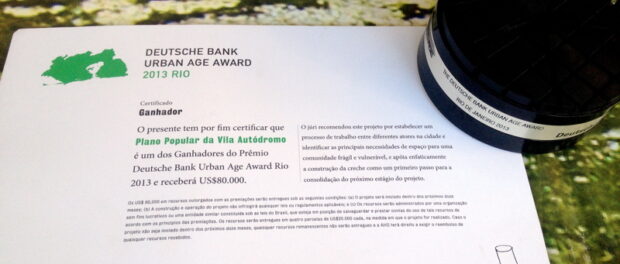

“Receiving this international prize honors and rewards us in our struggle for the right to the city,” stated Luiz Cláudio da Silva, a 19-year resident of Vila Autódromo, upon hearing the news that the Vila Autódromo People’s Plan to upgrade the community had won the prestigious Deutsche Bank Urban Age Award, chosen from among 170 Rio de Janeiro-based community projects. The award, in addition to granting a much-needed monetary investment of $80,000, recognizes and validates Vila Autódromo’s ongoing struggle to remain in the face of mounting pressure from the City.

Within a tense political climate, the international jury issued a symbolic critique of the Olympic project and the way it is utilized to justify removals. One jury member, Paola Berenstein Jacques, an architect and urbanist at the Federal University of Bahia, put it simply: It was a decision “in favor of resistance and against the removals taking place in Rio de Janeiro.” Carlos Vainer, an urbanist at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) who helped coordinate the project, called this victory for Vila Autódromo “a defeat to the elitist Olympic project of the Rio de Janeiro government.”

The Deutsche Bank Urban Age Award was created in partnership with the London School of Economics, “to encourage people to take responsibility for their cities” and is given to projects that “improve the physical conditions of their communities and the lives of their residents.” Although the award ceremony was originally scheduled to coincide with the LSE Cities Urban Age conference in late October, the announcement of the winner was postponed suspiciously and without explanation.

Rumors circulated that the short-listed Vila Autódromo People’s Plan had won, and that the Mayor had cancelled the ceremony rather than present the award to the community, a gesture that would have effectively legitimized Vila Autódromo’s struggle to remain. “We understood it that the Mayor cancelled the award ceremony because we were the winners,” Inalva Mendes Brito, another longtime Vila Autódromo resident and activist explained. “If it was another community, it wouldn’t have been delayed.”

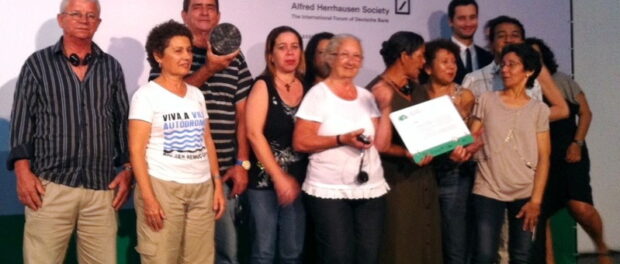

Finally, on the evening of Tuesday, December 3, the Vila Autódromo People’s Plan was officially presented with this international honor at the Institute of Brazilian Architects. During the cocktail party and live music, Luiz Cláudio described an emotional experience: “It is hard to describe in words that feeling when it seems like your heart wants to jump out of your chest. It was and is still, exciting for all of us.”

The Urban Age Award includes a prize of $80,000 to begin implementation of the upgrading plan. When asked about how the money will be directed, Luiz Cláudio responded: “Of course our priorities are numerous, having been abandoned by the government for decades.” He continued, “We have not changed our old dream of establishing a daycare center in our community.”

“This award raised our self-esteem by recognizing our struggle for the right to housing and to the city,” Inalva Mendes Brito explained. The recognition “reaffirmed our honor and dignity as citizens with rights,” adding that these rights that have often been disrespected and ignored by the City and the local media.

One jury member, Lívia Flores, an artist and professor at the Rio de Janeiro Federal University’s School of Communication, expressed concern for the community’s future, given not only the recent blocking of free information about the award, but also because of “the aggressive policy of the state and the magnitude of economic interests involved.” She and other jury members expressed hope that the award would bring recognition of the community’s rights and “help support a pioneering experience of self-management and resistance to an exclusionary policy of removals.”

The Jury’s Decision

A jury of urban experts—hailing from Brazilian and international academic and cultural institutions—considered 170 Rio de Janeiro-based projects for the prestigious award. One jury member, Paola Berenstein Jacques, was explicit about the symbolic and political possibilities of the award: within the context of massive transformations underway in Rio de Janeiro–including the “violent urban processes” of real estate speculation, forced removals, and gentrification–she and other jury members understood the award as an opportunity to “encourage projects of resistance that are critical of these processes of segregation.” She continued that the jury decided to support projects and people working to “problematize the issues of spectacularization, commodification, and privatization of cities and urban services,” themes which manifested in protests this year throughout the country.

During initial discussions, the People’s Plan was thought to be ineligible because one of the criteria was to have already started implementation. Lívia Flores explained that she and other jurists knew the history of the community’s struggle and challenged that resisting removal by proposing an alternative plan was evidence of “implementation,” even without physical construction.

After extensive deliberation including on-site visits to the projects in late September, the jury selected the Vila Autódromo People’s Plan based on assessments of “the viability of its implementation and urbanistic considerations” as well as “the symbolic significance of the award within the political context of the city,” according to Lívia Flores.

Ms. Flores cited several key characteristics of the Plan that influenced her decision as a member of the jury: “Self-management capacity, seeking partnerships and improved living conditions, claiming the right to the city and to citizenship, maintaining ties and community memory, resistance to the City’s removal policy […] affirming the right to the territory based on documentation.”

The Plan

The Vila Autódromo People’s Plan–calling for the urban, economic, and cultural development of this long-neglected community–represents one of many efforts to resist “an unjust, unjustifiable, and illegal removal attempt.” Through a collaborative and participatory process that brought together the community, Neighborhood Association, and the technical planning team from two public universities (UFF and UFRJ), the Plan stands as a cost-effective and dignified alternative to forced removal. Professor Jacques described the “beautiful partnership” between the community and two public universities as a model that “should be welcomed and encouraged throughout the country.”

“The residents show a new way of constructing a democratic city,” reads the People’s Plan in its opening pages. “This time, the politicians, businessmen, public-private partnerships, or the City technocrats are not the ones to determine the community’s destiny. Instead, the population, that lives with the day-to-day realities and difficulties, determines what is necessary and how it should be done.” The project defines priorities and proposes solutions related to housing, sanitation and urban infrastructure, public transport, education, and cultural programs.

Conclusion

The Vila Autódromo People’s Plan has become, in Paola Berenstein Jacques’ words, “the icon of resistance to the Olympic project in Rio de Janeiro.” The implications of this prestigious international recognition extend beyond the financial support of the prize or the frustration with the politicized postponement of the ceremony.

The victory of the Plan represents a challenge to what Paola Berenstein Jacques calls “hegemonic urbanism,” a series of urban planning practices (including mega-event staging) that increasingly favor the “corporate, spectacular, flexible, and neo-liberal.” She argues that this “hegemonic urbanism” is created by “false consensus” and designed to avoid conflict. “In direct response, we begin to see clear forms of resistance emerge,” she said, citing the historic demonstrations in June and the surge of rebellions that brought people to the streets. These examples of “conflictual urbanism” reflect a broader struggle for the right to the city.

“This is not just a victory for the community of Vila Autódromo,” Luiz Cláudio concluded. “It is a victory for all communities living in similar situations and all those engaged in the struggle for citizenship and social justice.”