Rio’s Most Brutal Eviction “For the World Cup”

The World Cup is well underway, and in Rio the games are being played in the Maracanã Stadium just around the corner from what used to be the Favela do Metrô. But Metrô has not been transformed into a parking lot for the Maracanã or a commercial strip with mechanic shop complex and park, the City government’s rumored intentions. It hasn’t been transformed into anything at all.

It has now been four years since Favela do Metrô, also known as Metrô-Mangueira, was first threatened by City authorities. The community was the first to gain international visibility for the harshness of its eviction process back in 2011. RioOnWatch has followed the longwinded situation in Metrô since the initial demolitions in November 2010, residents’ subsequent resistance to worsening living conditions, the outcome for those moved far away, ongoing difficulties as residents living amongst the rubble awaited housing, and the violent eviction of those squatting in the area in January of this year.

From functioning community to rubble

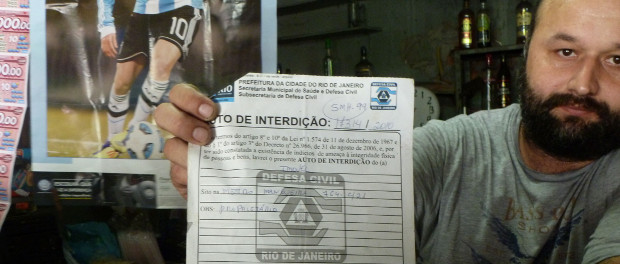

In November 2010 when demolitions began, 700 families called Favela do Metrô home. Only a few months ago–over three years later–were all the remaining homes demolished, leaving heaps of rubble, garbage, children’s toys, and pieces of furniture piled up in now-vacant lots. RioOnWatch caught up with Eomar Freitas, one of the last residents to leave Metrô. With a bushy black beard and twinkling eyes, Eomar spoke from behind the counter of his tiny bar. His is one of the last botecos in an area that used to have 12 bars and 126 small businesses.

After the first round of demolitions, scattered sporadically throughout the community, living conditions in Metrô rapidly deteriorated. Describing what it was like to live in Metrô during the long process of removals and demolitions Eomar said: “We [my mother and I] would be trying to sleep, and meanwhile the city government workers would be demolishing the houses right next door. The situation here became precarious–we started having robberies, and drug users began to arrive.” Eomar added drily, “You know how people talk about Sex, Drugs, and Rock ‘n Roll’? That’s what we had: Sex and Drugs–minus the Rock ‘n Roll.”

Besides the new presence of drug users, prostitutes and homeless, Metrô’s demolished buildings soon harbored infestations of rats and dengue-carrying mosquitos. The City government stopped collecting trash altogether, making conditions increasingly hard to bear for those who wanted to stay. As conditions worsened, city officials cited the very health reasons that initial demolitions had created as a way to justify further removals.

This past January saw the most recent spate of removals, with hundreds of people who had been squatting in half-demolished properties violently evicted by the police. Making international news, the police used rubber bullets, pepper spray, tear gas, and flash bombs during the eviction; no explanation or recourse was offered. Despite Mayor Eduardo Paes’ in-person promise that no one from Metrô would be left homeless, those evicted this past January were left with no prospect of resettlement or compensation.

Life in new public housing

Between 2010 and 2014, different stages of resistance and removals resulted in vastly different outcomes. Those who resisted longest received the best offers from the government, with the last original residents like Eomar and his mother getting resettled in the nearby Mangueira 1 and 2 public housing, originally designed for higher income bracket residents. In contrast, those who were the first to leave, mostly elderly people, were resettled in the West Zone neighborhood Cosmos, 2 hours or 75km away.

While securing resettlement in Mangueira 1 and 2 underlines the efficacy of resistance to removals, many are unhappy with both the lack of community and financial burden of living there. Asked whether he would prefer his old house to his current living situation in government housing, Eomar didn’t hesitate: “I would prefer my house. Because my house had a balcony, we used to have people over for barbeques… My house was ugly. It was. But it was mine. And I still can’t say that about the public housing.”

In Mangueira 1 and 2 the government is charging R$99 (US$44) per month for rent and water, and the bills for electricity and gas add additional costs. The total cost of living is twice as high as it was in the favela, and according to Eomar, “a lot of people are struggling to pay the bills.”

Watching the soccer game from a small table, one of the bar’s few customers chimed in. He explained how, despite the higher costs, people are generally frustrated with the poor quality of construction in Mangueira 1 and 2. “The floor is like the one here [pointing to the bar’s slate-grey tiles], except there, if you try to take part of it up, the whole thing peels off. People are afraid to put nails in the wall because they might go through.” The 40-square-meter apartments are smaller than many residents’ former homes in the favela. Asked how his current situation compared to his old house in Metrô, all he had to say was, “it’s worse.” Hardly a heartening response, especially since this is some of Rio’s best public housing.

No transparency over eviction motives

One might assume the government must have a very good reason for trying so hard to remove the Favela do Metrô. But the City has never offered a consistent explanation for these removals, instead making conflicting promises over the past four years. The most persistent rumor was that the government wanted to turn Metrô into a parking lot for the Maracanã Stadium for the World Cup. Eomar related, “We’ve heard so many stories. We kept hearing that the removals were in order to build a car park for the stadium. But it was never certain. It was always just rumors.”

Beginning last week, government-contracted workers started work on the far edge of Metrô. Once again, small business owners and former residents have not been informed about this new construction. When approached, one of the workers said the area is indeed going to be a “parking lot for the Olympics.” This contradicts the Municipal decree of September last year declaring the area would become a mechanic shop complex and park area. This latest change of story reflects the government’s unwillingness to admit that as of now it has nothing to show for some of the most inhumane removals the city has seen in recent years.

The construction crew in Metrô represents just a fraction of 2,000 people employed by the City to carry out demolitions and construction on behalf of the City government. Many of these workers live in favelas themselves. Asked how he felt about carrying out demolition against residents’ wishes, one worker responded, “é constrangedor,” a feeling akin to ‘uneasy’ and ‘ashamed.’

Pressure on businesses to leave

On the other side of Metrô, the owners of the remaining businesses, mostly auto parts shops and mechanics, are doing their best to stay open. For Eomar, business is “down by 95 percent,” because his customers were the residents of Metrô, and other business owners are not faring much better. Though the municipal decree on space usage in Metrô confirms the right for these mechanic shops to stay on as part of a smaller “Parque Linear Automotivo Metrô-Mangueira” (automotive park), the City government is actively trying to push businesses out. Every day, a city official comes to issue tickets to all shop owners that are servicing cars parked on the street. These tickets range from R$85, if paid immediately, to R$127-130, if challenged.

Eomar shared his own experience with this new tactic. At one point during demolitions, debris had been falling on his car, so he moved it to the street; he was promptly fined and ticketed. For business owners that are already dealing with plummeting revenues and more expensive housing, these tickets pose a serious threat to their long-term ability to stay afloat.

Before we left, Eomar gestured toward the two football posters hanging behind him: Portugal’s Cristiano Ronaldo and Argentina’s Lionel Messi, with no Brazilian players or team colors to be seen. “This is how I feel about the World Cup.”

Eomar had one final, chilling observation to make. “So essentially, all the people who lived here, the residents, were worth less than a parking lot.” A parking lot that, going into the second week of the World Cup, has not even been built.