On his way past a group of houses at the top of the hill of Babilônia favela in Rio de Janeiro’s South Zone on March 31, Neighborhood Association president André Constantine stopped to tell two residents leaning out their windows about an important community meeting that would take place the following day. “We need to organize to take action together,” he stressed. “We need strength now.”

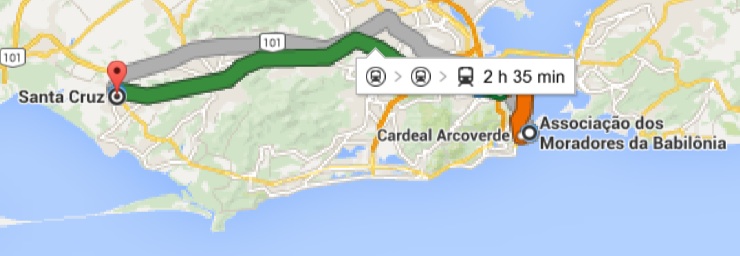

In a previous meeting at the Municipal Housing Secretariat (SMH), André had been informed that these residents and their neighbors had a choice: they could accept relocation to Chapadão, about 35 kilometers miles away in the North Zone, or accept relocation to Santa Cruz, some 65 kilometers away in the West Zone. This was the case for any Babilônia resident in the area marked as high risk (of landslides due to heavy rains on steep slopes), residents of the area marked as an Area of Environmental Protection (known by its Portuguese acronym as APA), and those currently receiving social rent from the government, some of whom have already been removed from homes in the high risk or APA areas.

More than just another case of forced evictions in pre-Olympic Rio, the situation of these residents exemplifies the broken promises of the favela upgrading program Morar Carioca. Six years ago, the City promised they would be relocated within the side-by-side favelas of Babilônia and Chapéu-Mangueira in new apartments built through Morar Carioca investments. Now in 2016, one of the three promised apartment blocks has still not been built and funding for the project has run dry. As of a community meeting on April 3, the “choice” between Santa Cruz and Chapadão had already disappeared—André informed social rent recipients that the City plans to relocate them all to Santa Cruz.

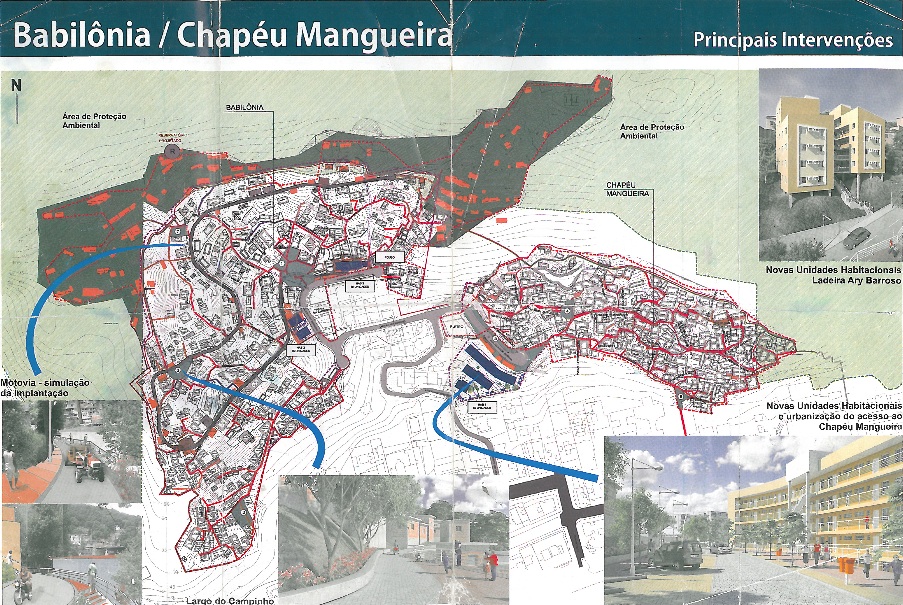

Morar Carioca was a program launched in 2010 with the goal of upgrading all of Rio’s favelas by 2020. Heavily marketed as a key component of the Rio 2016 Olympics’ social legacy, the program received local and international praise, winning the 2013 City Climate Leadership Award for “Sustainable Communities” from the C40 network of cities. (Note that Mayor Eduardo Paes has been the chairperson of C40 since 2013.) C40’s materials state that “the aim [of Morar Carioca] is to keep people within their own communities” and “the goal is to resettle all those living under risky conditions by 2016,” and they highlight the case of Babilônia and Chapéu-Mangueira as an implied success of the green sustainability initiative. Across the city, however, planned projects never materialized and, according to sociologist Orlando Santos Jr, Morar Carioca “ceased to be a priority to the municipal government, with no official explanation.”

Misplaced priorities

One of André’s biggest criticisms of Morar Carioca is the prioritization of projects. He has copies of a map produced by the City in 2010 in which different areas were ranked from no-risk and low-risk to high-risk of landslides, marking residents of high-risk areas for relocation within the community. A few residents were removed; many others remain.

“From 2010 to now,” he says, “six years passed and nothing was done. No improvement was made to minimize the risks due to heavy rains… For me, this already constitutes a crime.”

In the context of this identified urgent need, investment in solar panels and green architecture had value but also signalled a disregard for community priorities. He compares the situation to a doctor who, after diagnosing a patient, doesn’t treat the most serious illness or injury, potentially leaving the patient to die. “From the moment the City identified an area…with the classification of high risk, the City must bring about the construction” to address the issue. The Neighborhood Association president has pushed for the City to deliver the remaining promised housing through both written letters and in-person meetings, so far to little avail.

According to André, when two of the promised three apartment blocks were built under Morar Carioca, two tailored apartments were designated for individuals with disabilities but the rest were assigned through a lottery. He argues there should have been a list of families in order of priority for housing, posted on a wall for everyone to see, beginning with people living in the area of highest risk and the elderly. Instead he recalls, “We didn’t have this transparency here. We didn’t have any dialogue with this disrespectful City.”

This experience is a far cry from the design of the Morar Carioca policy, which was lauded for its emphasis on community participation in directing project implementation. An architect contracted for Morar Carioca in Babilônia told The Guardian that the City and State governments had not allowed the level of community participation the architects would have liked. André claims that at no point did the City present a full project plan, with a timeline and budget, to the community; nor have City officials officially informed the community what everyone already appears to know—that further works have been indefinitely suspended.

Marcia Sales is one resident whose family was removed from their home, located in both the area of risk and the APA. She echoes André’s frustration with the Morar Carioca process: “This work, in my opinion, was not done in partnership with the community… They already came with [the plan] ready. You basically don’t have an option, either you accept it or you don’t.”

When they vacated their house in 2010, Marcia’s family was awarded social rent while they waited for a promised Morar Carioca apartment, and they “were lucky,” in her words, to find a place lower down on the hill to rent. Despite the fact that officials had said in 2010 that their home could fall and destroy a house directly below it, the City did not actually demolish the home until earlier this year. Now, Marcia says the City is threatening to take away the social rent: “If you don’t accept to go to these places,” referring to Santa Cruz, “[the City] says, ‘in that case [the social rent] will be cut.””

Having just started a new job at a neighborhood day care center, Marcia doesn’t know how her family would manage to access or find new employment if they lived in Santa Cruz, especially given the current economic crisis. Plus, she adds, she likes living so “close to everything” in Babilônia, where she has lived her whole life along with her friends.

Mobilizing in response

At recent open community meetings, André and other residents have been planning for the process ahead. “It’s not your fault,” the Association president assures attendees, that the City has failed to fulfill its commitments, adding that “sometimes what the City presents is not real.” He argues a strong collective community response is the only way to hold the City accountable to deliver promised homes within the neighborhood. The City is trying to negotiate with families on an individual basis, a strategy that has been documented in eviction cases throughout Rio. André describes this as “a form of weakening our cohesiveness,” and asks residents only to agree to meet with the City with the support of the Neighborhood Association and the public defenders.

“What we need now,” he insists passionately, “is judicial action and protest… We need to create political pressure.” This includes seizing opportunities for international media coverage ahead of the Olympics, and the community plans to use signs in both Portuguese and English in upcoming protests.

Infrastructure quality

Under Morar Carioca, two apartment blocks were constructed, the main road was paved—with asphalt and recycled rubber tires—and extended, and drainage systems were extended and fortified.

But go to the first apartment block, which opened four years ago, and resident João Medeiros da Silva can point out multiple locations where walls and ceilings feature damp patches, leaks and corrosion, and where a light knock on the external walls will result in a surprisingly hollow sound.

Go to the second block, which opened just last year, and Antonia Bertania can point out where water enters through her daughter’s bedroom wall during heavy rains. Her family moved into the brand new building on April 9, 2015; the first incident of water leaking through the walls occurred one week later.

Next to the first apartment block, an empty square lies barren where three families’ homes were removed to clear space for a cultural and social center that was never built. At the site destined for the undelivered third apartment block, a number of small businesses were removed along with a plot of old trees.

The paved road facilitates access to a large part of the community and is especially important for emergency services. Yet it only goes part of the way to its original planned destination. When asked when he thought the road would be completed, André chuckled, shrugged, and guessed, “never?”

And then there are oddities like the occasional electricity posts towards the end of the road that are stuck, defiantly, in the path of any vehicles wider than a motorbike. The road and the drains running alongside it have sections that are in need of maintenance, but André says there’s no evidence of a plan or budget in place for upkeep of the infrastructure.

Reacting to the award

In response to the C40 award and recognition Morar Carioca has received over the years, André states: “This project is an embarrassment. And to win these prizes, it’s even more embarrassing.”

He acknowledges that Morar Carioca in Babilônia has been labeled as the “green Morar Carioca,” but points out that the Area of Environmental Protection, established in the 1990s, could have been more logically drawn from the point of the highest house upwards, rather than including part of the land that had already been settled. In his view, “it’s obvious that these things give a lot of visibility, the environmental question… Since that recent event, the Rio+20 [United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development in 2012], it’s just ‘for the English to see.’ The problem is that everything is done ‘for the English to see,’ and things don’t work in reality.”

He argues the Morar Carioca project is just one part of a larger project of “the mayor who has removed more [people] than any other in Rio’s history” to create “a city that’s very good for investing, a business city, but really bad for the citizen… A city where the poor, black, Northeastern people who built it are not included.”

Marcia, in turn, admits that Morar Carioca is “beautiful on paper,” but it “really needs to function in another form, one which attends more to the needs of the community.” She concludes that it would be good if the people who gave the award “could come [here], because what Morar Carioca is, how Morar Carioca functions, is truly different from what is presented.”