On October 3, the short educational film Is it a River or Sewage Ditch? was launched on the campus of public health institute Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (Fiocruz) in Manguinhos. The film screening was accompanied by a panel discussion and live theatrical performance by youth engaged with North Zone community-based organization Verdejar Socioambiental, who also acted as protagonists in the film. In partnership with Fiocruz, the film was developed by the Observatory of the Cunha Canal Sub-Basin, an initiative aiming to construct more participatory and environmentally-just public policies for the region, spearheaded by community-based organizations and social movements that compose the Joint Group of the Communities of the Cunha Canal Sub-Basin.

Representatives from each institution involved in the film’s production emphasized the collaborative nature of the project—uniting social movements and other civil society groups with academia and public entities in an effort to bridge grassroots forms of knowledge with technical, scientific expertise.

In a context characterized by unequal access to environmental goods, increasing pressures to subject life-sustaining natural resources to market-based logic, and the disproportionate burden of environmental problems experienced by marginalized populations, it becomes all the more urgent and necessary to effectively address the socio-environmental questions communicated through the film.

Is it a River or a Sewage Ditch?

Taking its title’s ostensibly simple question of nomenclature as a starting point, the film Is it a River or Sewage Ditch? explores the way that teenagers Andrey, Jonas, Lucas and peers perceive the Faria-Timbó River. Intended to serve as an educational tool, the film invites audiences to consider the relationship between humans and the natural environment in which we live, suggesting that the way we understand, engage with and value natural resources is critical to guaranteeing their sustenance and conservation. Through this lens, the film highlights the issue of access to and use of water resources in favelas, a highly relevant debate in light of the rampant violation of socio-environmental rights experienced by many residents of the North Zone. The North Zone is the most populous and densely inhabited region in the municipality, home to one third of the city’s population and nearly half of Rio’s favela residents.

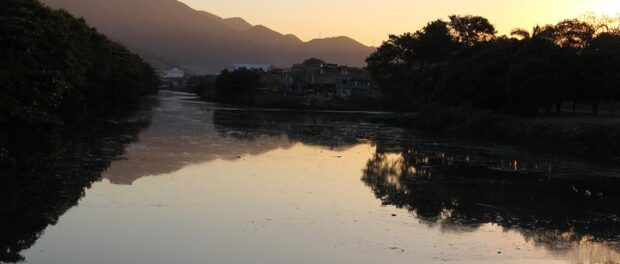

The Faria-Timbó River forms a natural boundary between the North and West Zones of Rio, flowing eastward and channeling at the Cunha Canal, which intersects the favelas of Manguinhos and Complexo da Maré before flowing into the Guanabara Bay.

Interviewed in the film, environmentalist and founder of the Baía Viva movement Sérgio Ricardo Lima explains:

The origin of this pollution has to do with a large land reclamation, constructed in this whole region here. It reduced the depth of canals and rivers that flow into the Guanabara Bay. Today we have a large problem of sedimentation. The Bay is becoming more shallow, impeding the circulation of vessels, including those of fishermen. We have here the Manguinhos petroleum refinery, which for years dumped oil and industrial pollutants into the waters of the Bay.

In the absence of universal sanitation infrastructure and adequate sewage treatment in the city as a whole, and given the heavy concentration of industry in the North Zone (where approximately 58% of the city’s industrial production takes place), untreated industrial and household effluent has rendered the Cunha Canal one of the most polluted channels to the Bay.

The negative impacts resulting from poor sanitation conditions and environmental degradation, however, are not evenly distributed. Harm resulting from degradation disproportionately impacts the health and wellbeing of residents of favelas and urban peripheries.

“Who suffers the most is the working class, the poor—principally those of African descent—and Northeasterners. So, certain groups of people are more affected than others by environmental problems,” explains Ernesto Gomes Imbroisi, the students’ teacher in the film.

Exposure to harms resulting from untreated water, sewage, and accumulated trash—coupled with the denial of access to critical natural resources upon which lives and livelihoods depend—violates these communities’ right to a healthy environment and constitutes a grave form of environmental injustice.

In this perspective, it’s essential to broaden our understanding of health. “Health isn’t only the absence of sickness,” the film’s young narrator explains. “Health has to do with people’s general conditions of life. It’s basic sanitation, education, work, housing and the environment.”

“Vamos Verdejar!”—a rallying call to protect the Serra da Misericórdia

In the film, Edson Gomes, the general coordinator of Verdejar, emphasizes the critical social and ecological role of the Serra da Misericórdia, a rocky massif and urban forest bordering 27 neighborhoods and comprising the last expansive area of Atlantic Forest in the city’s North Zone.

Although the Serra da Misericórdia gained protected status as an Area of Environmental Protection and Urban Recuperation (APARU) in 2000 and is located in Rio’s most populous zone, mining companies continue to operate quarries for concrete production in the region. Quarrying poses dangers to ecological systems including the destruction of natural springs—traditionally used by residents as fresh water sources—and land disturbance, impacting the sedimentation of the Guanabara Bay. Another alarming form of environmental degradation in the North Zone wrought by human and industrial activity is the destruction of riparian forests—trees and vegetation that border bodies of water such as rivers and reservoirs. As Gomes explains, the destruction of these protective buffers leaves the water directly exposed to negative environmental impacts, such as the erosion of riverbanks.

Gomes instructs the students in the film: “To tell if it’s a river or a sewage ditch, see if it originates from a spring or a drainage pipe. Unfortunately, most of the rivers here in this region have both… So originally it’s a river, and it turns—or appears to be—a sewage ditch, due to the way it’s treated by the population and public authorities.”

Accompanying the film screening, young cultural producers from Verdejar’s Luiz Poeta Cultural Center enacted a theatrical performance entitled “Vamos Verdejar!” As Verdejar celebrates its 20th anniversary this year, the performance recounted the organization’s history, stemming from founder Luiz Poeta’s vision and commitment to unrelentingly protect the Serra da Misericórdia from private interests and environmental degradation.

The performance concluded with a revelation of posters, reading: “The Serra da Misericórdia is one of the last green areas of the Atlantic Forest in the North Zone. The North Zone has the least green space per capita in the municipality. We have the most polluted air in the city. Enough! No to the violation of human environmental rights! Vamos Verdejar!”

In reflecting on their experiences, the youth expressed the profound impact of their involvement in the theatrical production and film upon their own relationships to the region’s waters. In the words of young actor Jonas Santos de Oliveira Costa: “Is it possible that we are responsible for this river being dirty? It’s very sad to see kids playing in a dirty river because we are the ones who polluted it. We want a better river, but in order to improve the river, we have to improve ourselves.” In this way, a degree of responsibility falls upon individuals and communities to act as stewards of the environment. In their 20 years of experience disseminating practices including agroecology, permaculture, and agroforestry, the community-based organization Verdejar has shown that it’s not only possible, but imperative, to assume this responsibility by devising alternative environmental management solutions in the face of public neglect.

At the same time, through community mobilization processes and popular participation in policy debates, authorities must be held responsible for guaranteeing basic socio-environmental rights. Fellow young actor Lucas Fernando dos Santos commented: “If we don’t show society that we have rights, we’ll continue to see this happening. It’s very important to have a conception of what will happen if we continue in this cycle.”