One year after the Olympic Games, and Rio de Janeiro is reeling from a wave of violence that would be unimaginable to the thousands of tourists who descended on the city last August. As of July 2, at least 632 people have been hit by stray bullets in Rio de Janeiro state, 480 have been killed by the Military Police, and 90 officers themselves have died in war-like shootouts. In response, the federal government has just deployed 8500 troops to Rio. Stories of the devastation, by and large in low-income, underserved areas and favelas, are sadly easy to come by. The son of Claudineia dos Santos Melo was shot while still in the womb, he will be born disabled. Vanessa dos Santos, a 10-year-old, was killed by a stray bullet while in her own house. Maria Eduarda Alves da Conceição, 13 year-old student and athlete, was hit and killed inside her school in Acari, followed by Hosana de Oliveira Sessassim, same age and same neighborhood, just five days later.

The city and state governments are in shock, scrambling to adjust the budget after deep losses related to Olympic Games spending, all of which is intensified by a national economic crisis and the ongoing political corruption scandal. The connection between the post-Olympic slump which has been seen again and again in cities across the globe and Rio’s slump is obvious. However, there is much more to it. Blaming Rio’s problems of violence on the Olympics or even the economic recession is to ignore the city’s history. Extreme violence has plagued the city for decades. While the Games’ inequality-boosting investments and resulting frustrations over lack of public resources, and today’s economic situation both play large roles in exacerbating the issues facing Rio residents, they have for the most part laid bare already existing problems. What are the historical trends and deliberate policy decisions that have led to the violence Rio is experiencing today? To truly understand Rio’s current upsurge in violence, we must look at the underlying causes within the context of the post-Games environment: there are eight!

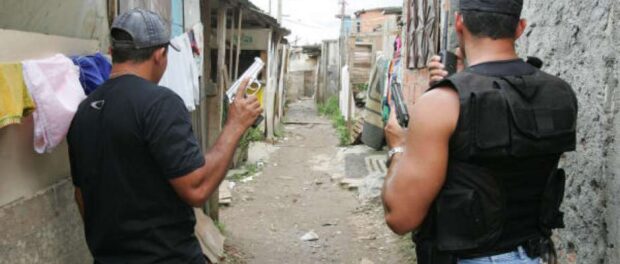

8. Failed Policing Policies

The history of Rio de Janeiro’s police force is one of violence and repression. The police force was originally created to protect the royal class against a growing slave population, and many of these historical biases are still evident. Rio de Janeiro’s Military Police, controlled by the state government, has earned the title of ‘most violent in the world’ with police killings hovering around 1,200 people each year up until as late as 2015. One damning statistic: for every 23 arrests made, Rio’s police kills 1 person, as compared to 1 for every 37,000 in the United States. However, the State decided to reform one segment of its police force before the World Cup and Olympic Games with its UPP program, at first drastically reducing these statistics to local and international praise. Regardless of any initial success, however, the program began to show problems. Why were certain communities chosen for UPP stations and others not? Where were the drug traffickers going once driven out? Where were the “community policing” strategies being lauded by the international community and advertised by the government? Eventually, with the international eye turned away, failed leadership, police corruption and less money to fund the program, and in many cases actually pay the police officers, drug gangs have made their way back into essentially all UPP favelas. In some cases, like in Maré, the program was completely abandoned and replaced with the old military-style raiding tactics. “When the Military Police come, they kill,” remarked one Maré resident. “This population has always suffered violence that is legitimized by a State that actually kills us, everyday.” With increased pressure, the government has begun to revert back to the old failed police policies, knowing fully well that they do not work.

7. Lack of Nuanced, Analytical and Balanced Media Coverage

Save from a few independent journalism organizations, Rio de Janeiro’s media often ignores issues facing favela residents. While Globo, one of the world’s largest media conglomerates and a monopolistic force in Brazilian media, recently published a spread detailing the profiles of stray bullet victims, they also recently released a video entitled “Shootout Scares Copacabana Residents.” Instead of focusing on the violence and issues facing the people living in Pavão-Pavãozinho, where the shootout took place, the outlet decided to focus on the wealthier residents beneath the favela. This behavior isn’t strictly seen in national media. During the World Cup and Olympic Games, while many international media outlets did in fact focus on favelas, few were able to authentically grasp and portray the nuanced lives of favela residents and the issues they face. Irresponsible and sensationalistic reporting, whether local or international, often suggests increased levels of violence should be addressed through increased levels of security, or solidifies ignorant and racist views of favela residents themselves. While many Rio residents support the Military Police presence, Amnesty International Brazil’s executive director had this to say, “The census conducted in Rio shows that 92% of people think that the police does not have the right to kill anyone. We need to contest the perspective and relationship between public security and the war on drugs. Everybody knows that a war produces victims and kills many people… Brazil needs to acknowledge the international protocol to protect the lives of human beings. If numbers point out that the police kills, these forces have to draw back their weapons.” To hit this point home, South Zone residents and passersby were recently asked to identify the location of war-like sounds recorded and played back to them by a campaign led by community newspaper Voz das Comunidades. Most of the participants guessed places like Syria, Afghanistan, or Africa, while what they were hearing was coming from Complexo do Alemão, a favela in their own city.

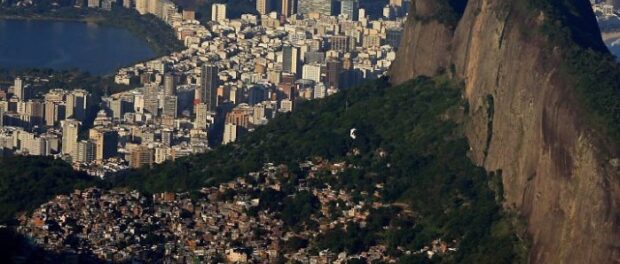

6. Entrenched Inequality

From being the port of entry of the largest number of slaves in world history, to its role as home to the nation’s first favela of Providência, Rio is a case study in historic inequality. In Rio, it’s not just the statistics that drive home the issue, it is actually the physical landscape of the city. Looking at racial maps of Rio de Janeiro, it becomes even clearer that large populations of poor, brown and black residents are subject to conditions in which their wealthier and whiter neighbors are not. One Rocinha resident notes: “This difference comes from the time slavery was abolished. Black people lived in the hills, so, black and poor people were not valued and didn’t receive support from the government. The government didn’t go there.” Simply put, many residents of Rio, including people in highly powerful positions, live with favela residents out of sight and out of mind. One wealthy resident of Barra recalled that he “always hear(s) two stories: either ‘traffickers and violence,’ or ‘good people always trying to find a smile.’” While violence is shown on the nightly news, the sad truth is that inequality and privilege–enshrined even in the nation’s highly regressive tax code–keeps the system of neglect and repression from ending.

5. Lack of Broad, Regional Thinking and Integration

While much attention has been focused on Rio de Janeiro and its South Zone, many forget the millions of citizens living in peripheral areas of the city and the broader metropolitan region. Some of the lowest income neighborhoods lie to the north and west of Rio, and regional integration has been largely neglected, a problem exacerbated by heavy Olympics investments in central areas. As drug traffickers were initially pushed out of centrally located favelas through the UPP program, they teemed to more distant communities, which have since been overrun by violence they did not experience previously. The Baixada Fluminense, to the north and northeast, has received some of this influx, on top of already experiencing greater historic violence than Rio proper. Many communities in the Baixada are controlled by local militias made of former or off-duty police officers and firemen. Marketed as providing protection from drug gangs, militias serve up their own lethal dose of violence many times praised by local politicians. To make matters worse, the Olympics served as a means to evict some 80,000 residents, most of whom were relocated to the West Zone of Rio which is chronically underserved, distant from opportunities, and also heavily run by militias, which do not allow residents to speak publicly about their problems. “In 2013, they knocked down my house. They gave some compensation, but the house was worth more,” a former resident of Praça Seca lamented, “I ran a social project from the terrace of my house. The BRT (rapid transit bus line built for the Olympics) put an end to everything.” Advertised as an attempt to “connect” the citizens of the greater metro area, much of the Olympics transportation “legacy” actually encouraged less connectivity and more violence.

4. Policies as a Marketing (Not Development) Instrument

Since times of slavery, the term “for the English to see” has been a way of describing people in power announcing (not necessarily even implementing) superficial or short-lived strategies to create an appearance of addressing long-term problems. The Olympic and World Cup legacy were full of such projects. When asked about the UPP Social program, a companion to the UPP policing policy that was meant to bring in all the other missing services–beyond security–to favela communities, one Cerro-Corá resident responded, “I don’t think they’re interested in the opinion of favela residents. They ask because they have to, so they can say they asked.” The program never resulted in the non-security infrastructure it was meant to provide. “For the English to see” tactics continue today. Recently, Rio’s new mayor released his plan for the city. In addressing the city’s growing violence, his security goals were focused on reducing non-lethal violence at the beach front. While perhaps benefiting tourists and a small portion of Rio’s elites, this short-term goal does nothing to address the root causes of Rio’s violence. It does however create an illusion for those visiting Rio de Janeiro, and lays an easy pathway to political gain.

3. Insufficient, Low Quality Social Services

Health, education, and sanitation are consistently the top infrastructure priorities among favela residents citywide, and the sorts of investments more likely to yield decreases in violence. However, these services are chronically undersupplied, of low quality, poorly maintained and underfunded, a problem made even more dire by the implementation of national austerity measures by the current presidential administration. “How can you not have a technical school or university in a favela yet you can afford to fund a massive police operation?” a resident of Acari questioned. Health and education statistics are also vastly unequal when considering region of the city. Illiteracy rates in some neighborhoods are double those of the wealthier South Zone. As a result, youth experience a ‘school-to-prison’ pipeline similar to that of the United States. All of this is exacerbated by daily violence which has closed down schools and local health facilities to avoid incident. “We are going through various difficult situations,” recalled one Maré health worker, “we even had to close the health clinic because of violence. The clinic closes, the schools close, everything closes.” This was the case when thousands of students in Alemao had their first days of school canceled for a police operation, many were notified mere minutes before the shooting began. Sadly this does not always happen, such as in the case of Maria Eduarda, who died from a stray bullet while sitting in her classroom.

2. Criminalization of Poverty

Brazil has a deep-seated history of criminalizing poverty. The poorest in Rio, particularly if they are black, are immediately at a disadvantage legally and economically because of institutionalized racism and prejudiced ideas in general, that have never been systematically addressed by the broader society. Employers frequently discriminate based on skin tone and address, making it hard for many favela residents to find formal jobs. This is made worse by the country’s current financial crisis. Brazil’s unemployment rate rose from 6.2% in December 2013 to 13.7% as of May 2017, more than doubling in just three years. Young, black men are most harmed by this statistic. Urban conflict specialist Betinho Casas Novas of Complexo do Alemão had this to say: “I represent the part of the statistics that didn’t enter into trafficking but there are people I grew up with who did. Classes, resources, and social services that provide opportunities for young people are lacking. I think that a prejudice exists that favela youth only have options to be vendors or house workers when they should be able to be athletes, journalists, teachers.” In the war on drugs, favela residents are targeted disproportionately whether they are involved in trafficking or not. In fact, only 1% of favela residents are directly involved in drug trafficking yet entire communities are treated as criminal, while the producers, consumers, and financial backers have free reign. Perhaps not surprisingly, young, black men are in turn the most likely to be killed by police and serve jail time. In the end this not only serves to further stereotypes but encourages an all out war in communities across Rio.

1. Lack of Hope

Finally there is hopelessness. What would lead you to commit a crime? Why this simple question isn’t asked more as we look for solutions is a consequence of seeing “the other” as something less than human. The World Cup and Olympics did have a positive feeling about them; Rio residents heard their representatives touting the grand projects they were undertaking and the international community was going to step in to keep watch. Between 2008 and 2010, at least five major programs were announced that could have dramatically improved the lives of low-income cariocas and favela residents across the city had they been implemented according to their guiding principles: the federal Growth Acceleration Program (PAC) and Minha Casa Minha Vida (MCMV) public housing program; the state UPP and UPP Social programs; and the municipal Morar Carioca. This last program was touted by then-mayor Paes in his TED Talk promising to bring every favela in Rio up to standard by 2020, but was ultimately abandoned. All five policies initially left favela residents palpably hopeful. As did the economic upswing and major safety net programs of those years, which had removed Brazil from the world poverty map and taken it from most unequal, to 21st most unequal, nation in a matter of 15 yeas. Up until 2013, when hundreds of thousands of protesters took the streets of Rio and millions of others did so across Brazil, there was a sense of hope that things would actually change for the better. Yet, unfortunately, the mega-events came and went and low-income, chronically underserved and marginalized citizens were left with even less opportunity than before. All five policies had been a façade. Now, in 2017, amidst the economic and political crises, and attempts to unravel the upward social mobility recently experienced by millions of Brazilians across the country, there is no longer a bright star in the distance promising a better life.

Circling back to the experience of residents of favelas with drug trafficking… As says one resident of Acari: “Everyone who lives here has seen a pool of blood or a dead body. There’s drug taking and trading in Barra and Leblon [wealthy neighborhoods]. But it is here where there are gunshots, death. Sometimes, people convince themselves the war is normal. But it is part of a system that is putting money in someone’s pocket, and it’s certainly not in ours.” It’s no wonder crime and violence are on the upsurge. And, unfortunately, there’s no chance of changing that, without undertaking the hard work of real change which means tackling the root causes of violence.