This is the fourth article in a four-part series on the social constructions of favelas and the potential of favela tourism to break down negative stereotypes.

The first two articles of this series analyzed how favela stereotypes are constructed in popular films and the third proposed a framework for community-based favela tourism to debunk stereotypes. To understand whether stereotypes are indeed challenged through community-based tours, this article focuses on tourists’ perceptions of favelas. Twenty-one tourists, primarily from Europe and North America, were interviewed before ever entering a favela and again after attending a favela tour.

Pre-tour perceptions

Following film criminologist Nicole Rafter‘s reasoning that crime films help shape our understanding of crime and the world, the genre of favela crime films thus are seen to offer the inside scoop, a window into the inaccessible but riveting world of the favela and BOPE trainings. As with prison films, the popularity of films featuring favelas can be traced to their claims of authenticity. City of God (2002) and Elite Squad (2007) each start with claims of authenticity such as “based on a true story” or “despite possible coincidences, this film is fictional.” In addition, City of God closes with photos and video of the real people and news events the fictional story was based on. In part due to such claims of authenticity, the movies form an influential source of information (and misinformation) about what goes on in favelas.

When asked what the favela is known for, every tourist interviewed prior to visiting a favela replied to the question without hesitation: “poor, uneducated, criminals, drug dealers;” “favela is just the epitome of poor and completely outside the society;” “obviously really dangerous, gangs, very poor people and the living conditions are unfortunate;” “a lot of crime is going on there.”

German architecture student Stefan* stated that the only favela news coverage in Germany was “about the violence coming in and out of the favela, drug dealers being the bosses of the favelas, the wars between gangs and the police.” UK military pilot Mark said “the only references in the UK about favelas have to do with anti-drugs operations, always violent coverage.”

However, when asked to give a more thorough description of a favela, people’s ideas were influenced by visuals from the films. English tourist Jef explained he thinks favela stereotypes are “drug trafficking and poor people.” He expanded: “Especially from watching movies like City of God, often, Afro-Brazilians [are associated with being] involved in the drugs business with guns. It influenced me massively! After watching City of God you would never want to step in there. It seems to be the most dangerous place on Earth. Perhaps the film exaggerated but it definitely contributes to how I think about the favela after already getting negative media coverage.”

Others provided descriptions of favelas as close-knit, self-made neighborhoods (as shown in City of God) with a strong sense of community. They also spoke of a social order where self-policing with severe measures is a more common solution to conflict than going to the police, an idea illustrated in Elite Squad‘s portrayal of gang brutality towards an NGO, or City of God‘s portrayal of residents’ refusal to give information to the police. Tourists imagined that education is minimal with children working from a very young age, which matches City of Men (2007) and City of God’s depiction of the young main characters already working.

A clear example of film images blurring with reality is illustrated by a remark by German tourist Anja: “It’s really just like in the film—the creaking, way too loud sound systems with echoing funk music.” Rather than saying that the film reflects reality, she frames the actual reality as a confirmation for images in films.

All the tourists’ favela descriptions included crime and gangs. Some tourists were aware that films had the potential to reinforce negative stereotypes portrayed in news coverage. As Emma from the United States said: “if a film only shows the criminals and bad stuff, it only reinforces the bad stereotypes. I think that’s why my professor let us watch the TV show City of Men (2002-2005). It’s about the boys not being involved, so it gives a more balanced view.”

The responses from Vilius, a tourist from Lithuania, offered a different angle on the relationship between films and news coverage. He explained that in Lithuania the coverage on Brazil is mainly positive, focusing on sports, tourism, and Catholicism. He suggests that Lithuanian people do not want to remember their country’s violent history so they tend to avoid negative news. Since the film City of God contradicted the mostly positive news he was exposed to, he was the only tourist interviewed who had assumed the film was a “completely fictional Hollywood story” that didn’t necessarily teach viewers anything about reality.

In contrast, it seems that in countries where news coverage about Brazil’s favelas is predominantly negative, people assume the images presented in these films are realistic.

Post-tour perceptions

After taking a community-based favela tour, the same tourists were asked to consider their definitions of favelas again. This second set of descriptions shifted from a focus on criminality and danger towards a focus on favelas’ sense of community.

After his visit to Cantagalo, Jef explained: “I think I’m surprised because I always thought they were lawless places, left behind, but it’s almost like a mini version of normal society where everything actually runs quite smoothly. I expected a tight-knit community but the community sense was stronger than I thought. While walking around, our guide knew pretty much everyone, also telling a kid off on the street because he did something… It’s more sophisticated than I imagined it to be. When you hear about favelas and see it on TV, it looks completely dilapidated, just like houses and people scraping by on whatever they can get. I didn’t imagine they’d have a proper system in place.”

Stefan participated in a tour in Rocinha and said the favela “seems relaxed, there is a strong sense of community and it feels like many know each other and that there’s lots of stuff people do together. It seems, when you walk on the streets, they have their little living room in front of their house interacting with other inhabitants, so there’s a strong relation of community in the favela.”

In addition to observations about the tight-knit community, facilities were also at the core of tourists’ new definitions. Emma pointed out that favelas “have pretty developed services, most have water and electricity, cable, Internet, the Association with all its facilities… It really debunks the idea of favelas being slums. There are parts or other favelas that are more slum-like but these are just functioning neighborhoods. Self-regulated functioning communities.”

Tourists were explicitly asked whether their perceptions had changed, and most of the tourists confirmed they had. Laura admitted to previously being poorly informed, saying the tour had “changed my perception of the favela and people living in the communities. I underestimated how many people work… My earlier perception was poor, no jobs, no chances, no food at all. My idea was that it wasn’t even working class, just like the poorer class.”

The tourists also focused on aspects of favelas that need to be improved and that differences between favelas exist as well. These remarks suggest that the tours do not glamorize or romanticize favelas but provide information reflecting ‘both sides of the coin.’ Dutch tourist Roy reflected: “I wouldn’t say they are better off than I thought at first, obviously they have more difficult conditions. But there are a lot of positives that I didn’t imagine before. Although you do know crime occurs at times I get an overall positive feeling from the people living there.”

Some of the most significant reflections were expressed by a Brazilian couple from São Paulo, two of the few Brazilians encountered on the tours studied for this research. For Flávio, “the tour changed the way we see the favelas and Brazil. One of the things that impressed us most was hearing from our guide that many people actually stay in the favela and never leave because they have everything there. It seems they are an invisible part of the city and country and none of the proposals we have in our politics today include a long-term plan for them. More than that, we could see that despite the problems and issues they have there, we could find great people, willing to help one another.”

Before and after in words

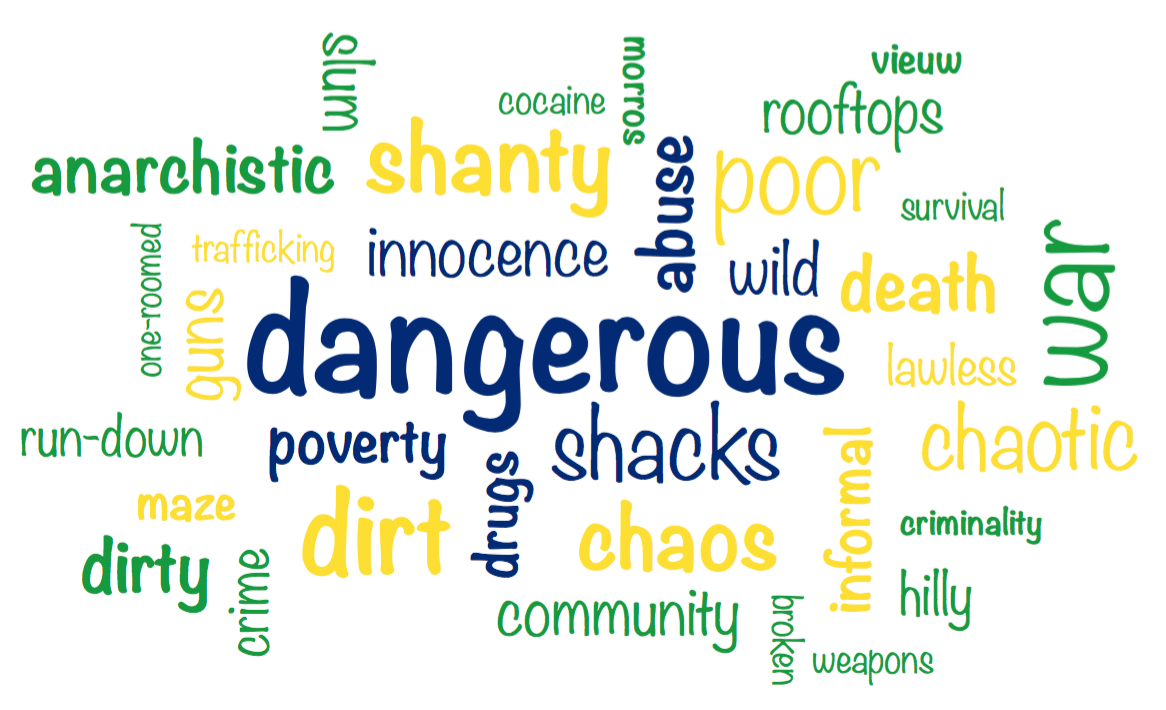

The tourists were also asked to sum up the favela in three to five words, both before they entered a favela for the first time and after a tour.

The word cloud above with their pre-tour responses shows significant differences from the word cloud below with their post-tour responses. Interestingly, although their answers about how their perceptions had changed included both negative and positive aspects of the favelas, this word exercise primarily shifted from words reflecting criminality and danger towards words that highlight positive aspects of favelas, with a few exceptions including “poverty,” “surviving,” and “primitive.”

Conclusion

For those who have never been in a favela, films can shape people’s way of thinking about these places, reinforce existing stereotypes, and cause the favela to be stigmatized on a global level. Although traditional news media play an important role in shaping perceptions held by foreigners and Brazilian residents of the asfalto (formal city), the films provide a more detailed image of the favela that people use to define their perceptions.

Community-based tours are an opportunity to deconstruct these images, especially in the minds of those who have never entered a favela before. From perceptions closely connected to news and film images, the perceptions of tourists interviewed after their tour featured more nuanced opinions in which positive aspects of the favela became salient while issues were still acknowledged.

The deconstruction of stigmas and building of global awareness of favelas can be seen as a fundamental first step in changing the landscape of neglect and police repression that has characterized policies towards these communities. “This kind of coverage is used to affirm certain policies of the state towards us,” community journalist Thais Cavalcanti told radio show On The Media last year. Perhaps we should all be reading beyond sensationalist coverage and films, and take a look for ourselves.

This is the fourth article in a four-part series on the social construction of favelas and the potential of favela tourism to break down negative stereotypes.

Phie van Rompu, M.A., graduated in Global Criminology at Utrecht University in the Netherlands. She researches state-organized crime, (de)criminalization, resistance and drug-related issues. This RioOnWatch series is based on her Masters research.

*Some names have been changed.

Full Series: Social Constructions of the Favela through Films and Tourism

Part 1: Stereotypes in Popular Films

Part 2: Glorification of War and Violence

Part 3: Favela Tourism as Resistance

Part 4: Tourist Perceptions Before and After Favela Tours