This is Part 3 of a three-part series on the History of Favela Upgrades in Rio. Click for Part 1 and Part 2.

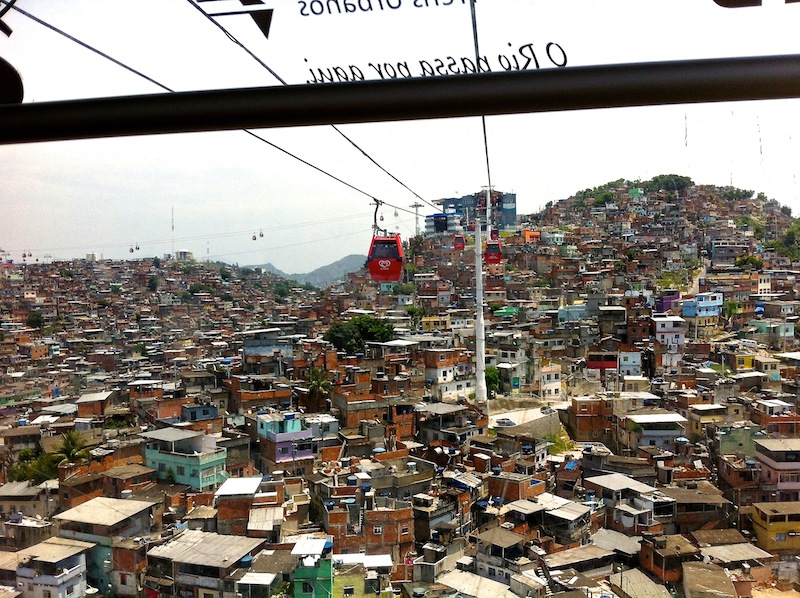

In Rio, the end of the 2000s brought a trickle of funding to a few delayed upgrading projects from the Favela-Bairro program and its spinoffs, the Bairrinho and Grandes Favelas programs. During this time the federal Growth Acceleration Program (PAC) began to install public works in favelas as well. These tended to be attention-grabbing projects and those visible from the edges of communities such as the cable car in Complexo de Alemão and the Oscar Niemeyer-designed bridge at the entrance to Rocinha, as well as some good examples of public housing and cultural facilities. That said, the need for quality and comprehensive public services in Rio’s favelas continued to far outweigh supply.

With this, Mayor Eduardo Paes made a bold announcement in July 2010, that as part of the social legacy of the 2016 Olympics, all of the favelas in Rio would be upgraded by 2020 through a municipal program called Morar Carioca. The program would have an R$8 billion budget and a partnership with the Brazilian Institute of Architects (IAB), who, as was the case with Morar Carioca’s predecessor, Favela-Bairro, would be responsible for arranging the upgrades in all favelas with over 100 homes. The number of favelas and complexes of favelas in the city was remanaged to facilitate grouping and upgrading under Morar Carioca, from 1020 to 625.

The specific budget and timeline of the Morar Carioca program have never been published in their entirety but rather have been alluded to in bits over the past few years. In November 2010 Mayor Paes named a budget of R$9 billion for the project and said he would finance it in three phases of R$3 billion each, with money coming from the city budget, credit from the federal government, and loans from the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), saying, “our idea is that the IDB enter with R$300 million per year for five years.”

Despite discussions of the program beginning two years prior, the official guidelines for Morar Carioca were only published in a document signed into city decree on October 29, 2012.

Morar Carioca on Paper

Morar Carioca is designed to build on the learning of the Favela-Bairro program and continue its work. In some of the literature about the IDB’s US$150 million loan for the project it is referred to as “Favela Bairro Phase III.” Learning from Favela-Bairro’s strengths and weaknesses, Morar Carioca pledges to carry out large-scale upgrading (public works to improve water and sewerage services, drainage systems, road surfacing, street lighting, the provision of green areas, sports fields, recreational areas, and the construction and equipping of social service centers), plus land titling and social services such as education and health centers in favelas. According to its precepts, Morar Carioca will reach 815 favelas listed by name, and is budgeted at R$8 billion, in comparison with Favela-Bairro which totaled R$1.2 billion between its two phases, and the interventions proposed in each favela will be more extensive and tailored.

Morar Carioca guarantees the right to “the participation of organized society…in all stages of Morar Carioca through assemblies and meetings in the communities” and through the “presentation of works and debates open to the participation of civil society and citizens.” It pledges to reduce the surface area of favelas in the city by five percent, remove homes that lie in areas of environmental risk, and follow legal guidelines to rehouse those residents near their original homes. Finally, it pledges to implement new zoning regulations for each favela once upgraded, transforming each into an “Area of Special Social Interest” (AEIS), based on the federal “Special Zones of Social Interest” (ZEIS) in accordance with the federal Statute of Cities passed in 2001 that established these areas in order to secure their continued preservation as affordable housing.

The Morar Carioca decree begins by acknowledging explicitly that favelas developed as a solution to the absence of adequate public housing in the city: “the historic absence of housing policy made informal production and self-building the alternative through which the lowest income population attended to its housing needs, and that informality ceased being the exception and became instead the rule for the majority of this population.” Eduardo Paes, when mentioning the Morar Carioca program in a 2012 TED talk in Long Beach, California, said “favelas can be a solution.”

Morar Carioca concludes from past experiments upgrading favelas in Rio that, if upgraded in a participatory way, favela-style development is a valuable urban form for the city. It is a partial but nonetheless visionary answer to the question that planners around the world are asking: how are we going to deal with the third of humanity who will live in urban informal settlements by 2050?”

Morar Carioca in Practice

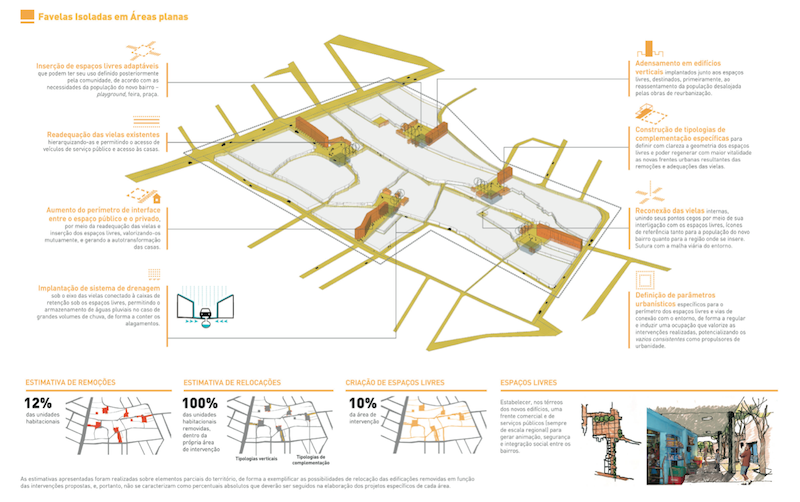

In accordance with its role in the Morar Carioca program, the IAB hosted a design competition in 2010 in which over eighty architecture firms from around the world presented sample designs for favela upgrading. Forty winning firms were chosen, and each was assigned a “grouping” of favelas to create plans specific to their topography, layout, and social service needs. In early 2011, municipal Housing Secretary Jorge Bittar said the goal was for all of these upgrades (set to reach 216 favelas listed here by architecture firm) to be complete by the World Cup in 2014.

Yet what followed was a waiting game where firms with the best of intentions, holding regular meetings amongst their teams to prepare to move forward, were left waiting until mid-2012 for resources to be released. At the same time, communities slated for upgrades were waiting, anxious and hopeful, for what were generally perceived to be positive and necessary investments that would occur in a potentially empowering way.

Once resources were freed for ten firms to begin in June 2012, they set to work. In accordance with Morar Carioca guidelines, all firms had a social worker or anthropologist on the team, committed to doing qualitative evaluations of the current use of public space in the communities. In addition, the NGO iBase was contracted by the City Housing Secretary to perform a “social diagnosis” that included focus groups, documentary filming, and individual door-to-door surveying about the improvements that residents thought were most important.

In late 2012, some plans were presented privately to City officials such as those from the Secretary of Housing and the Secretary of Transportation. Others were

As the year came to completion, communities participating in the program were hopeful. That said, there has been at least one reported case in which a community that was initially promised Morar Carioca upgrades and received iBase crews surveying them for community preferences and needs, were told instead that they face complete removal. In most others, after positive initial steps, residents were waiting excitedly, with no cases having broken ground as of March 2013.

Is it all Morar Carioca?

The Morar Carioca program has been very difficult for many people to pin down and understand because, though the decree and procedures are clearly delineated as described above, when the program was first announced in July 2010, Mayor Paes simultaneously announced that ‘Morar Carioca’ was already underway in fourteen favelas (quotes used when the program’s decree or other guiding documents are not being followed).

According to the Mayor, there are two phases of Morar Carioca upgrades underway in Rio. The first phase used firms contracted outside of the IAB competition to intervene structurally in favelas with no participation, in cases like Providência (where the works are currently halted by a court injunction due to a public defender’s charge of lack of public audience before the work began), Penha, Babilônia, and Jacarezinho. And the second phase, according to the Mayor, is that which formally only began in 2012, described in the previous section of this article.

“What a lot of people don’t realize is that the city government is using the label ‘Morar Carioca’ to refer to all sorts of upgrades that were not designed as part of this program,” says Mariana Cavalcanti, a Fundação Getúlio Vargas professor and anthropologist who was hired by one of the first architecture firms selected in the formal IAB competition. “They are using it to describe works going on in Borel and Chapéu Mangueira, for example, that were left over from the PAC years ago.”

Indeed, in many of the favelas identified by the Mayor as already undergoing ‘Morar Carioca’ in 2010, such as sections of Colônia Juliano Moreira, Mangueira, Manguinhos, and Guarabu, upgrades have been scheduled through the PAC for several years and will continue with PAC funding but under the new label of ‘Morar Carioca.’ Paes and IAB President Sergio Magalhães originally said all favelas with over 100 homes would fall under the official Morar Carioca program, receiving participatory upgrades designed through the IAB partnership, but the City has begun non-participatory interventions—even forced evictions—on several favelas fitting this description, including all those mentioned above. In the case of Providência, the construction crew has been using plans left over from the Favela-Bairro program, for which the only resident who gave an opinion was an informal representative of the Comando Vermelho, the drug trafficking faction that controlled the community at the time. And in Rio das Pedras, ‘Morar Carioca’ was announced when the sole outcome for residents would, in fact, be removal.

Morar Carioca Today

Morar Carioca was frequently mentioned during Eduardo Paes’ re-election campaign in October 2012, in which Paes said that 55 favelas had received Morar Carioca works so far and that the next step was to urbanize 100 more. He was referring solely to ‘his’ ‘Morar Carioca’, however, since no favela upgrades at that point had been done using the IAB-sanctioned participatory process. In fact, in January 2013 iBase’s contract to undertake the public consultation aspect of the IAB-selected upgrades was cut and since then several firms have been told to take down plaques claiming Morar Carioca is present in their communities. Needless to say leaders—and residents—of these communities are at a loss.

And while Morar Carioca as originally envisioned has barely been implemented—and has actually been stalled—so far, results can be gleaned for how upgrades, no matter the type, will impact Rio’s communities if not carefully implemented. One clear outcome has been the rapid rise in home prices, since the very important step of zoning these communities and establishing them as ZEIS—areas recognized and maintained as affordable housing—has not been carefully applied and even when it is applied, has not been capable of curtailing gentrification. Morar Carioca spokeswoman Sonia Lopes predicted this effect in an interview with an international investment guide in October 2010, when she said the program “will help keep the market for real estate strong whilst also creating new areas of opportunity.” For many favela residents, the consequence of this speculation is that they can no longer afford to live in their homes. Last month, in one favela in the Complexo de Alemão, which has received UPP police and PAC upgrades, the President of the Residents’ Association was priced out of her home along with 416 other families when rent rose over 300%. Community leaders and local academics refer to gentrification in favelas as a second kind of removal: “remoção branca,” or white removal.

Despite the incredible promise of Morar Carioca in theory—not only for Rio to engage in an inclusive form of sustainable urbanization, but for it to serve as a model of how to handle informal settlements in an increasingly urban world—in practice, the program’s name has been used so far by local authorities only to undertake authoritarian and unilateral, often arbitrary, interventions in Rio’s favelas. In the historic trajectory of “to remove or to upgrade,” the current City government has arrived at a third, contradictory path with Morar Carioca: a proclamation of upgrading but a practice that emphasizes home removals, both through overt demolition and enabling of gentrification.

References

Mello, Marco Antonio da Silva, Luiz Antonio Machado da Silva, Leticia de Luna Freire, and Soraya Silveira Simões, eds. Favelas cariocas: ontem e hoje. Rio de Janeiro: Garamond, 2012.

Perlman, Janice. Favela: Four Decades of Living on the Edge in Rio de Janeiro. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Morar Carioca charter document

List of favelas to receive Phase II Morar Carioca upgrades by architecture firm