This is the first part of a two-part series consisting of interviews with two speakers at the 12th Brazilian Conference on Collective Health (ABRASCÃO) in Manguinhos. Read the second part here.

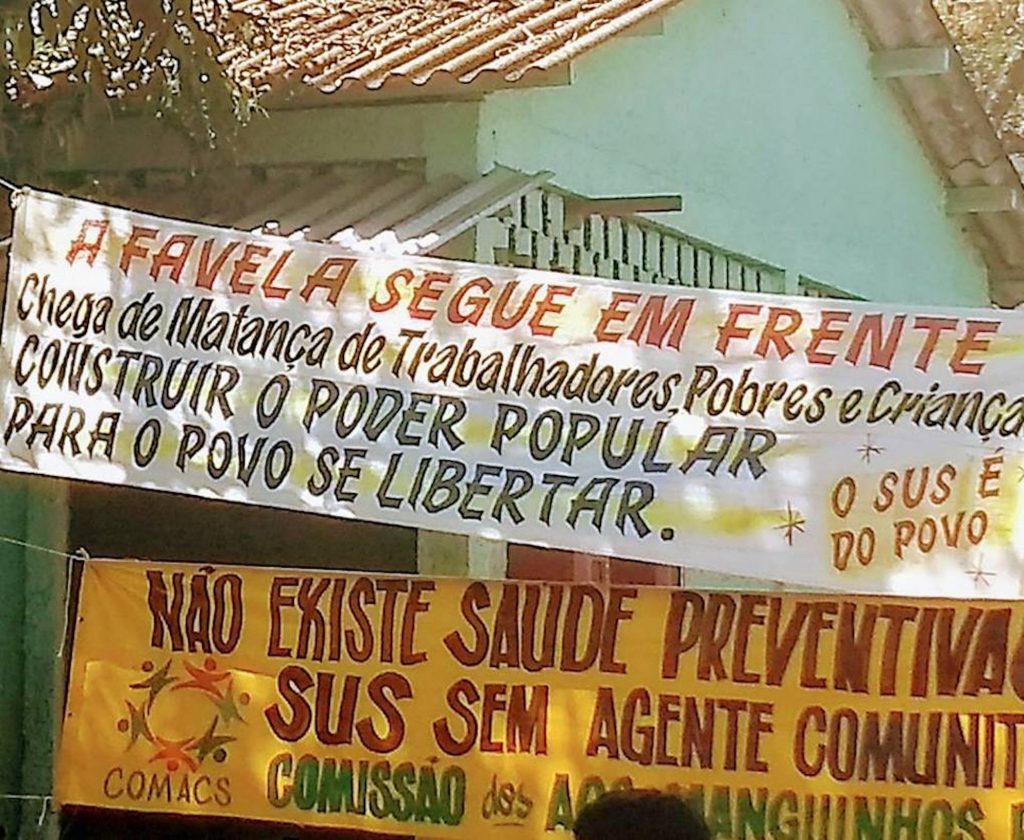

Between July 26–29, Brazil’s national health institute Fiocruz hosted the 12th Brazilian Conference on Collective Health, organized by the Brazilian Association of Collective Health (ABRASCO). This year’s event, nicknamed ABRASCÃO, was centered on the theme of strengthening Brazil’s Unified Health System (SUS), rights, and democracy. These discussions are especially important in the current scenario, which includes the dismantling of SUS, regression in labor laws, the downgrading of public education (from elementary to university levels), and the privatization of goods and national resources. The majority of these actions lack public participation, not to mention public approval.

The audience at the conference was the scientific community, but representatives of social movements were invited to share their work and prompt discussions at some of the panels and roundtable discussions—reflecting a higher degree of participation from social movements relative to previous years. However, the lack of governmental funding for the conference resulted in extremely high registration fees, impeding the participation of many people—especially residents of the local area (which includes a number of favelas, namely Manguinhos).

The community news collective Fala Manguinhos! published coverage of the event at the invitation of the Fiocruz Social Cooperative, which also supported the participation of other collectives and organizations from favelas. We saw this invitation as an opportunity to share and popularize the content of the generally cost-prohibitive event. To bring the debate closer to residents of Manguinhos—helping provoke ideas and proposals about public health stemming from the territory—we live-streamed the lectures and conversations on our Facebook page.

Also with the intention of disseminating the knowledge circulated at the event, we interviewed two speakers. The first interview is with Leonídio Madureira, coordinator of the Fiocruz Social Cooperative, who participated in the roundtable “Strategies for the Promotion of Health and Democratic Territorial Management in Favelas.” The interview with Patrícia Evangelista, activist and resident of Manguinhos, is covered in the second part of this series. See the interview with Madureira below:

Edilano Cavalcante: What is the significance of the theme of the event, and of it taking place here at Fiocruz?

Madureira: More than 8000 people participated in the lectures, seminars, roundtables, discussion groups, and cultural activities over these four days. They were four intense days, in which researchers, workers, students, health advisors, and social movement representatives presented their studies, proposals, and motions to strengthen SUS, rights, and democracy. It is important to highlight that the conference enabled exchanges, reflections on health practices, political mobilization for collective health, and the connection of different groups that are active in the struggle for the right to health.

Holding the ABRASCO National Conference at the Manguinhos Campus, in my view, means a lot for Fiocruz because the theme of “Strengthening SUS, Rights, and Democracy” is directly aligned with Fiocruz’s fight for better living conditions for the population and its commitment to democracy and citizenship in our country.

The final document of the conference—a series of directives for the whole community fighting for collective health—will also influence Fiocruz itself. These include: “defending a democratic, just society that is respectful of diversity, solidarity, and is oriented towards equality—with strategies to promote social, cultural, territorial, gender, and ethnic equity and fighting against all forms of violence, intolerance, discrimination, homophobia, segregation, and exclusion;” “defending the right to health and the Unified Health System—in its effectively public and universal character—as a pillar of the social protection system and a political project of the nation and the Brazilian people;” and “defending the maintenance and advancement of the guarantee of comprehensive care based on national oral and mental health policies, and pro-equity policies for the health of LGBT, rural, black, and indigenous populations.”

EC: Fiocruz is based in Manguinhos, one of the most impoverished neighborhoods in the city of Rio de Janeiro. Among many others, one of the most urgent rights to guarantee is the right to life. This right is routinely violated in the roads and alleys of Manguinhos, and in favelas in general. Was health discussed from the perspective of public security at the conference? Did favela residents participate in this debate?

Madureira: At the conference, there were discussions about public policies related to public security, the war on drugs, and the genocide of black youth in Brazilian favelas. These themes were debated with participation from conference attendees from other Brazilian states. It is worth noting the context of the federal military intervention in the Rio de Janeiro State Security Secretariat, which has spurred nearly a 40% increase in the number of shootouts in Rio’s favelas and in the metropolitan region. Diverse points of view were highlighted during the roundtables, discussion groups, and at the opening and closing panels with the affirmation by Fiocruz President Nísia Trindade that lives in favelas matter.

Participation was diverse. Representatives were present from the Popular Movement of Favelas, NGOs (including Redes da Maré and the Favelas Observatory); collectives (Coletivo Papo Reto and Movimentos); and workers and health advisors from Manguinhos and Maré, as well as from favelas in other states.

EC: How can we think about the democratization of health in favelas from a prevention perspective?

Madureira: SUS is innovative compared to previous health policies in that it focuses not only on prevention or assistance but rather expands healthcare actions—incorporating the dimension of health surveillance and the promotion of health. With this, the idea of prevention that blames people for their illnesses with a focus on hospital-centric care is remedied. In the scope of SUS, under the principles of universality, integrality, and social participation, healthcare is created not only for people but with people. In this sense, it is important to strengthen and improve the mechanisms of participation that exist in the healthcare sector—but also to guarantee the presence of the State through effective, transparent, participatory, continuous, and territorialized public policies.

EC: Does this relate to the creation of healthy territories, one of the objectives of Fiocruz?

Madureira: Territory is a term with many meanings, especially given its use in different disciplines. An important part of the literature in the field of health is the discussion of territory in terms of power relations, which is important when considering how a territory can be healthy. In thinking about what is “healthy,” we come to recognize that health does not exist without adequate housing, employment, recreation, quality public transportation, and public security that preserves life and values rights, among other elements. In this sense, a healthy territory is formed as a social space in which the most diverse aspects of public policy coalesce to operate with a focus on human and environmental life—acting equitably through participatory mechanisms and adjusting to territorial dynamics where the policies are enacted. In an unequal country like Brazil, where democracy has not even been fully implemented, it is essential to create and strengthen organized and collective actions and establish mechanisms for territorial democratic governance—especially in the peripheries, impoverished neighborhoods, and favelas.

EC: How does ABRASCO plan to democratize the ideas, learnings, and goals put forth during these four days and make them widely available? And what is the next step to continue debating healthcare and the guarantee of rights?

Madureira: Since members of the Fiocruz community contributed to the debates in diverse thematic areas and fields of discussion related to collective health, they will also absorb the contributions put forth in the lectures, lectures, panels, and roundtables that took place at the conference. In general terms, we can note that these contributions will reverberate in institutional actions and will influence debates in technical chambers and at Fiocruz facilities.

The motions and the final document approved at the conference can be utilized by organized social movements, management councils, researchers, and grassroots healthcare education activists to guide debates and actions, together with the population and health workers such as Community Health Agents (ACS).

This article was written by Edilano Cavalcante and produced in partnership between RioOnWatch and Fala Manguinhos! (Speak Up Manguinhos!). Cavalcante is coordinator of the community communication agency Fala Manguinhos!. As a community communication initiative produced by and for Manguinhos, Fala Manguinhos! was set up to defend human and environmental rights, and to promote citizenship and health with the direct participation of residents in the decisions that involve the Community Communication Agency of Manguinhos, from the meetings of the communication group and the Community Council. Follow Fala Manguinhos on Facebook here.