On Thursday June 20th, over 300,000 Rio residents marched down Avenida Presidente Vargas, draped in Brazil flags and chanting for improved education, health, transport, and an end to corruption, evictions and overspending on mega-events. The act constituted a powerful collective demand for a better Brazil and was a beautiful, historic moment of civic pride in Rio.

But just a few hours later, as one Carioca posted on Facebook: “The love’s over. It’s turned into hell.”

For tens of thousands of peaceful protesters in Rio, the hours following the protest were indeed a hellish ordeal. Trapped in Rio’s downtown as roads were closed and Metro stations shut, citizens who’d come out to exercise their democratic, constitutionally protected right to protest found themselves indiscriminately shot at and tear gassed by Rio’s military police forces in a repressive operation that spread across the entire central region of the city.

The “madness,” as many witnesses euphemistically called it, started when the crowd arrived at the march’s destination, City Hall. Between 7 and 7:30pm a conflict broke out between police and a tiny group of demonstrators out to cause trouble, throwing rocks at police, destroying and vandalizing public property and setting fires in the street. Police responded to this minority by firing tear gas bombs, pepper spray, rubber bullets and concussion grenades towards the crowd. This much has been well documented by mainstream media. But the shocking experience of the majority of those caught in the police firing line–non-violent protesters and innocent bystanders–has only been widely documented and discussed on social media.

“I was a victim of police terror and torture tonight. The sensation of tear gas in your face, amidst people who didn’t know what was happening and cried and ran and screamed ‘I’m going to die!’ can only be described as terror and torture,” wrote one protester. Another posted: “What we saw today was a planned act of terrorism against all of us. We were CORNERED by an extremely unprepared and fascist police force. The streets of downtown were taken over by men dressed in black.” Yet another citizen wrote: “I can’t believe what I saw today! They surrounded many protesters, trapping them… they threw tear gas inside the Pizzaria Guanabara in Lapa, even with families eating and children… pepper spray inside a bus.” One simply put, “We’ve gone back in time [to the] dictatorship! I’m shocked by all this!”

Around 400 demonstrators took refuge at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro’s Institute of Philosophy and Social Sciences (IFCS), where they were surrounded by police and unable to leave. The group was escaping the police action that had taken over Centro and then became terrified to go back out. Representatives from the Brazilian Lawyers´ Association (OAB) assisted the group to eventually leave. Vice-president of the OAB in Rio de Janeiro, Ronaldo Cramer, said: ¨The situation at IFCS was sad. Students were under siege, scared to leave because they were afraid they´d be persecuted.¨

The following day, the Institute released a statement saying, “We must all be concerned that the State comes to adopt an aggressive and intolerant position, treating citizens as enemies and persecuting them in the streets, as was observed and experienced by many during that long, hard night.”

One of the most shocking reports of police brutality in the hours following the protest came from staff and patients at the Souza Aguiar Municipal Hospital where those injured in the post-demonstration conflict were being treated. Police fired rubber bullets and tear gas bombs inside the hospital, where the gas was reported to be felt as high as the seventh floor. One doctor at the hospital posted: “Half a dozen demonstrators were asking the police not to shoot because it’s a HOSPITAL, and even so, the unprepared police officer positioned himself, aimed and fired two bombs! My God what is this?! The people there are ILL!”

Accounts, photos and videos on social media give a sense of the scale of the operation with reports of repressive and violent police activity from as far north as Praça da Bandeira to Laranjeiras in South Zone, lasting well into the early hours of Friday morning. Over 7,500 armed police units were deployed utilizing tanks, horses and dogs and setting off over 2,000 tear gas bombs, many found to be out of date. Reports and videos show that street lighting was shut off in Centro for extended periods. All five of the central Metro stations were shut leaving those desperate to go home without recourse and in the line of fire, and at one point the images from the IBM Operations Center–Rio’s new high-tech center coordinating 30 agencies–camera on Avenida President Vargas were subsituted with images of traffic in Barra da Tijuca. There was even one report on Facebook from someone who overheard a Globo reporter talking earlier in the day about covering the protest that night, and that “confusion will erupt only at 9:30pm, and so until then it will be calm.”

That innocent bystanders and non-violent protesters were deliberately under attack for hours, in the dark, and denied access to public transportation in order to leave raises grave questions about Rio’s crowd management strategy and seriously undermines the credibility of police claims that “the Military Police has the purpose of maintaining a basic principle of democracy: peaceful coexistence.”

That innocent bystanders and non-violent protesters were deliberately under attack for hours, in the dark, and denied access to public transportation in order to leave raises grave questions about Rio’s crowd management strategy and seriously undermines the credibility of police claims that “the Military Police has the purpose of maintaining a basic principle of democracy: peaceful coexistence.”

Policing a mass demonstration is a tough challenge for any law enforcement agency and operations are often open to criticism. Research by police agencies recognizes this challenge and provides insights into how the situation can best be managed. The International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) and the Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) in their report Managing Mega Events: Best Practices from the Field emphasize a relational approach, active communication with protesters and riot gear as a last resort. The findings are reiterated in the US Federal Bureau of Investigation’s report of last year, Crowd Management: Adopting a New Paradigm, which stresses constructive dialogue as a primary tactical option, saying, “Communicating expectations, negotiating continually, and emphasizing the goal of safety are vital. Officers should not confuse the actions of a few with those of the group.”

The FBI report also advises against the use of excessive force: “When a crowd becomes unruly and individuals perceive unfair treatment by law enforcement officers, violence can escalate, and a riot can erupt. Recent research […] concludes that when police officers act with legitimacy, disorder becomes less likely because citizens will trust and support law enforcement efforts and behave appropriately.”

Crowd psychology expert Professor Steve Reicher corroborates this view, saying in a BBC report this week that “the balance of voices within a heterogeneous crowd is affected by the relationship between the crowd and the police,” and further, “under conditions where the crowd is treated as all the same, and all dangerous, the crowd changes.” Certainly in RioOnWatch’s experience of Thursday night, the destructive behavior of a few intensified greatly immediately following an attack on the crowd by police.

All this begs the question, to what extent were police forces attempting to incite, rather than contain, destructive behavior following the demonstration on Thursday evening? How planned out were the operations and is it really possible that reporters knew ahead of time? Were police forces working to intentionally delegitimize the protest’s historic numbers? Were police forces actively trying to punish protesters and discourage participation in future demonstrations?

The Rio Military Police justifies the use of force in its operations based on the elimination of a perceived enemy. At Thursday night’s protest, in theory that enemy was the group of vandals destroying public property. A great spectacle is needed to create legitimacy for such excessive force among the population. A small group of vandals doesn’t constitute such a threat. So as the thousands of protesters trapped in Centro struggled to escape the apocalyptic nightmare of being fired at by a police force that claims to protect them, millions of television viewers watched a seemingly relentless stream of shocking images of vandalism captured by Globo TV helicopters circling the area. Newspapers on Friday led with this same story in which the destruction of property became the main narrative of the night, neglecting to account the experience of a record-high number of peaceful protestors united in their indignation and providing justification rather than scrutiny of the police use of force.

The following morning Mayor Eduardo Paes released a statement saying: “The vandalism…was a very clear demonstration that a minority exists which unfortunately protagonizes these acts. These people are, above all, undemocratic. People who act like this don’t know how to live under the rule of law, where citizens have every right to protest.”

Though the Mayor was referring to those who had committed acts of vandalism against public property, in the experience of peaceful demonstrators and innocent bystanders who suffered from the extreme police violence, the undemocratic protagonist of these events in Rio de Janeiro were not the few vandals but rather the State’s Military Police. Since last week the word “vandalism” has been widely used by Rio’s citizens on social media in reference to the State’s actions.

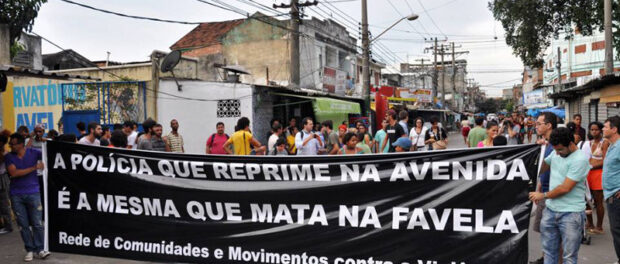

With the middle class experiencing the horror of being indiscriminately cast as an enemy of Rio’s police last Thursday, and the death of nine people in an extremely violent police operation in Maré over the last few days, the case for the abolition of Brazil’s Military Police gains significant ground. One favela resident who protested at Thursday’s event posted: “Now do you all understand why those who live in favelas hate when the police come in and even preferred they never come? Now can you imagine what those Military Police officers DID? The atrocities they committed? If in front of cameras and the media they do what they do, imagine against blacks, poor, favela residents, without media?”

Amnesty International has launched a campaign urging people to email or tweet authorities requesting that police act in a way that respects the right to freedom of expression and not abuse police power using tear gas and firearms. For more information click here.

Approximately 500 social media posts by protesters within our network were consulted in the preparation of this article.