Cosme Felippsen, co-guide for the Rolé dos Favelados (Stroll of the Favelados) last weekend in Rocinha, starts his tour by telling the group: “I don’t like the word tourism. For me it is a question of bringing people to the favelas because I’m from a favela and the favelas need to be heard.” Felippsen’s comments set the scene for a very different kind of favela tour: far from the controversial, externally run ‘jeep tours,’ his tour model is one that values the voices of residents, states its purpose as activism, and puts the focus on meaningful dialogue and sharing the strengths and struggles of favelas around Rio de Janeiro.

Felippsen, Providência resident and founder of Rolé dos Favelados, has partnered today with Rocinha local guide and activist Erik Martins. Martins explains how he got to know Felippsen through a newly formed Association of Favela Tour Guides, which was founded in the wake of the death of a Spanish woman who was killed by police in Rocinha while on a (not locally run) favela tour. Martins immediately identified with the mission of Rolé dos Favelados, which matched his own belief in the importance of having favela residents themselves talk about favelas, and the use of the word “activism” over “tourism.” Martins notes that external agencies are “selling poverty” and aren’t invested in positive change coming to favelas. Yet he has no issue with people from outside working in tourism in favelas: “The problem isn’t people coming from outside to work here… It’s when they come without any connections, without working with local people. They need to be honest. They need to be fair.”

“The city does not exist without the favela”

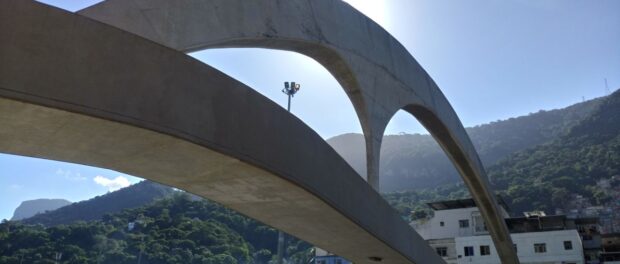

Today’s stroll starts on top of Rocinha’s passarela, or pedestrian overpass that straddles the busy Lagoa-Barra highway where Rio’s mayor recently announced works to paint the façades of Rocinha houses facing the road. This announcement deeply frustrated many residents who want to see that money spent on much-needed basic infrastructure inside the favela itself. This literal whitewashing and the relationship between the City and favela residents are among the topics discussed as the tour group stands on the Oscar Nieymeyer-designed overpass, looking in one direction towards what some consider to be South America’s biggest favela, and in the other towards nearby South Zone neighborhoods that boast some of the most expensive real estate in Brazil.

On this first stop, Felippsen and Martins introduce themselves and share with the group how they became involved in tourism and activism in their respective communities. Everyone in the group is then invited to answer the question: “What is a favela?” Of course, there is no single answer. As Martins notes, each favela is unique, with its own struggles and characteristics. Felippsen gives an overview of the origin of favelas and their ongoing and inseparable relationship from the broader city of Rio de Janeiro: “If the favela didn’t come down (the hillsides), if no favela resident left their house, the city would not function.”

Entering Rocinha, Martins leads the group to Largo do Boiadeiro, a bustling commercial area with deep northeastern influences close to the entrance of Rocinha. For many decades, there was a steady flow of migration to Rio from the historically poor northeast of Brazil, with many migrants building their homes in places such as Rocinha while working to build the city as we know it today. Boiadeiro means ‘cowboy’ and is a throwback to when livestock was sold in the plaza. Now the plaza is a commercial area by day and a music and bar hotspot by night. As Martins explains, Rocinha—with a population of at least 150,000—is divided up into lots of different areas, each with their own distinct personality.

From Largo do Boiadeiro, the group proceeds through an area that received some development projects as part of the federal Growth Acceleration Program (PAC) and the noise and hot sun quickly make way for a shaded quiet area full of trees and art. Featured here is artwork by local artist Wark da Rocinha, whose art, including the iconic angels, can be seen throughout Rio as well as around the world. The lush tree-lined streets, Martins explains, are the work of a few neighbors who teamed up to build a low fence to separate the trees from the road, and to keep the gardens watered and garbage-free.

“There is no such thing as armed peace”

Halfway through the “stroll,” the tour group stops in a plaza to sit around a table to hear about some of the issues facing favela residents today. Felippsen and Martins talk about police violence—”there is no such thing as armed peace”—Pacifying Police Units (UPPs), the war on drugs, the lack of basic state services beyond policing, the ongoing threat of evictions, traffickers, the growing evangelical movement, and a lack of quality education for favela residents. The sometimes diverging and sometimes similar stories and points of view of Felippsen, from Rio’s “oldest favela,” and Martins, from Rio’s “biggest favela,” make for an enlightening discussion which embodies the stated mission of these tours: favela residents must be heard for themselves.

For Ben, an Australian who joined the “stroll” after living in Rio for over three years “but never knowing a lot about one of the most populous and bustling areas of Rio,” the message from the guides strikes home: “I felt unsure visiting Rocinha, but it put my mind at ease that the guides were community residents who were interested in educating and sharing, rather than some kind of poverty tourism that plays to people’s morbid curiosity. I was surprised by the diversity of landscapes, cultures, and neighborhoods within the community and I came away with a better understanding of life in Rocinha and issues facing the people who call it home.”

“Rocinha is not a monster”

As Martins leads the group through Rocinha, the concept of favela as community is clear: people stop to greet the guide and are also happy to chat with the visitors. The group meets a local samba artist, one of the men who cares for the beautiful green space mentioned above, two stars of the soon to be released AREP (a movie filmed in Rocinha), Martins’ sister who works as a model, a number of other local tour guides (both on and off duty), business associates of Martins’ dad… the list goes on! What is unspoken is what can often be most powerful: here in Rocinha, people go out of their way to stop and make visitors feel welcome, and the sense of community among residents is everywhere you look. This coincides with another of Martins’ missions: to combat the messages from mainstream media and “show people that Rocinha is not a monster.”