For the original in Portuguese by Ruben Berta, published in O Globo, click here.

Surrounded by rubble, approximately 170 families are still living in the community neighboring the Olympic Park in Barra da Tijuca.

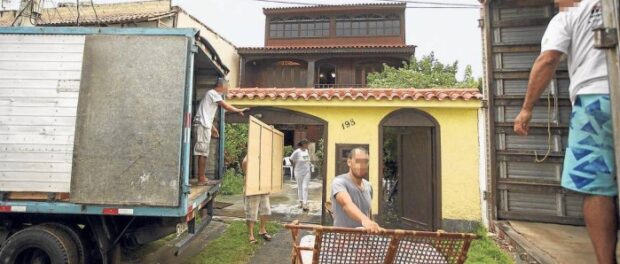

RIO–The story of the Vila Autódromo community, which neighbors the future Olympic Park, starts in the 1960s with a few haphazard occupations cropping up along the edges of the deserted Jacarepaguá Lagoon, and is currently in the middle of a chapter that could well be called “The Contrarians.” Despite demonstrating his dissatisfaction in doing so, over recent months Mayor Eduardo Paes has conceded to give millions in compensation to those who have vacated property on the edge of the water or in the way of the construction of new roads. The highest values—up to R$3 million (US$1 million) each—however, have not left those who had to leave happy, as those recipients are middle class people who owned commercial properties or homes that would not be out of place in any condominium in Barra. The story ends with approximately 170 families—for the most part families in need—that still remain in the favela, surrounded by the rubble of all that has been demolished. It is highly likely that the community will still be there at the time of the 2016 Olympic Games.

Court Battle Since 1993

While engaged in an endless court battle—which started in 1993 and to this day remains unresolved—the City decided to open the public coffers in order to expropriate property in the region. Just from November last year until now, according to a survey conducted by the office of City Council member Teresa Bergher (PSDB) at the request of GLOBO, no less than R$95 million (US$30 million) were released to compensate 116 people. Within this group, 33, or less than one third, received amounts over R$1 million (US$300,000). Their combined total was R$55 million (US$17 million), or nearly two thirds of the overall amount.

“I find [paying high compensations] absurd and an unacceptable business. Yet, the fact remains that at some point someone came and legalized the situation of these people. At a certain moment in time, a band of NGOs, international organizations, political parties and public defenders defended these guys… And this is the result: people who do not need it are receiving a fortune to vacate a public area. Demagoguery rules, hypocrisy comes, and this is what happens. And we were only able to empty the area after lots of negotiation. There’ve been six years of negotiating this,” said Mayor Eduardo Paes.

Among the 33 who received more than R$1 million, there are several curious cases. The largest amount for a property went to business owner and race car driver Cláudio Capparelli: R$2,992,341 (US$947,334). The compensation was paid to reimburse him for the competition car workshop he set up more than 20 years ago close to Jacarepaguá Lagoon. Showing a great deal of dissatisfaction, Capparelli says he had bought possession of the land and did not want to leave, but was forced out by the City.

“Nobody wanted to leave there. We were forced to do so by a type of guerrilla tactic by the City who started to make access difficult and set up a series of obstacles. Life became very difficult, we were suffocating. So, I decided to give in when we arrived at a value that I felt was reasonable. I did not take into account that my property was a business and how much the move would disrupt that. I only took into account the size of the building and how much it was going to cost to set up a new workshop in Barra. This is not going to come out at less than R$3 million (US$1 million),” the businessman complained. He added: “As a taxpayer, I really believe there could have been a better way out than these compensations. It would be much cheaper, for example, to re-urbanize the area.”

On the list of those who received the largest sums, there is also ex-pilot Lucas Molo, who was compensated with R$2.3 million (US$728,148), also for a workshop which, according to the City, was built on a protected area of the lagoon. He protested solely by means of an official statement, stating he was against the dispossession, yet ended up agreeing to leave primarily as he does not see a future in motor racing in Rio. Currently, Molo lives in California in the United States, where he owns an MMA gym.

Two officers from the Military Police also appeared on the list of the most highly compensated: José Cleidson Ramos Reis, from BOPE, with R$1.299 million (US$411,245) and colonel of the reserve José de Oliveira Penteado (R$2.2 million or US$696,490). Penteado is notorious for having been the BOPE commander during the hijacking of bus 174 that ended with the hijacker and one hostage dead. Cleidson was sought for comment through the Military Police’s press office, which said it could not respond to a request about a particular officer. Penteado was not available for comment concerning the compensation.

Even an environmentalist from São Paulo was compensated: Mauro Frederico Wilken, president of the Ecological Society of Santa Branca (an inland city in the state of São Paulo) and alternate member of the National Council of the Environment (Conama), was compensated for R$1.199 million for a property along the protected area of the lagoon. He was unavailable for comment.

Advisor of the Rio de Janeiro Bar Association (OAB-RJ) and a lawyer specializing in property law, Antônio Ricardo Corrêa, confirmed that in situations of consolidated irregular occupations, the public authority has no other option but to compensate or award another dwelling.

“The law does not give right to property when a public area has been occupied,” he said. “But, if there was a period during which the government allowed people to build and make improvements to their homes, then those people must be compensated in order to remove them.”

Of the 760 properties listed by the City in Vila Autódromo, 590 have already been vacated. Of these, 336 were families in need that went to the public housing complex Parque Carioca. The rest were financially compensated. Despite the evictions, in aerial photos it is still possible to see that the favela, which is next to the site of a future hotel for the media and International Broadcasting Convention (IBC) of the Olympic Park, still remains. There is a lot of rubble spread out. One of the clearest pieces of land has come to be used as an improvised parking lot for Olympic construction workers.

Wearing a black t-shirt with the words “SOS Vila Autódromo,” Luiz Cláudio Silvo, a physical education teacher, is among those who are resisting the move. A lover of sport, he said the Olympics is fast becoming the biggest nightmare of his life.

“What you see here today is a war scene. Why not take care of the community and leave a social legacy?” he asked, remembering that in 2013 the residents themselves developed a prize-winning re-urbanization project proposal, with experts from federal universities UFF and UFRJ projecting that it would cost little more than R$13 million (US$4,115,622) to implement.

Mayor Paes Admits Maintaining the Community

Doorman Francisco Marinho says he struggled 13 years to acquire every brick for his house and has no intention of leaving. He has been refusing to let City workers measure his house for a future calculation for compensation.

He said: “When we work for the wealthy people of Barra, we smell. Nobody wants a favela next to the Olympics. But I have made my life here. I have fought to build every wall. I did not go to one of the apartments they were offering because I know that someone from the favela does not know how to live in an apartment with the taxes and all the costs involved.”

Despite all the dispossessions, Mayor Eduardo Paes admits that among the 170 that still remain, those that are not in the way of the new roads or alongside the lagoon can stay. However, when asked, the City was unable to say how many people this applied to. Paes also admitted to upgrading the area by bringing in missing services.

Public defender João Helvécio de Carvalho, who is accompanying the case of the residents in need, says he hopes Paes will allow those who wish to stay.

“We hope there will be dialogue and that this intention is fulfilled. And that those who stay, stay in a dignified manner.”