For the original full post in Portuguese by Dodô Azevedo on G1 click here.

June 14, 2013

João do Rio, the famous nineteenth-century Carioca journalist and writer, used to say that to learn the facts one must go to the streets.

And so we did our homework. We accompanied the Rio march of Thursday June 13 against the rise in bus fares from beginning to end. But we also took with us the questions that every Carioca (Rio resident) is now asking himself regarding this movement–a movement that Spain´s El País, one of Europe’s biggest newspapers, compared to the already-traditional protests claiming people’s rights which have occurred over the rest of the continent for decades:

“Maybe from now on Brazil will have to get used to these street demonstrations that are so common in other countries,” wrote their correspondent Juan Arias.

Our blog came back with answers. The streets responded. They never fail. Let’s get to them.

The movement against the rise in bus fare is…?

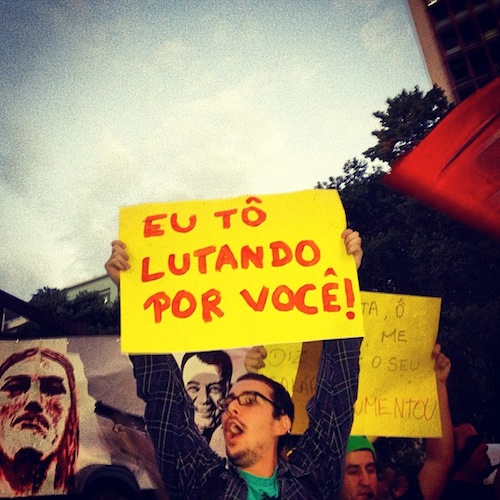

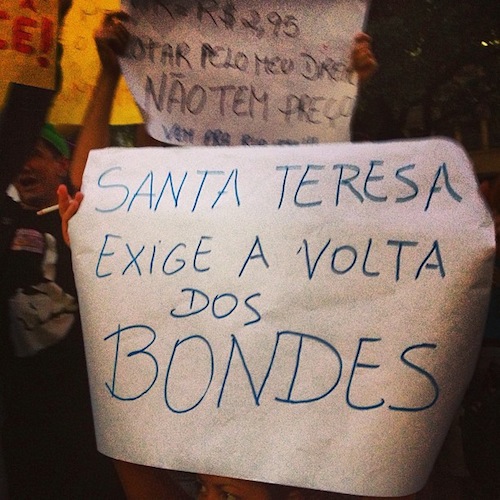

That´s how it started, but it’s not just a movement against the rise in bus fares anymore. That was the initial cause–and it’s still the official one–but in practice it merged with many other citizens’ demands regarding a range of issues: from the return of the Santa Teresa trams to the lack of transparency in public spending on the Engenhão and Maracanã stadiums, to the abolition of the “PEC 32”, a potential constitutional amendment that excludes the right of investigation and inquiries by prosecutors in federal and state bodies. While each group has a specific demand, everyone agrees with others’ demands. It´s become an opportunity for citizens to go to the streets and protest against an accumulation of problems, scandals and calamities that are reported every day.

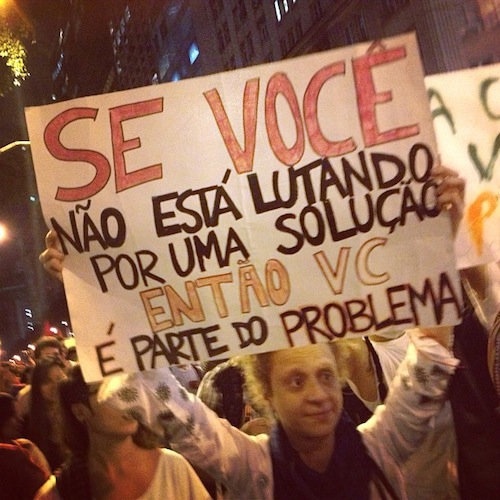

Is the movement–which we will call a “movement against the current state of things in this country”–affiliated with any party?

At the onset, yes, but since last week’s protests, no. This is, first of all, because people are slowly acknowledging that “all parties are the same,” and second, because different problems are the responsibility of different parties. As a result, dissatisfied voters and citizens, regardless of the party they support, came together to protest. It became, thus, a movement against bad politics.

Is the movement against Mayor Eduardo Paes and Governor Sérgio Cabral? Is it against President Dilma?

Yes and no—it’s against all those currently in power. There is a general consensus that nobody is administering their duties well these days, and this is heard both on the streets and online. From the posters that are being shown in the crowds, one notices that there is also a more sophisticated understanding that the problem is not exactly with Dilma, the PT (Workers’ Party), Lula, the PSDB (Social Democrats’ Party), Fernando Henrique [Cardoso] or Sarney. There’s a kind of accumulated awareness of all of the governments’ wrongdoings in the last 60 years and a desire to clean things up, past and present, or at least an uncontrollable impulse of running to the streets and crying that we can’t take the filth anymore. In a conversation with older demonstrators at the march, most in their 40s and 50s, we heard people recognizing this outbreak as a sign of progress and maturity in our democracy.

40 and 50 year olds? Which segments of society are taking part in this movement?

Most are very young, between the ages of 17 and 27. It’s a big group made up of smaller groups. At the gathering at the beginning of the march, the arrival of each new group was met with celebration by the others. The uniformed students from Colégio Pedro II federal school were cheered the most. They are energetic. We saw one finish a bottle of mineral water and walk 100 meters to dispense the empty bottle in the trashcan.

Are they really that young? So is it safe to say that the Facebook Generation has finally decided to put their “sofa activism” aside and go to the streets?

Not at all. This new youth doesn’t think the virtual reality limits the actual one; they have learned how to live both “lives” from a very early age. In other words, they don’t treat the “actual” and the “virtual” as opposites. It is us, the older ones, who have that impression. Like the adults of our generation that swore the invention of TV would be the end of cinema.

Are the demonstrators vandals?

During last week´s demonstration, some 2% were, yes. Those were anarcho-punk youth groups that stand against political parties and the government and support anarchism. They are rebels full of causes and, yes, they are proud to be vandals; after all, that’s the basic principle of real anarcho-punks, be it in London, New York, wherever. The other 98% of demonstrators are not vandals, and they rebuked those who tried to destroy public telephones and scribble on bus stops. In some cases, they even managed to talk aggressors out of their vandalism. Other demonstrators accept that history “cannot be made” without shattering some glass, and that goes back to before the Bastille. And there are even those who prefer making their own rules to follow; for instance, landmarks like the Municipal Theater, which stands close to the march’s itinerary, should be respected, but the Rio Forum, home to Rio’s Court of Justice, not really, no.

What was the general reaction to the march and how did it affect the mobility of those working downtown?

There was tension when it began. However, because the march grew bigger than previous ones, and as more people joined the crowd simply out of empathy, vendors and passersby began applauding the demonstration as it moved down Rio Branco Avenue. Storeowners, taken by surprise, soon realized the demonstration was peaceful and decided to remain open throughout the day. On Rio Branco Avenue near the cross-section with 7 de Setembro Street, office workers threw confetti-like paper from their windows to greet demonstrators—yet another sign that discontent is everywhere.

About those in power now, then: Governor Sérgio Cabral said these demonstrations are orchestrated. Is it true?

They are as orchestrated as the mobilization for the oil royalties that was organized by the Governor himself, our Mayor and some artists. As orchestrated as the Rock in Rio event. As orchestrated as going out for dinner or to the movies. You create a Facebook page and invite people through there, and there are announcements at the marches themselves about when the next one will be.

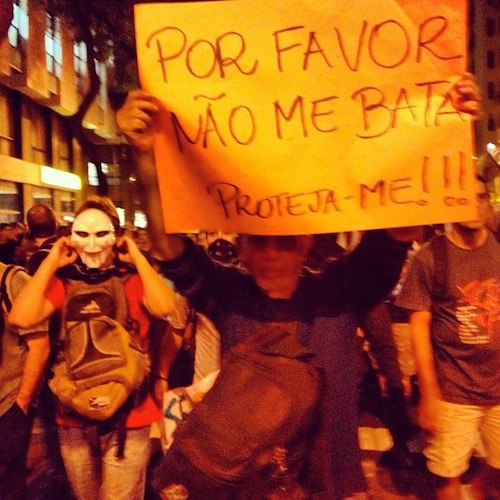

How did the Military Police of Rio State react to the demonstration as it was happening?

They were surprisingly moderate. The media was curious to see which side would initiate conflict, the police or the demonstrators. The Military Police followed the entire event without directly imposing anything, leaving it to the demonstrators to decide on how the movement would evolve. There wasn’t tension between the groups, no intimidation or provocation from either side. In reality, it was the demonstrators themselves who threw the small number of teargas bombs that were set off, the anarcho-punk minority in particular. But to everyone’s surprise, the police did not react. Only when we had reached the Legislative Assembly (ALERJ) and 90% of the people had left, did these small groups run to Presidente Vargas Avenue with the explicit purpose of causing trouble with the police. At that moment, it was pretty violent. Those were the images that were filmed by helicopters and publicized by the Jornal Nacional TV channel. If you’d seen it from up close, you’d agree it was a small conflict compared to what happens between soccer rivals and the police after a game.

Is anyone leading the movement? Important slogans or battle cries?

No, there isn’t one specific group or person taking leadership, at least not deliberately, and this is a common feature among the political movements of the 21st century. The message they want to send out is that the movement is embodying people’s voices, and not showcasing faces. Battle cries? Yes. Down with the government, with the mayor, with the media and the powerful—all of the cries that have flooded every protest throughout history. What’s new is that it’s not just about a 10-cent rise in bus fares anymore, as the following battle cry evidences:

“This isn’t Turkey, this isn’t Greece… this is Brazil stepping out of its inertia!”

Following the event’s reporting, which was running smoothly, we overheard an Argentine reporter say to his Brazilian friends that “it was about time,” and that “in places like Berlin, New York, Paris–in any civilized country, really–people would have long fired the city in response to even half of the scandals that go on in Brazil.” He mentioned how the similar waves of sexual assaults in Brazil and India saw different reactions: while in India there were millions in the streets, putting fire to entire cities demanding justice, in Brazil nothing happened.

It seems as though the situation in Rio is not as apocalyptic as it appears. So is joining the movement recommended?

If the government decides to reduce the bus fares back to what they were before, part of the movement’s most articulated demonstrators will settle back and perhaps dissolve. Otherwise, these marches will quickly become a mass movement. There might soon be casualties. Maybe soon few people will remember that it all began with the bus fare rise, and the greater movement will have already been given a name. The Brazilian Winter? Who knows. Yesterday’s protest was almost sweet. But that sweet that reaches our nostrils, five seconds of sweetness before discovering that, in truth, what I’d experienced was pepper spray.

Winter begins in one week.

And its end is not in the forecast.