Here on RioOnWatch we regularly report on land rights struggles in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas. With this focus in mind, on occasion we may publish articles such as this one, highlighting broader land rights conflicts across Brazil, and even the world.

In the early morning hours of Saturday, April 6, residents of Acará, a municipality outside of Belém, capital of Brazil’s Northern state of Pará in the Amazon region, awoke to the distressing news that a transport ferry had crashed into the support pillars of a major bridge in the area, causing it to fall into the Moju River. The bridge formed part of the Alça Viária transport corridor, linking Belém to the interior of the state.

It is still unknown whether anyone was killed or injured in the accident, but in an interview with O Globo, local resident Adriana Lameira reported hearing loud noises and “people crying for help” as the bridge fell. Lameira and her husband Vagner Carvalho even claimed to have seen a car fall into the water as the accident took place. Firefighters rescued crew members from the boat that caused the accident and continued their search for additional victims on Sunday and Monday. In the meantime, residents of the area are in an official state of emergency and will be unable to access main roads, hospitals, schools, and community centers for an indefinite period of time.

Ignoring the role of anti-environmental public policies in causing fatal disasters that impact local residents, at a press conference on Sunday morning, Helder Barbalho, governor of Pará, insinuated that the structure of the bridge was singularly to blame for the incident and publicly committed to ensuring “speed and security in the maintenance [of the bridge] to guarantee the region’s indispensable mobility.”

The ferry that caused the accident was transporting palm oil residues (to be used as fertilizers) that were purchased directly from palm oil conglomerate BioPalma. BioPalma is a lesser-known subsidiary of Vale S.A., the international conglomerate whose negligence caused the fatal mining disasters in Brumadinho and Mariana. In Brazil alone, according to Amazon Watch, Vale is implicated in land grabbing, tax evasion, intimidation of employees, water contamination, promotion of child prostitution, and illegal labor practices.

Since BioPalma began operating in Pará in 2012, the company has been embroiled in constant conflicts with local communities, land rights activists, and former employees. In 2015, a group of indigenous activists occupied a BioPalma plantation in Comarca de Acará, Pará to denounce illegal deforestation and agrochemical pollution. On April 15, 2018, a 33-year-old quilombola leader named Nazildo dos Santos Brito, who had organized the protest in Acará, was brutally murdered. Three months prior to Brito’s death, he had unsuccessfully petitioned the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office for protection, protection he deemed necessary because he had been threatened by BioPalma employees who were angered by his resistance to the use of indigenous land for palm oil production. In January 2019, a police investigation concluded that local palm oil farmers had killed Brito, but refused to comment on BioPalma’s connection to the case. Unsurprisingly, Vale S.A. and BioPalma also kept silent. In an interview with Amazonia Real, Brito’s widow Ivonete dos Santos said her husband wanted to “build a better future for the kids that are being born into [their] community” and repeatedly emphasized that her husband was murdered because he refused to give up his land to the palm industry. “Everyone is scared,” said Santos, but “we can’t let [Brito’s dreams] die.”

BioPalma was again implicated in human rights abuses in 2018 when a former employee sued the company for illegal labor practices. The plaintiff was forced to work “rain or shine” from 6am to 6pm with only a 15-minute break for lunch. Depositions from the case revealed that BioPalma did not provide employees with potable water or bathrooms on their palm plantations. BioPalma received a small fine from the government, but their operations in Pará were essentially uninhibited.

In a brief statement on Tuesday, April 9, BioPalma denied responsibility for the Alça Viária accident and claimed—but did not prove—that the palm oil residues were being transported by “a third party.” Pará state officials continued their pattern of impunity towards Vale S.A. and BioPalma and maintained their silence on the matter.

BioPalma states in all of its public documents that the company maintains strict human rights and environmental standards. As shocking as this may seem, BioPalma has reason to feel comfortable making these brazen claims. Vale S.A. and BioPalma are members of the United Nations Global Compact (UNGC) and the Corporate Human Rights Benchmark (CHRB). These prestigious organizations are responsible for monitoring and verifying the human rights and sustainability practices of their member companies. However, although Vale S.A.’s mining activity was admonished by the CHRB after Brumadinho, neither organization has ever specifically condemned BioPalma’s abusive behavior in Pará. In fact, UNGC and Vale S.A. have jointly published documents that praise BioPalma’s “charitable efforts” in the region. As recently as November of 2018, just months after Brito’s murder, the CHRB stated that the company had been “improving its human rights management through initiatives such as risk management and socio-environmental impact, due diligence processes, increased of complaints and greater transparency in the disclosure of company information related to the topic.”

BioPalma is not the only palm oil producer guilty of damaging local infrastructure and violating human rights in Pará. In fact, a nearly identical incident occurred in March of 2014, when a licensed AgroPalma boat crashed into another bridge over the Moju River and caused it to collapse. AgroPalma sells its product to numerous food, beverage, and home goods manufacturers. The company is recognized by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), the preeminent certifying body for palm oil companies, as a “supply chain certified” (SCC) company. RSPO is a multi-stakeholder initiative comprised of producers, consumers, and environmental NGOs (The World Wildlife Fund and The Nature Conservancy). RSPO claims to promote “the growth and use of sustainable oil palm products through credible global standards and engagement of stakeholders.” Companies like BioPalma and AgroPalma tout RSPO SCC certification, as well as other labels such as “organic” and “fair trade” as proof that their palm oil supply chain maintains strong environmental, safety, and human rights standards. At the time of the 2014 crash, a spokesperson for AgroPalma claimed that the company had no liability for damages because the boat was operated by a contractor. This contradicts RSPO guidelines, which mandate that AgroPalma and all other RSPO-certified bodies are responsible for any accidents or ethical violations committed by third-party contractors. Although RSPO standards clearly place the transport ferry that caused the 2014 tragedy under AgroPalma’s jurisdiction, the company was never reprimanded by either the RSPO or the state government of Pará for their negligent supply chain management.

It is irresponsible for public officials like Barbalho to blame these bridge collapses on infrastructure when a large share of the culpability should be attributed to corporate negligence by BioPalma and AgroPalma. However, it is equally irresponsible for the UNGC, the CHRB and RSPO to continue certifying BioPalma and AgroPalma’s supply chain management practices when they endanger the lives of local residents. In theory, certification schemes like RSPO provide Agropalma’s clients and consumers a benchmark to assuage their environmental and social concerns. In practice, companies like BioPalma and Agropalma carefully choose the different standards and certificates in which they participate.

Agropalma only works to obtain an environmental certificate when purchasers demand it. For example, Agropalma once considered obtaining certification from the Rainforest Alliance (RA) but opted out. Consumers, it seems, considered the RA certification “redundant” given AgroPalma’s RSPO environmental certifications. While the market value of RA approval may be minimal, the organization evaluates deforestation far more thoroughly than other certifying bodies such as the RSPO, which does not even use simple methods like remote sensing data analysis to verify the sustainability of their certified companies.

The RSPO also differentiates between areas with high forest cover (less than 80%) and low forest cover, thus giving members permission to deforest in areas where any more than 20% of the tree cover has previously been removed. Public records of AgroPalma’s “zero-deforestation” status are almost exclusively published by AgroPalma itself and are based on standards established by the RSPO and its affiliates (namely, the Palm Oil Innovation Group). It seems remarkable that AgroPalma has maintained its “zero-deforestation” status under RSPO certification, especially considering the commercial farming industry contributed significantly to Pará’s 12% of the decline in rainforest cover between 2000 and 2017. It is important to note that AgroPalma is not the only palm oil producer in the region and there are other industries that contribute to this tree cover loss. Nonetheless, AgroPalma’s deforestation practices warrant much closer scrutiny than what the RSPO currently entails if Para’s Amazon rainforest is to be properly protected.

The lax nature of RSPO certification does not just impact deforestation by AgroPalma. There is a real reason to believe that the RSPO’s weak reporting framework permits AgroPalma to exploit their labor force. A team of researchers at the Federal University of Pará (UFPA) analyzed records from legal proceedings brought against AgroPalma by a small group of employees and were shocked to find that laborers are required to arrive at work at 3am and must spray pesticides on at least 20,000 square feet of land per day. “Women working on AgroPalma plantations complained that they had to fill at least three 60-kilogram sacks of palm fruit per day in order to be compensated for their work,” according to a forthcoming report produced by UFPA researchers Vania Araújo and Daniela Correa. While these standards are abusive and contrary to the fair trade practices that RSPO portends to support, RSPO gives AgroPalma full discretion over which land is chosen for review by the certifying body. Thus, AgroPalma can intentionally leave any areas or processes within their purview that breach RSPO policy unreported, without follow-up from RSPO.

Professor Nirvia Ravena, a specialist in environmental justice at UFPA’s Center for High Amazonian Studies (NAEA), also believes that AgroPalma’s land grabbing tactics further evince their questionable ethics. According to Ravena, small landowners in the Amazon are encouraged to rent their traditional subsistence farms to AgroPalma for 25 years at a time. Included in this land rental contract is a 25-year work contract—in other words, farmers essentially promise both to rent their land and to work for AgroPalma for a quarter-century. UFPA researchers have documented that companies like AgroPalma draw in farmers by promising them up to R$4,000 (US$1,000) per month in earnings from palm oil plantation work. Once the farmers sign the contracts, the companies trap the farmers in debt by providing them with large loans for mandatory palm oil farming supplies (seeds, fertilizer, etc.) that they cannot afford to pay back. According to Ravena, farmers are also “suffer[ing] from increased food insecurity since they can no longer eat the food that they produce.” She believes that the long term nature of these contracts—in addition to workers’ pitiful wages, land vulnerability, and food insecurity—may place the company in violation of United Nations statutes on modern slavery. Apparently, the RSPO did not take any of this information into account when they renewed AgroPalma’s certification this year.

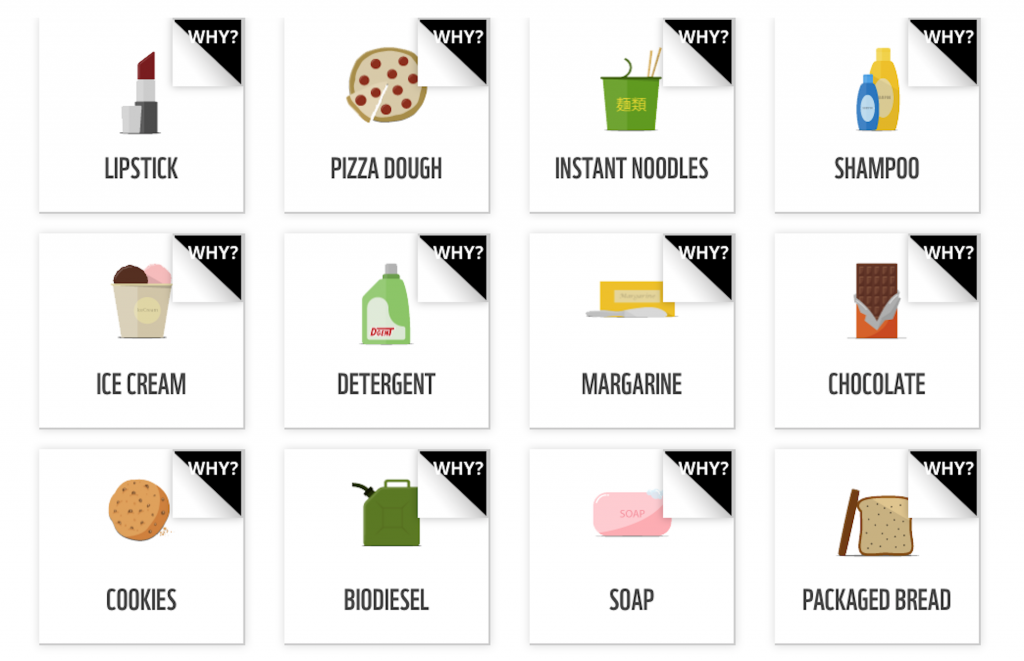

Despite the companies’ questionable ethical practices, the path to expansion looks extremely promising for AgroPalma and BioPalma in Brazil. In 2017, 236,000 hectares of land was used for palm oil cultivation in Brazil. Abrapalma, the body that represents palm oil producers in Brazil, predicts that this area will double by 2025. Global demand for palm oil has skyrocketed, and the market is expected to grow from US$65.73 billion in 2015 to US$92.84 billion by 2021. Large companies like Unilever, Mars, Nestle, FrieslandCampina, Colgate-Palmolive, ConAgra, Walmart, General Mills, Kellogg’s, and Danone all purchase from palm oil companies like AgroPalma and BioPalma that are certified by the RSPO. These companies directly cite sustainability certifications like RSPO as justification for the use of palm oil in a plethora of household products such as lipstick, pizza dough, ice cream, margarine, chocolate, packaged bread, and detergent.

Disasters like the Alça Viária bridge collapse indicate that international human rights certifications like UNGC, CHRB, and RSPO may provide a moral license for BioPalma, AgroPalma, and their peers to exploit traditional communities and natural resources in the Amazon while maintaining an ethical and sustainable facade for consumers. The companies can receive the backing of environmental NGOs like the WWF, which directly advise people to look for RSPO labels for “confidence that the palm oil was produced in a socially and environmentally responsible way” without being subject to rigorous—or even perfunctory—reviews of their sustainability practices. Consumers of palm oil and palm oil products, both on an industrial and a household level, deserve to know that these international organizations are failing to hold companies accountable. Companies like BioPalma and AgroPalma—and the rest of the palm oil industry in Brazil—must be pressured by the international community to improve social and environmental behaviors so the growing palm oil trade in the Amazon does not catalyze a human rights catastrophe.

Disasters like the Alça Viária bridge collapse indicate that international human rights certifications like UNGC, CHRB, and RSPO may provide a moral license for BioPalma, AgroPalma, and their peers to exploit traditional communities and natural resources in the Amazon while maintaining an ethical and sustainable facade for consumers. The companies can receive the backing of environmental NGOs like the WWF, which directly advise people to look for RSPO labels for “confidence that the palm oil was produced in a socially and environmentally responsible way” without being subject to rigorous—or even perfunctory—reviews of their sustainability practices. Consumers of palm oil and palm oil products, both on an industrial and a household level, deserve to know that these international organizations are failing to hold companies accountable. Companies like BioPalma and AgroPalma—and the rest of the palm oil industry in Brazil—must be pressured by the international community to improve social and environmental behaviors so the growing palm oil trade in the Amazon does not catalyze a human rights catastrophe.

Rachel Mucha is a Fulbright Scholar researching the intersections between natural resource management and gender parity in Brazil’s Atlantic Forest and the Amazon.