For the original article in Portuguese by Tiago Dantas and Márcio Menasce published in O Globo click here.

Five years after the first Minha Casa Minha Vida (MCMV, or My House My Life) public housing apartments were delivered, residents still encounter violence, structural problems, fraud, and a lack of publicly-funded infrastructure and recreation spaces. In some complexes problems stem from high default rates; in others drug trafficking undermines a sense of security. In some of the first MCMV projects in Brazil—Feira de Santana (Bahia), Campinas (São Paulo), and Rio de Janeiro—successfully obtaining one’s own home is still a headache for residents.

Minha Casa Minha Vida is one of President Dilma Rousseff’s hallmark programs amid a second term marred by a growing political crisis, budget cuts, and proposed tax hikes. Without any other important projects ready to be delivered, the government has focused on the housing program. Since August 31, 17 complexes have been launched, with the president and seven other ministers in attendance. According to the federal government, up to 360,000 families will receive units by year’s end.

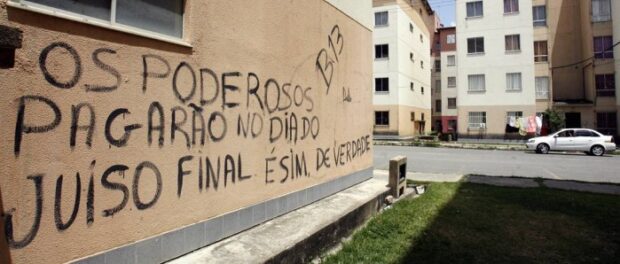

The first MCMV complex was launched on March 31, 2010 in Feira de Santana, Bahia. Designated for 440 low income families, the Residencial Nova Conceição is known locally by the name of a local criminal faction. Although the organization’s influence has since receded in the neighborhood, police report the gang’s spray-painted initials are still visible on nearly all of the complex’s 22 buildings, along with graffiti images of revolvers and the number 157—the penal code for theft. Seven people have been murdered in the condominium.

Inside the apartments iron barricades and bolt-locks protect every door. Residents cite, however, that these precautions have not deterred the theft of electronic appliances or squatting in unoccupied apartments. Lack of policing is one of the most frequent complaints among those living in Nova Conceição.

“Security here is terrible. I don’t let my children go out alone. In June, we went outside and an armed man turned up to shoot someone. I’d prefer to go back to renting,” said L.N., 51-years-old, who asked to remain anonymous.

In the last five years, two people have tried to sell security services to residents—a strategy employed by militias. Those who didn’t pay suffered retaliation, losing access to postal services, for example. A majority of the residents receive the Bolsa Família government cash transfer. Aside from the absence of police, residents bemoan the lack of doctors and day care centers in the area. In addition, the playground in the complex was destroyed, and the lights on the soccer field haven’t worked for at least two years.

Minha Casa Minha Vida isn’t solely the federal government’s responsibility. The state government must provide security. According to Lieutenant Colonel Vanderval Ramos from Feira de Santana, a police station can’t operate in the Nova Conceição housing complex, but “it can be constantly patrolled.” Health and education facilities are the responsibility of municipal authorities. Feira de Santana’s Housing Secretary, Sandro Ricardo, says that the city researches the public services necessary for each housing project. According to the Ministry of Cities, 6% of funds for each project are earmarked for “contracts to build health and education facilities, just as there are funds designated for social welfare, security, and other needs complementary to housing.”

Water and Electric Bills Unpaid

Fraud is another problem in Nova Conceição. In 2011, fifty units were sold, and last week, O Globo interviewed two individuals who paid R$200 (US$52) for rent. According to the Ministry of Cities, the private sale and leasing of units is prohibited before the property has been purchased in full from the government, a process that takes ten years. Violators of this rule are obliged to “repay the subsidies received and are barred from any other social programs funded by the federal government.”

In Rio, the Jardim das Acácias complex near Complexo do Alemão was the city’s first Minha Casa Minha Vida project—inaugurated on June 24, 2010 with 291 units. Five years later, residents have stopped paying for water and electricity services as well as the condominium fee. Properties are not designated for commercial use, yet one had been converted into a beauty salon. Hairdresser Jéssica Cunha, who has lived in the apartment since her family was removed from Morro do Adeus, said she decided to start her salon from home due to the high cost of renting commercial space.

“We never used that room anyway. It was an empty space,” she said.

The building manager of Jardim das Acácias, Pedro Pascoal, said payments to CEDAE—Rio State’s water and sewerage utility—are short nearly R$100,000 (US$26,000). According to Mr. Pascoal, of the 291 units, only 120 pay the monthly R$92 (US$24) condominium fee on time. This money doesn’t cover payroll expenses for the facility’s employees and an accountant or the upkeep of the property’s security cameras and electronic gate.

“We have to pay for everything here. In the favelas, we didn’t pay for electricity, water, or a condominium fee, and many people don’t realize they need to pay for these things,” Pascoal said.

In another housing complex in Rio, Jardim das Palmeiras, a bar opened up in one of the apartments. The bar’s owner doesn’t live on the property anymore, despite having received the unit from the government.

Families that have a gross monthly income of less than R$1,600 (US$424) pay for their housing over the course of ten years at a rate of 5% of their income. If they can’t cover this expense, they can lose their home. “The goal of Minha Casa Minha Vida is not to repossess homes that have defaulted, but to help recipients overcome potential obstacles,” the Ministry of Cities said in a statement.

In São Paulo’s first complex, Campina Verde, residents face a different problem. They pay for security, but cite isolation as a major issue. There are no children in the streets and residents only use their units for sleep.

Traffickers and Militias Invade Condominiums

In many Minha Casa Minha Vida condominiums drug traffickers take control of the units and drive out residents. This was the case in Haroldo de Andrade in Barros Filho in Rio’s North Zone. In September, a Civil Police operation was met with gunfire from traffickers. One suspect died and three others were arrested. Police carried out search and arrest warrants in 60 apartments where traffickers from the nearby Morro de Pedreira favela were operating. According to the Civil Police, trafficker Carlos José da Silva Fernandes, also known as Arafat, had evicted 80 families who had settled in the MCMV complex from areas controlled by a rival criminal faction. In the West Zone, militias have taken over MCMV condominiums. In August, a Civil Police operation in seven neighborhoods saw the arrest of four men and seizure of criminal accounting records. Warrants were carried out in 39 MCMV condominiums. In total, Rio’s police calculate that as many as 30,000 residents in 10,000 apartments are exploited by militias.