After decades of fighting for the right to stay on their inherited land, Quilombo Sacopã was recognized by the federal government this Tuesday September 23. Sacopã is the first urban quilombo to be recognized by the federal government in the state of Rio and is located in Lagoa, one of the most expensive neighborhoods in the city.

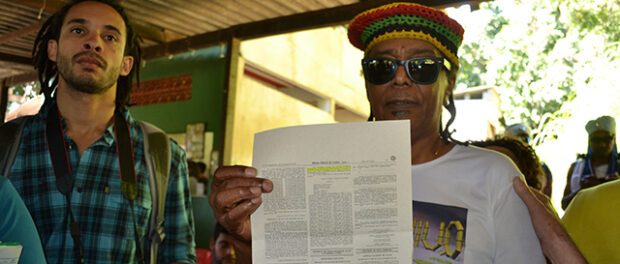

Luiz Pinto, leader of the community and president of the Quilombo Association of Rio de Janeiro State (AQUILERJ), received the document that guarantees ownership of the 7,000 m2 parcel and celebrated with his community and members of over 20 quilombos who came to witness the historic event.

Quilombo Cruzeirinho, from the city of Natividade, also received their Technical Report of Identification and Delimitation (RTID) which is the first step to gaining their land title.

The community of Quilombo Sacopã has lived in the area for over a century, but has suffered numerous attempts of forced removals and buy-outs. In 1999, the community officially gained quilombo status, in accordance with the 1988 Brazilian Constitution that determined that descendants of slaves would gain rights to the land they had historically occupied as a means of reparations.

After acquiring quilombo status, the 28 people inhabiting Sacopã had to wait 15 years until they could receive official ownership of their home and federal recognition. There have been constant conflicts between the residents of the quilombo and the wealthy residents of the surrounding buildings.

The ceremony took place in the event space of the community and included cultural performances from the Afro-Brazilian group Afoxé Filhos de Gandhy.

“The stigma of racial segregation still impregnates a part of Brazilian society. But today, it is being proved that even with the force of real estate speculation, with its economic power and its power of influence along with the rotten judiciary–they lost,” Luiz said to a cheering crowd, before receiving the document. “Today, excitedly, I can tell you that I was born on this land, I took my first steps here. Today I am 72 years old and I can say it’s a historical day for our country.”

“Today we have the certainty that the path we have taken, my people, is working and there is nothing better than this quilombo, surrounded by upper class luxury condominiums. We resisted and we won. Today is a day I can claim: I was born here, I was raised here and here I will die.”

In a note to the press, the Institute of Colonization and Agrarian Reform (Incra) said: “The recognition [of Quilombo Sacopã] is the last step before the definitive titling, when the ownership of the land will be registered in the name of the community, which will not be able to sell, rent or get rid of the area. This recognition means that the quilombola territory has received their final delimitation, which gives definitive judiciary security to the community since all the phases of protestation have already expired.”

Feijoada & Heritage

The quilombo served feijoada to its guests, the Brazilian national dish, widely assumed to have heavy African influences. The food was fitting because Sacopã was forbidden from hosting their weekly feijoada and samba cultural events by the former mayor César Maia. This disrupted the community’s right to express their Afro-Brazilian culture and earn money to support themselves.

“César Maia came here and put a thick chain on our oven,” said Sérgio Pinto, Luiz’s nephew and resident of Quilombo Sacopã. “That gate there? He padlocked it, no cars could come in or come out. We had to jump the wall. Taxi drivers wanted to eat here, that’s how we made money. After awhile, César Maia came to apologize as a candidate to some government post.”

As the women cooked the pork and beans dish in the kitchen, Sérgio spoke of how happy he was with the quilombo’s victory.

“I work as a night guard and I kept checking my watch all the time because I was so anxious about today,” he said. “I think I am the happiest one here, but the victory is really my uncle’s. I got tired of seeing him arrested, held by his wrists like a thief. As if we were criminals.”

“They tried to remove us several times–there were residents [of the luxury buildings around the quilombo] who came here and threw money on the table. There was one who gave a blank check to my uncle and said ‘fill it out’ and called my uncle stupid [when he declined].”

Sérgio also revealed that he is planning to engage the younger generation of his family to make sure they will protect his uncle’s legacy.

“I am the older nephew so I saw the struggle in my lifetime,” he said. “I am meeting with the younger ones because I want them to preserve this place like we did. They saw the struggle, but they didn’t feel in their skin what it’s like to be evicted. So they have to honor my uncle’s legacy.”

Rural vs Urban

Representatives of Quilombo Cruzeirinho Juanice Ribeiro Ferreira dos Santos and Mariley Barbosa de Souza traveled six hours overnight to receive a document that will help them get the title to their home. Their rural quilombo is home to around 200 people who settled around a church in the northeast of Rio de Janeiro State after slavery was abolished.

Unlike the struggles of Sacopã, Juanice says Cruzeirinho’s six-year journey to recognition has been quick in comparison to most quilombos. This may be attributed to the fact Sacopã is not only an urban quilombo, but one located in a wealthy neighborhood that has continuously tried to interfere in the recognition process. According to Juanice, Cruzeirinho is not in anyone’s path and nobody has tried to evict them.

Even so, they seek quilombo recognition because they believe it will improve their community.

“To us, this is another victory, you know? It’s a document that we will use to start a process and to get more resources [from the government] to better our community,” said Juanice.

Mariley added: “We think if we are officially recognized we will get more help with basic services and money for school lunches.”

A bittersweet celebration

Although the event was a happy one, there was space for calls of further resistance for other quilombos fighting for titles. Luiz, who says he’s spent 50 years fighting for this victory, was happy but disappointed in how long the whole process took.

“I am very happy, yes. But this is something that could have been done a lot faster since it’s a constitutional right. I mean, I am happy because it happened, but I am still in denial because of the fact that it took all this time.”

According to Incra there are currently nine quilombola communities in the process of titling in Rio.