Originally constructed as a workers’ village for employees of the local fabric factory, Chácara do Algodão is a small community with a long history interlaced with the rise of Brazil’s textile industry located in the Horto neighborhood, in Rio’s South Zone.

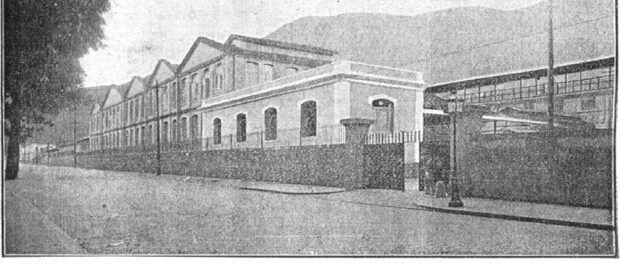

The first cotton mills were unveiled in Brazil around 1845, growing rapidly to make the textile industry one of the nation’s most important well into the 20th century. According to historian Stanley J. Stein, the cotton textile industry was largely responsible for jumpstarting Brazil’s industrialization and alleviating the country’s reliance on exporting raw goods. Fabric manufacturer Companhia América Fabril was a major player in this story. In 1915, at perhaps the height of its operations, the company employed 3,100 workers and had 2,170 looms and 85,205 spindles across four factories. It was the largest textile company in Rio de Janeiro at the time and at one point, the largest in Brazil. The factory was founded under a different name in 1878 (when Rio was the capital of the Empire of Brazil) in Magé, a municipality in Greater Rio de Janeiro, and became known as América Fabril after merging with another major factory.

Following the declaration of Brazil’s independence, the government of the early republic sought to stimulate industrialization. Benefiting from policies enacted under the guidance of finance minister Ruy Barbosa, América Fabril grew rapidly and eventually acquired a factory in Horto, Fábrica Carioca, in 1920. Situated where media conglomerate Rede Globo now stands, the factory had been granted the license to build on federal land in 1889 in hopes that the industry would stimulate the economy and attract workers to Brazil. One of those workers was the grandfather of Maria da Glória Alves, known as Glória, who continues to live in the community of Chácara do Algodão.

“I had a wholesome childhood, there was everything here. There were outdoor movies and soccer. The school was right here. We played day and night here in the street. During Carnival, there was a factory block party. At Christmas, all the kids left with a toy and with clothes. My upbringing was here together with the other families. Here everyone was an ‘aunt,’ everyone was friends. In those times, only one household had a TV and they invited us to watch—a room full of children. Everyone was family,” Glória recalled.

Glória was referring to the vila operária, the workers’ housing that attracted people from across the region and world to work in the factory. It wasn’t the only workers’ village in the area; several other institutions, including the Botanical Gardens itself, created housing for their employees. América Fabril’s workers’ village in Horto became known as Chácara do Algodão. As Glória stated, Chácara do Algodão had everything that a community might need: a school, a sports club, leisure areas, events, and parties—like the famous carnival block party. Glória’s grandfather, mother, aunt, and other family members all worked in the factory; it was truly a family ordeal.

However, a crisis hit the textile industry in the early 1960s and the factory in Horto was shut down soon thereafter, in 1962. In an attempt to save the company, the Central Bank of Brazil (BCB) transferred funds to an investment bank, which then invested in the company. Nevertheless, the attempt failed, and control of the company’s assets was handed over to the bank. While the company technically still existed, much of the land was sold to Rede Globo, while the former employees were left in their houses.

Dirty Business

For a while, life went on. Workers found new jobs; Glória’s mother followed América Fabril to its factory in Tijuca, in the North Zone. The city of Rio de Janeiro even passed Municipal Decree 7313 in 1987 authorizing the cultural preservation of the Chácara do Algodão workers’ village, citing its importance to the city’s history and to those families in need of affordable housing.

Shortly thereafter, however, América Fabril began pressuring residents to leave in spite of the municipal decree. In response, the community entered into a federal lawsuit to initiate a collective land titling process, which began in 1989. While the eviction order was halted, the company attempted to divide the community, suing each family separately in state courts in 2001 for neglecting to pay rent. Then came the smokescreen that would forever alter the composition of the community.

América Fabril hired a lawyer to convince individual family members to sell their houses or “officially” buy them, giving up their stake in the federal collective land titling case. The houses were later resold at a much higher cost, plausibly in an effort to pay off América Fabril’s debts to the Central Bank. “The factory created a smokescreen to prevent us from seeing that it was a collective case, then individualized and criminalized the [land titling] case to be able to do this type of thing. This land was given to América Fabril with the purpose of doing social good, to build a factory and bring skilled workers here… They gave the workers homes so they could live nearby. However, when the government ceded the land, it was meant for social good—not for real estate speculation. The factory then took it and speculated on federal land. They divided it up and sold what wasn’t theirs. This land was granted with the purpose of generating income tax for the government, jobs—these types of things—for a social purpose,” stated Jorge Alves, a longtime resident.

Prior to the court case brought by América Fabril, residents were only charged a small fee for upkeep of the community and stopped paying once the factory shut down. According to residents, the company used these receipts claiming they were rent payments and that residents had stopped paying. Then, the company hired a private lawyer to intimidate residents into selling or buying their houses to avoid further lawsuits, thus giving up their stake in the federal collective land titling case.

The sale of the land where the community is located—originally ceded to the factory for the purpose of developing workers’ housing—to the highest bidders in order to pay off the debts of a bankrupted private company stands in direct opposition to Clauses 22 and 23 of Article 5 of the Brazilian Constitution, which states that land must serve a social function. Community members remember the remaining cases being decided very quickly with most residents losing, including the Alves family. It wasn’t until public defenders from the Land and Housing Nucleus (NUTH) delivered a petition to halt the cases until the federal collective land titling case was decided that things calmed down.

Much damage had already been done, however. The community of 200 families had been reduced to 23. Some families “bought” the right to their houses and land, but simultaneously gave up their spot in the federal land titling case. Others sold out for fractions of their worth. While the community is still intact, it is now a small patchwork of the original families who continue to resist. Community leader João Paulo Barbosa Alves stated: “We’re experiencing the legacy of [early 20th century instigator of urban renewal] Pereira Passos, which hasn’t ended, it continues: this legacy of eviction. This legacy where the poor, mixed, black, indigenous, or Italian immigrant working-class people don’t have the right to live in Horto. Here, what’s happening is the continuation of the cycle of evictions that has always existed in Rio de Janeiro. Geographically speaking, we live in a privileged place but financially speaking, our family does not have this privilege.”

Gentrification

Another major theme becomes apparent when studying the case of the community of Chácara do Algodão: gentrification. Why push forward when there are so many holes in the federal government’s case for eviction? Luiz Claudio Barbosa Alves, a community leader, replied: “As I understand, it’s related to the exclusion of the poor from the South Zone. There was even a judge, who, when the public defender went to submit the petition for injunction, said, ‘I’m a judge and I can’t live there. Why should they get to live there?’ To me, it’s very explicit how much this land is worth and how we haven’t historically been able to overcome this class dispute, with racial dimensions as well.”

Indeed, gentrification in the area is apparent from the moment one arrives. As Luiz Claudio Alves and his brother João Paulo explain, the whole area used to be known as Horto when they were younger. The map below sourced from Jornal Vozes do Horto shows the historical extent of the neighborhood; number fourteen shows Chácara do Algodão. Slowly but surely, the upscale neighborhood of Jardim Botânico is growing, chipping away at Horto, which was once considered to encompass the entire area. Houses of celebrities can be spotted in the hills lurking over the community. While the resisting 23 families are legally barred from making changes to their houses due to the cultural heritage decree, the rest of the community looks freshly painted and hosts fancy new shops and boutiques. The Alves brothers now say they live in both Horto and Jardim Botânico, depending on who asks. While the area’s gentrification is highly visible, the process it entails is not simply limited to aesthetics.

“One single bread roll costs R$1 (US$0.25), so the gentrification starts there. You are inside the bubble of the South Zone, where life is getting more and more expensive. You don’t have the social conditions to break out of this and life continues to become more expensive. This is gentrification. You don’t feel it. Speculation is driving up consumption, driving up the cost of living—but salaries aren’t going up with it. To give you an idea, I’m the first in my family with a college education and my brother was the first to attend a public university. You walk through life within a power structure that doesn’t give you the necessary access to get a job that would allow you to make enough to pay for a R$1 bread roll,” stated Luiz Claudio.

Moving Forward by Looking Back

The Alves family is not giving up without a fight. Jorge quipped: “They are going to bother us until the end but nothing stops us from fighting for our rights until the end as well because they are constitutional rights.” The Alves family believes that the community of Chácara do Algodão is special and that its story deserves to be remembered, told, and preserved. In fact, in the original decree declaring Chácara do Algodão an area of historic preservation, it was noted that the community serves as a valuable record of the history of the city of Rio de Janeiro.

Now in their fifth generation, the Alves family is pushing to organize the community and educate people on the history of workers’ villages. Chácara do Algodão bears the marks of the hard work put in to construct the nation, a community built around family. As Glória recalled: “I have always lived here, 61 years living here. This is the place where I was born, where I got married, where my daughters, grandchildren, and great-granddaughter are.”

Glória’s grandfather died in an accident while on the job. He gave his life serving his country, company, and family. His memory—and that of countless others—lives on in the streets and homes of Chácara do Algodão. For now, residents await the decision in the federal collective land titling case, which, depending on the outcome, could potentially set a significant precedent as a housing rights victory or uproot 23 hard-working multi-generational families. Meanwhile, residents are organizing, hoping to show the true importance of preserving the community. As João Paulo reflected: “There have been a lot of people that have passed through this house—many family members who have fought for me to be here today. I think the most important struggle for me at this moment is to be able to unite and try to understand what exactly workers’ villages are and what is at stake here. For me, there is the question of housing but there is also the cultural importance of this street and others. It’s a fight for housing, but it’s also a fight to preserve our roots. Today, I fight for my family’s roots. I cannot talk about my life without acknowledging this house.”