with colonialism—dominant members of Brazilian society have always marginalized African descendants and labeled them with negative stereotypes. Real correlations between class and race have created stereotypes linking Afro-Brazilians to crime, racial inferiority and poverty. This type of exclusion reduces opportunities to gain access to (adequate) social services and restricts participation in the labor market. Agatha, a tour guide born and raised in Cantagalo, sadly admits: “the government doesn’t give equal opportunities to everyone. The whiter you look, the more chances you have.”

Systemic Exclusion

Despite reinforcing some stereotypes, these movies do acknowledge some broader aspects of systemic inequality, in particular geographic isolation and economic exclusion. However, some of these acknowledgements are incomplete or misleading. More detail on each of these is given below:

Geographic isolation

In the opening scene of City of God the narrator provides insight about the history of the City of God favela accompanied by images of black Brazilians arriving by foot, carrying mattresses, suitcases, furniture and sheets filled with personal belongings:

“We came to City of God hoping to find paradise. Many families were homeless due to flooding and acts of arson in other favelas. The bigwigs in the government didn’t joke around. Homeless? Off to City of God! There was no electricity, paved streets or transportation. But for the rich and powerful our problems didn’t matter. We were too far removed from the picture postcard image of Rio de Janeiro.”

Relative to the other films, City of God includes more historical perspective. However, the previous quote is the only time the narrator criticizes the government and “the rich and powerful” this directly. Interestingly, he blames the relocations on flooding and arson, even though the governor of that time, Carlos Lacerda, is well-known for eradicating favelas in the South Zone and relocating residents to newly built public housing in City of God and other areas on Rio’s outskirts.

The same film hints at City of God’s isolation. When the neighborhood was founded by the government as an area to relocate residents evicted from central favelas, there was nothing nearby. The movie displays this by not showing the favela’s surroundings. The other films were shot primarily in highly urbanized and dense North Zone favelas that show their relative proximity to the asfalto, or ‘formal’ city. City of God’s isolation is further highlighted by a scene in the movie in which a woman is worried about a delayed bus that makes her late for work; a boy working on the bus replies: “it’s not our fault, the company runs few buses on this line.” This type of isolation of public housing is still present today, and in the run-up to the Olympic Games, the city government’s changes to bus routes made it more expensive and difficult for those living on the city’s periphery to travel to the South Zone for work or pleasure, even as evictions to new public housing on the city’s distant outskirts ramped up, repeating the mistakes of the past.

Despite the film’s implicit display of these issues, it does not directly criticize state negligence.

Economic exclusion

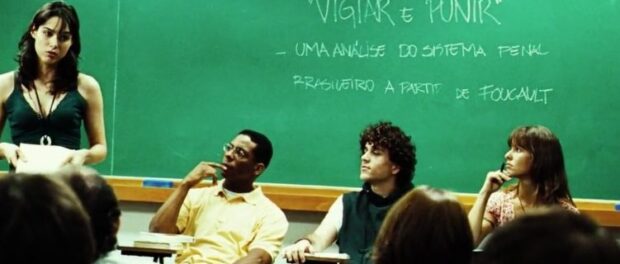

The films Elite Squad I and Elite Squad II, based on a 2006 book by anthropologist Eduardo Soares and two former BOPE captains, are a semi-fictional production that shows the daily operations of the Military Police’s Special Operations Battalion or BOPE. In the second film, university lecturer Fraga–whose character is based on the early work of human rights defender-turned socialist politician Marcelo Freixo–touches explicitly upon political exclusion in his class. Unequal opportunities and the denial of citizenship are emphasized by a presentation in which students explain the criminalization of the urban poor due to police actions in favelas.

And when Matias, a black law student and police officer walks into Fraga’s lecture, the narrator explains: “In Brazil, a poor black man doesn’t have many opportunities. But Matias didn’t care, he wanted to be a lawyer so he enrolled in Rio’s best law college.” The quotation is, however, contradictory: on the one hand he highlights unequal educational opportunities, while on the other hand, he implies it is easy to join the best law college.

As sociologist Vera Batista points out, “the fact that public elementary and high schools are free and open to everyone does not say anything about quality.” The public education system does not prepare children for public universities, Brazil’s best, as well as the private system does. Obi, the founder of tour agency Favela Brothers and a tourism university student from Rocinha, explains:

“The ones that have a private educational background take the public university spots, whereas the only option to access universities [for us] is to pay for expensive university programs because it’s easier to get into, but it’s hardly possible due to the high prices.”

As all the films show children in school uniforms, they suggest a different reality in which the government provides adequate education. By using implicit arguments of agency, favela residents can be blamed for their own lack of trying.

Furthermore, in City of God, favela residents are portrayed as caring little about schooling. Buscapé tells his brother that he only goes to school because he dislikes physical work. In City of Men the main character, Laranjinha, answers a question about school with: “great, they’re on strike, so that’s great!” This indifference does not correspond with the fact that, in real life, many favela residents care strongly about education and are intensely angered by shootouts and other impediments to their active schooling.

These movies do capture some of the discrimination and limitations present in Brazil’s labor market. In City of Men Laranjinha tells his friend Acerola: “the rich kids drive a car when they turn 18, the poor start to work.” The films also reflect another distinction between economic classes through the use of specific words for rich kids—“playboys”—and for people from the favela—“vagabundos” (vagabonds), “traficantes” (traffickers), and “bandidos” (bandits).

Class distinctions are also emphasized through the favela residents’ use of slang and clothes: flip-flops, shorts and a simple T-shirt. In City of God the children are often wearing filthy rags, often too small or torn, which risks implying favela residents are dirty either due to poverty or a lack of etiquette, despite Brazil being among the most hygiene-obsessed countries and its low-income population as committed as anyone else. Elite Squad takes this social hygiene politics further by regularly portraying the people from the favela as sweaty and minimally dressed, whereas the BOPE officers—even after a raid or during a training—still look neat and less sweaty.

Conclusion

These films reflect societal concerns about a particular enemy: drug traffickers. They shifted favela film aesthetics from utopian to dystopian aesthetics of urban violence in which the favela is quintessentially dangerous. In the case of the Elite Squad films, they shifted cinematic attention from favela residents towards forces of the state, only using the favela as a landscape of criminality and violence.

And although class paradigms exist in Brazil, the films reinforce the collective stigmatization of favela residents. By reducing the complexity of existing issues, the stereotypes are only strengthened. Therefore, the films function as an affirmation of pre-existing stigmas rather than challenging the structures that led to such systemic exclusion. The constant visual of young gang members who do not have significant character roles in the films supports the spatial disgrace of favelas.

Carla,* a Rocinha resident and tour guide, explains just how harmful stigmatizing representations of favelas can be:

“It’s the rich versus the poor, rich people think we [people from the favela] are only thieves and bad people… I’m proud to be a favelada because I don’t care what others think. But a lot of people from the favela do, it influences them! Even if they accomplish a university degree, they end up as a lawyer’s secretary or an assistant rather than a doctor… not only because of discrimination but also because they don’t believe in themselves. They believe they are less worthy because it has always been said by the media.”

Despite perhaps the critical intentions of the directors to raise awareness about societal issues, their portrayals of the favela’s connections to criminal culture means crime is decontextualized. Instead of raising awareness, this leads to a reinforcement of negative stereotypes of favela inhabitants on a global scale.

This is the first article in a four-part series on the social construction of favelas and the potential of favela tourism to break down negative stereotypes.

Phie van Rompu, M.A., graduated in Global Criminology at Utrecht University in the Netherlands. She researches state-organized crime, (de)criminalization, resistance and drug-related issues. This RioOnWatch series is based on her Masters research.

*Some names have been changed.

Full Series: Social Constructions of the Favela through Films and Tourism

Part 1: Stereotypes in Popular Films

Part 2: Glorification of War and Violence

Part 3: Favela Tourism as Resistance

Part 4: Tourist Perceptions Before and After Favela Tours