For the original article in Portuguese published by the Institute of Alternative Policies for the Southern Cone (PACS) on Medium, click here. Reporting by Gizele Martins and Jessica Santos in partnership with the Brazilian Fund for Human Rights. This is the first article in a five-part series.

“I heard the shot from my home, but I didn’t imagine that it would be the shot that killed my son. He was 21 years old, shot in the back, and the police had the nerve to declare the case as an ‘act of resistance.’ It was the first time that I felt racism on my skin.”

The quote is from a 47-year-old woman, a resident of one of the favelas in the North Zone of Rio de Janeiro, whose son was killed one month ago by the Military Police. Statements like this are constant in the city’s favelas and peripheries. These facts are common: the circulation of war tanks; vexatious searches; the presence of armed soldiers; the extensive use of helicopters in operations in favelas; the increase in the number of forced disappearances, mass assassinations, and, consequentially, the increase of so-called “acts of resistance“—deaths resulting from police action. These are some problems faced by residents of Rio de Janeiro in light of the military intervention implemented by President Michel Temer’s administration on February 16, 2018. All of these actions are justified by the supposed crackdown on violence, making use of exceptional legal instruments such as Operations for the Guarantee of Law and Order (GLO)—operations established by the Brazilian Constitution to be carried out exclusively by order of the president, who may authorize the use of military forces.

In these first months of the intervention, data collected by relevant government agencies show that there was an increase in the number of acts of resistance cases relative to last year. Data from the Institute of Public Security (ISP) indicate an increase in homicides resulting from opposition to police intervention. In the first six months of 2018, a total of 766 cases were documented—the highest number since 2003. In the first five months of the military intervention, 4,005 shootings or gunshots in the Rio de Janeiro Metropolitan Region were registered via Fogo Cruzado (an app that monitors shootings in Rio). There were 2,924 shootings in the previous five-month period.

From January to July, there was more investment in so-called public security than there was in healthcare, education, citizenship, and other rights.

“This materializes when the State Treasurer’s Office says that the budget for Rio’s public security, presently under military intervention, has increased by 136% over the past ten years. The amount of funding jumped from R$5.2 billion (US$1.3 billion) in 2008 to R$12.2 billion (US$3 billion) in 2017,” highlights Fransérgio Goulart, a researcher from the Grita Baixada Forum, a social movement located in the Baixada Fluminense.

Temer legitimized the military intervention in Rio as a response to what is classified as cargo theft. Once again, the government seeks to deliver quick responses to businessmen without measuring the consequences for the lives of the favela population. Once again, it is favelas that suffer from the increase of military power with war tanks and the use of GLO operations, violating the very principles of democracy.

“This period of military intervention is the expansion of a policy of confrontation. Consequently, people are dying. From the moment in which you see the need to resolve the problem immediately, you ignore the right to life and all other rights of the poor population. Furthermore, there is a total lack of investigation, whether due to tampering with crime scenes or the lack of prepared technicians. Another fact is that the more police kill, the less they make arrests. This is the situation that we are currently experiencing,” states Thales Arcoverde Treiger, a federal public defender.

According to Treiger, the challenge is to go beyond the numbers compiled by government agencies and find loopholes in the increased number of act of resistance cases because the intervention has generated confusion over who should respond, who should investigate, and to whom cases should be referred.

Who Investigates the Army and the Police?

In the context of increased massacres, forced disappearances, operations, and act of resistance cases, groups that take part in favela movements—together with the Rio de Janeiro State Public Defender’s Office, the Federal Public Defender’s Office, and the Human Rights and Citizenship Commission of the Rio de Janeiro State Legislative Assembly (ALERJ)—organized an agenda of visits to over forty favelas and peripheries across Rio called the “Favelas for Rights Circuit: No Intervention!” The objective is to gather statements, hear residents, and learn about the violations suffered in favelas and peripheries and about the violations that residents have now begun to experience, stemming from the understanding that these are the people who most suffer and will continue to suffer from militarization.

More than ten visits have already taken place since March. Resident testimonies recount a rise in home invasions, theft of money and objects, missing persons, mass assassinations, and vexatious inspections—especially of young black people—in addition to the increase in the number of cases that appear to be “acts of resistance.” In just one favela in the West Zone of Rio, over the course of one week of operations—with the use of armored vehicles, helicopters, Civil and Military Police forces, and war tanks—22 people were killed and only six bodies appeared, all of which were registered as acts of resistance. The others are disappearances, just like in the 1990s. The situation is the same in other favelas and peripheries.

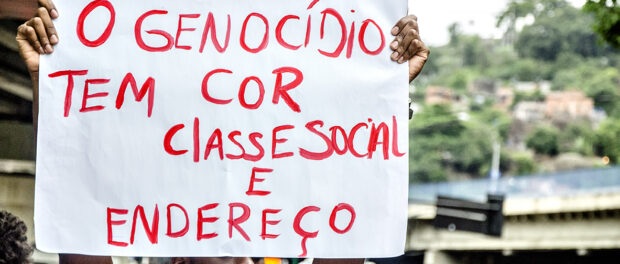

In this context, the relaunch of the “No Tanks!” Campaign also works to give visibility and to pressure the judiciary to investigate these cases. According to data from members of the campaign, the number of homicides resulting from police intervention in the state of Rio increased 96.7% in March 2017, relative to the same period in 2016—going from 61 to 120 victims. According to data from the IPS, 813 people have already been killed by police in the state of Rio de Janeiro between January and September of this year in homicides in which the police allege to have acted in supposed legitimate defense. Another piece of data that draws attention is the fact that 46% of the homicides in the entire state of Rio de Janeiro are concentrated in the Baixada Fluminense [the municipalities just north of Rio de Janeiro but within its metropolitan region]. The campaign also has been fighting against racism in the legal system.

“More than 90% of ‘acts of resistance,’ when we manage to bring them to trial, are archived by the court—even with forensic evidence of shots to the victim’s back. The victim is then typically accused based on a racist question that many judges ask of the mothers and relatives of victims of state violence: whether the son had any involvement with drug trafficking. With this question, they make the victim seem like the perpetrator. The trial was supposed to be about the violation committed by police, and not about whether or not the victim was involved in drug trafficking, especially since all of us who live in favelas coexist with the presence of drug traffickers,” explains Goulart.

According to Goulart, an activist and researcher, the campaign organized demonstrations in front of the Public Prosecutor’s Office to denounce this and other racist actions by the judiciary. With these demonstrations and the leadership of mothers and relatives of victims of state violence, there was an aperture within the Public Prosecutor’s Office—by means of the Special Action Group for Criminal Enforcement and the Human Rights Advisory—which resulted in reopening some cases that had been stalled.

“We need to understand that there is a racist public security system, where, as victims’ mothers and relatives say, it is the police who pull the trigger and the racist judiciary that absolves the murderer,” Goulart explains.

‘Acts of Resistance Followed by Death’ Cases Increase, Investigations Decrease

Historically, the favelas and peripheries of Rio de Janeiro face violations committed by government agencies, particularly with regard to public security. In these impoverished spaces, home to a majority black population, the order to kill is legitimized by authorities on the premise of a false “War on Drugs” discourse.

Proof of how the criminalization of poverty and racism works in favela spaces can be found in the 1990s when the police began to receive so-called “Wild West payments.” It was then that the legal mechanism known as the “act of resistance” gained prominence. Present since the time of the Military Dictatorship, this administrative classification has been increasingly used to designate deaths resulting from police action. During the gubernatorial administration of Marcello Alencar, the use of the instrument was stimulated by payment granted to Military Police officers, deemed a “reward for bravery” or “Wild West payment” (for acts typically resulting in the deaths of suspected criminals).

The act of resistance classification was created in 1969—following the AI-5 (Institutional Act Number Five of December 1968)—as an internal measure within the police force to justify and minimize the red-handed arrest of police officers who had committed homicide. Immediately, it began to be used by the press, naturalizing officers’ versions of incidents with forged crime scenes (teatrinhos, or “little theatrical scenes,” as they were known at the time) in order to justify the murders of tortured political prisoners—which were also sometimes explained as resulting from “excess treatment” or “suicide,” according to João Costa of the Torture Never Again group.

For Patrícia Oliveira, a member of the Rio de Janeiro State Mechanism to Combat Torture, this instrument led to the creation of “extermination groups” (death squads) and to the dramatic rise in massacres.

“At the time, the most deadly police were those who earned the most. They received a bonus known as a ‘Wild West payment,’ which greatly increased the number of people killed. Several cases of murdered children and teenagers emerged. There were constant operations in favelas. Several extermination groups emerged—for example, the Running Horses. From there, several massacres in Rio de Janeiro came to light. The police showed its true face at that moment,” she says.

The Running Horses, cited by Oliveira, was an extermination group formed by police officers from the 9th Battalion of the Rio de Janeiro Military Police. They were responsible for the 1993 Vigário Geral massacre, which resulted in 21 victims.

In the face of the increase in massacres and act of resistance killings in the 1990s, social movements from favelas—together with human rights organization Amnesty International—began to pressure the government at the time to commit to investigating these cases.

In 2007—more than a decade later—once again, the numbers of massacres and acts of resistance increased in favelas and peripheries. According to Oliveira, this increase in 2007 had to do with policies, practices, and the biases of authorities and society as a whole towards the resident population in these territories. “The number of cases increases when we have governors saying that the solution will only arise from investment in public security. An example is when Sérgio Cabral, former governor of Rio de Janeiro, said that ‘women from favelas are factories for producing criminals.’ This is a public official spreading hate speech and violence and saying that he will resolve the problem with more violence,” Oliveira decries.

In 2008, Pacifying Police Units (UPPs) were implemented in some favelas in Rio de Janeiro. Over the past ten years, UPPs have been installed in 38 favelas. Researchers on the topic affirm that in the initial years of UPPs, there was a decrease in act of resistance cases in these favelas but a rise in the number of disappearances, according to data from the report Acts of Resistance: An Analysis of Homicides Committed by Police in the City of Rio de Janeiro (2001–2011), coordinated by Professor Michel Misse of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). Parallel to the deployment of UPPs, since 2009, the State Secretary of Security has created a set of targets to reduce some indices of violence, including intentional homicides.

Since 2011, this program has included targets to reduce violent lethality, such to include not only intentional homicides and robberies—included in the initial decree—but also bodily injuries followed by death and acts of resistance followed by death. This status demonstrates the government’s recognition of the excessive use of this mechanism.

For the State Secretary of Security, as for some public security scholars and social organizations, the implementation of UPPs in favelas and peripheries served as a way to combat drug trafficking. Favela residents and their family members, however, affirm the contrary: that these policies represent yet another way of controlling the black and poor population. Juliana Farias—a researcher on the topic and supporter of mothers and relatives of victims of police violence—affirms that this program is, without a doubt, yet another racist practice on the part of public authorities.

“Public security policies are racist; public sector bureaucracies are also built with a racist rationale. It isn’t possible to speak of decreasing acts of resistance followed by death while still believing that there is an enemy to be fought (keeping in mind that according to this racist logic, ‘enemies’ are necessarily black male residents of favelas and peripheries),” Farias concludes.

This is the first article in a five-part series.