For the original article by Saulo Pereira Guitarães in Portuguese published in Vozerio click here.

Whether it is the flat City of God or the steep Santa Marta, senior citizens living in favelas have to overcome various obstacles in their daily lives. The good news is that they manage to, but the increase in life expectancy requires that there be urgent improvements to this situation.

Everaldo Leite swapped his scissors for a cane. With his cane, the 80-year-old former barber goes up and down the hill in Santa Marta where he lives. Seven steps separate his front door from his living room on the first floor. On the second floor, 11 steps up, there are two bedrooms. Eight more steps lead up to the third floor attic and “penthouse” overlooking the lagoon. “I used to come up here more, but I stopped because of the climb,” says Everaldo. For him, accessibility is a problem that starts on the street and continues at home.

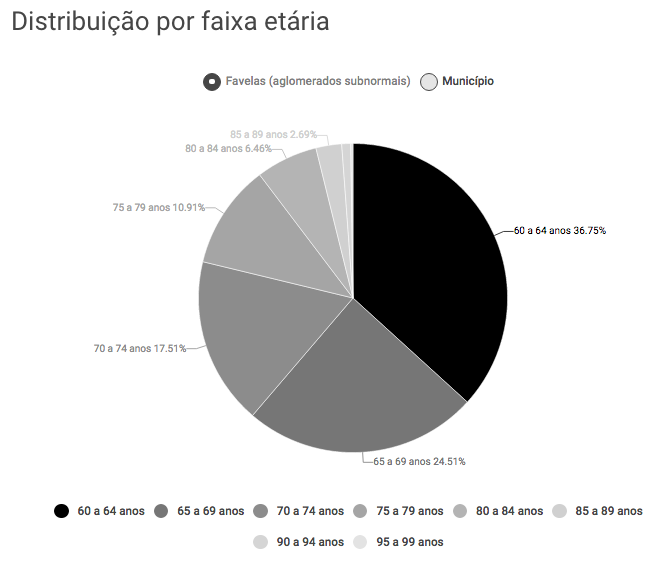

The former barber is part of a group of about 100,000 people aged 60 or over who live in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas, according to the latest census in 2010 by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE). Those in this age group are in the category provided for by the Statute for the Elderly which recognizes their right to leisure and health care assistance among other policies. Services that, because of where they live, are almost inaccessible.

“The worst problem here on the hill are the stairs,” notes Everaldo. He’s had difficulty walking for the last 15 years. He also lacks strength in his left hand and in one arm. But these problems don’t hold him back. He still goes to Botafogo to pick up his medication, schedules appointments at the dentist and does the household shopping. He shares his home with his ex-wife and Tom, his cat and “best friend.”

Luz Maria Silva, however, feels less confident. “I’m afraid to go to more distant places, the bad sidewalks hinder me,” says the resident, known as Dona Xuxa, of City of God. She is 67 years old and she earned this nickname while working at the department of motor vehicles due to her striking resemblance with Brazilian celebrity Xuxa. Ten years ago, a stroke caused her to rely on a walker to get around. Poorly maintained sidewalks, garbage, narrow alleys and cars on the street are some of the obstacles in her way. “There is a lack of space for people to walk,” complains Nancy Silva, 82, Xuxa’s neighbor in City of God.

“Living alone in a favela is a challenge for any older person,” said Tarso Mosci, president of the Rio chapter of the Brazilian Gerontology and Geriatrics Society. Day after day, winning this battle requires a number of adjustments. Since it is difficult to carry many bags up the hill at one time, Everaldo goes to the market up to four times a week. Luckily a sympathetic neighbor almost always shares the burden. “Only when you come to depend on others do you notice there are people who help the elderly,” he says.

“After security, accessibility is the main obstacle for older people in the community,” says social worker Maria de Lourdes Braz. Since 1991 she has coordinated the Casa da Santa Ana, a community day center for seniors in City of God. Dona Xuxa gets physical therapy on site and Nancy is honorary president after retiring as the first employee hired. The center serves about 150 people every month and is supported by the United Nations and a partnership with Yale University.

Rights

In addition to accessibility, older people living in favelas have difficulties to exercise other rights. One example is access to health care. “Most communities do not even have a health facility,” said Rossino Diniz, president of the Federation of Favela Associations of the State of Rio de Janeiro (Faferj). If someone gets ill, they depend on public transportation to get to medical care.

But access to transport is also a challenge, not only because the buses are hardly accessible. “It is common that alternative transport drivers do not respect the elderly and they charge them for what should be a free service,” says Nelson Felix, who has a Masters degree in Social Work and is a member of the Regional Social Service Council of Rio. The rule is set out in Article 401 of Rio Municipal Law. “Those who needs transportation to go to the hospital don’t have time to call the police,” added Felix.

Article 38 in the Statute for the Elderly also states that people in this age group have priority access to 3% of the units of any housing project funded by the government. “But the rule is rarely enforced,” says Felix. Despite difficulties, the elderly who live in favelas maintain a surprising vitality.

Aloísio Dos Santos, 70, and Marieta da Silva, 86, are examples of this. The two frequent events at the Casa de Santa Ana and have maintained a “conversation” for four years, the term they use to describe their serious relationship. The couple faces resistance from family members, but do not let it bother them. They like each other and want to be together. “While you have emotion, you’re alive,” says Aloísio.

The Future

What would improve living in favelas for older people? Seu Everaldo has the answer on the tip of his tongue: “I would put an escalator on the hill. I know that would involve work. But gradually installing one would be possible,” he says. “Initiatives such as the cable car in Alemão, which does not work when there is bad weather, serves tourists more than residents,” said Felix. The truth is that solutions need to be thought up.

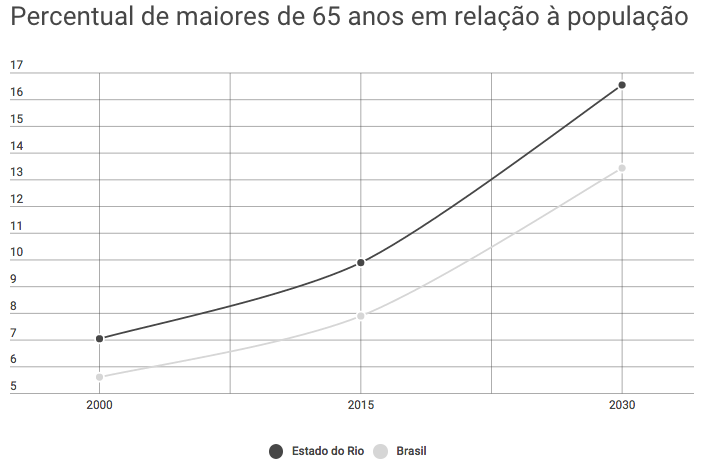

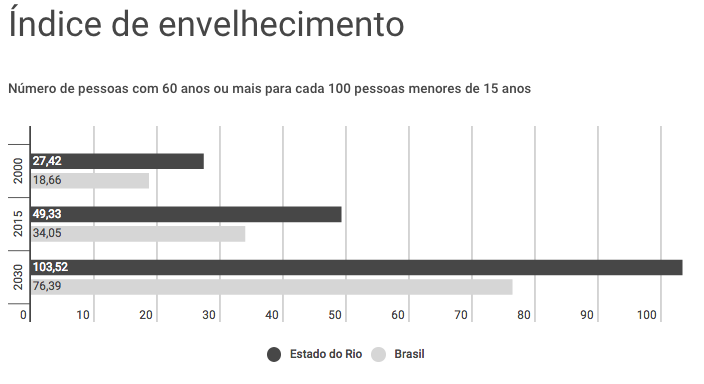

“We are going to have an increasingly aging population in areas with a high concentration of low-income people,” says Luiz Cesar Ribeiro, coordinator at the Metropolises Observatory and professor at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). According to him, the main factors for this are the reduction in the number of births and the increase in life expectancy.

According to the IBGE, the state of Rio in 2030 will have more senior citizens than people aged under 15. The eldery who today represent less than 10% of the population will increase to more than 15% by then. And life expectancy which is now 75.8 years will increase to 79.4.

“The question is how do we bring these people the things they need,” explains Ribeiro. In the opinion of experts like Dr. Alexandre Kalache, director of the International Longevity Center (ILC-Brazil) and former head of the World Health Organization (WHO) Aging and Health Program, the provision of living spaces, health facilities and other services will have to increase in number and improve in quality.

Meanwhile, seniors like Dona Xuxa, even with difficulties, are enjoying the privilege of having a long life. “I go for walks, go to my friends’ houses and do not give up having my beer on the corner. If you only stay at home, you wither away.”

Older People in Rio

Charts made using data from the 2010 census.