This is the fourth article in a four-part series on Internet access in favelas and urban peripheries in Brazil. Don’t miss parts one, two, and three. For the entire original article in Portuguese by Escola de Jornalismo Énois and data_labe published by Nexo Jornal click here.

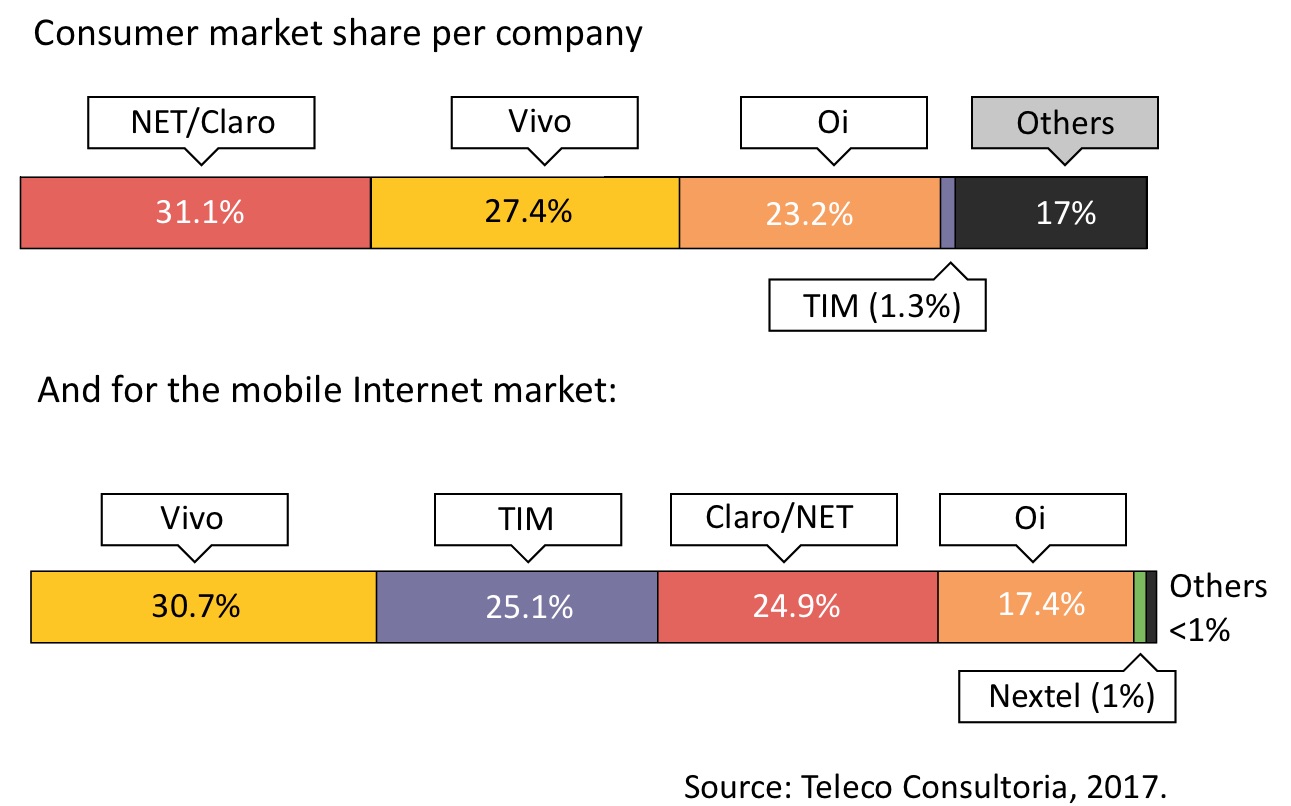

For every ten Brazilians connected to the Internet, almost nine are clients of the four biggest Internet companies. According to statistics from Teleco, a telecommunications consultancy, 83% of Internet provision in Brazil is in the hands of Claro/NET, Telefônica, Vivo, and TIM.

The scenario is similar to those of neighboring countries. In other Latin American nations, infrastructure and connectivity are also concentrated in the hands of a few companies. It’s not a monopoly situation, as there are several companies involved, but it is a situation that lawyer and Internet Management Committee council member Flávia Lefévre describes as “cartelized.” The companies organize themselves and together decide where and how they are going to offer their services, like a cartel. In practice, the connection of a good part of the Brazilian population is dependent on the four companies that dominate the market.

The broadband Internet market in Brazil is disputed between four large companies that hold the following shares of the consumer market, according to 2017 statistics from the consultancy Teleco:

“These companies, who own [Internet] provision, talk with each other all the time. They know how each other operate and where they are providing service. As such, there is no competition in the market and therefore the companies don’t worry about improving the quality or lowering the price, as they are comfortable with this set-up,” says Rafael Zanatta, a lawyer and researcher with the Brazilian Consumer Defense Institute (Instituto Brasileiro de Defesa do Consumidor—Idec).

The Brazilian Constitution says it is the duty of the federal government to guarantee the provision of telecommunications across the country. The rules are set by the National Telecommunications Agency (Anatel), which determines the parameters that must be met by Internet operators. One of these requirements is the installation of infrastructure where needed, guaranteeing Internet access to the poorest and most disconnected populations. However, in practice, this has not happened. Investment is usually conditional on the economic interest of the companies.

“Proof of this is the unequal distribution that we have today, in Brazil, of infrastructure for accessing broadband Internet through a fixed network. Even here in the Southeast, in São Paulo, for example, the infrastructure is concentrated in neighborhoods with high income populations who have the ability to pay,” says Lefévre.

“When businesses think about infrastructure investment, the logic is: I’m going install the cables and I want to have a return from this. I’m not going to put down the cables just for the sake of it.” – Winston Oyadomari, coordinator of the Household ICTs research conducted by the Regional Center of Studies for the Development of the Information Society

Questioned about the demarcation of boundaries for business operations, Anatel stated that there are no obligations for universalization on the part of Internet providers. The agency only establishes commitments to coverage in its requests for bids, determining the area in which service will be made available by the provider that wins the tender.

We contacted the main Internet providers individually to understand the criteria for network expansion and infrastructure installation. They responded collectively through their union, Sinditelebrasil: “The products that are to be made available to the population have to be linked to the existence of a real demand capable of making use of the available infrastructure.” It was not clear, however, what criteria define the “real demand.” In the peripheries, the demand exists.

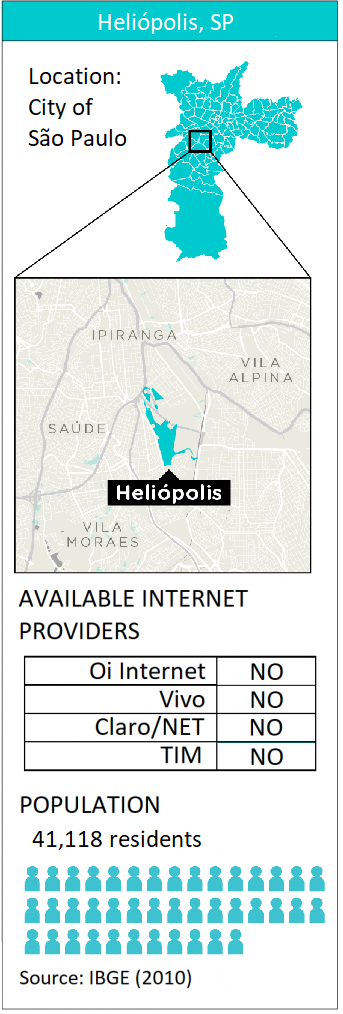

Heliópolis, one of the biggest favelas of São Paulo, is an example. Its neighbor is São Caetano do Sul, a city in São Paulo’s metropolitan region with the highest Human Development Index (HDI) figures in Brazil and where, in 2012, more than 70% of residences were equipped with broadband Internet, according to research by the Getúlio Vargas Foundation. Still, the favela is not covered by any of the four biggest Internet providers in the region. But Heliópolis does have GodNet.

This small provider emerged almost by accident. Augusto Santana, a former resident of the region, was a furniture mover and was doing a move in the Justice Tribunal building. Amongst the furniture, there were an enormous number of Internet cables that the building’s new owners did not plan to use. Santana was given the cabling, bought a Vivo link, and in 2009 began to provide Internet in Heliópolis.

This small provider emerged almost by accident. Augusto Santana, a former resident of the region, was a furniture mover and was doing a move in the Justice Tribunal building. Amongst the furniture, there were an enormous number of Internet cables that the building’s new owners did not plan to use. Santana was given the cabling, bought a Vivo link, and in 2009 began to provide Internet in Heliópolis.

In 2013, when fibre optic cables began to be installed in São Paulo, Santana retired his outsourced distribution and invested in his own equipment. With a loan from the Caixa Econômica Federal bank, Santana bought new cables, went to Paraguay for a course about the technology, and completed his first installation of high-speed Internet. The network runs from Brooklin, the well-to-do neighborhood in São Paulo’s South Zone where Santana has a data center (a data processing center, with computers and routers), to the neighborhood of Heliópolis, where it serves 1,700 families. There are 16km of cables connecting the regions.

With connection speeds ranging from 5 to 80 Mb/s and prices that range from R$79 to R$179 (around US$25-55), GodNet does not have the big providers as competitors. “They don’t consider me to be competition, really. Which is funny because I work where they don’t serve and am offering a better quality service,” he muses.

The businessman does not intend to introduce data use limits, which the big operators have discussed. The companies considered introducing the system of limited data consumption that exists for mobile networks to fixed broadband plans as well, but strong pressure from civil society led them to set the project aside.

The proposal was vetoed by the Senate, but Santana roots for its implementation. “I’m asking God that [Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation Gilberto] Kassab implements this data use limit,” he says, thinking about business. “The big businesses will adhere to it and I am not planning to do that. It’s going to be an additional advantage over my competitors. This is going to be my main weapon to get to the level of the big guys, in their areas.”

This is the fourth article in a four-part series on Internet access in favelas and urban peripheries in Brazil. Don’t miss parts one, two, and three. For the entire original article in Portuguese by Escola de Jornalismo Énois and data_labe published by Nexo Jornal click here.