For the original article by André Cabette Fábio in Portuguese published in Nexo click here.

Researchers analyze the reasons why Rio de Janeiro Military Police have a higher rate of suicide than the state population.

Besides the risk of dying in combat, police also have a greater chance of committing suicide. Long working hours, being away from home and family, lack of professional recognition and an absence of psychological support are all contributing factors.

Launched in late March, the book Why Do Police Kill Themselves?, by the Rio de Janeiro State University’s (UERJ) Suicide and Prevention Study and Research Group (Gepesp) in partnership with the Rio Military Police, notes that in 2009 Rio de Janeiro Military Police officers were 6.6 times more likely to commit suicide than the state population on average. The problem is repeated in other police forces in the country, but it is taboo to speak about. And the lack of reported cases suggests that it is even more serious, the study finds.

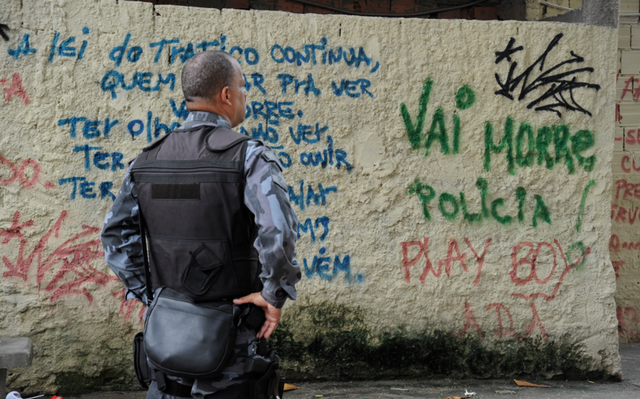

“Living under the banner of violence, to believe in it as a way to resolve conflicts, changes our relationship with death and consequently subtracts gravity from the meaning of life,” says Ibis Silva Pereira, Military Police reservist colonel and former chief of staff to the Rio Military Police General Command who has a Masters degree in Philosophy.

Conducted through a partnership between five psychologists from the Military Police and UERJ researchers from different areas, the study states that 10% of 224 Military Police officers interviewed for the study attempted suicide, and 22% thought about doing so. “Despite the severity of the problem, suicide among police has not received due attention from the government or international and national law enforcement organizations,” the book says.

Fifty-eight Military Police officers committed suicide in Rio de Janeiro state between 1995 and 2009, according to Military Police data. Fifty-five of these suicides occurred on days off. According to Gepesp and Military Police, it is likely that there’s an underreporting of cases.

From the investigation of 26 suicide cases, research traced the profile of the victims. They are generally sergeants, corporals and soldiers; married; between 31 and 40 years old; and work in operational units. See below some of the conclusions about why suicide is such a common problem among the police and what can be done about the issue.

Why police officers commit suicide

The taboo around suicide

One of the main difficulties in dealing with the problem of police suicide is the taboo around the issue. Military Police with emotional or psychiatric problems suffer prejudice, and suicide is treated as an embarrassment within and outside the police. “The family itself is ashamed, regardless of whether they are police or not,” said Dayse Miranda, coordinator of the book Why Do Police Kill Themselves?.

Admitting to suicide also involves an economic issue. When a police officer dies in combat, his family receives a pension equivalent to full retirement. Families of police suicide victims receive a pension relative to the time during which the police officer worked. They also do not receive life insurance. Research found reports of colleagues who had altered crime scenes where police officers were found dead due to suicide as a way to cover up what had happened. Others exposed themselves excessively in combat, as a way to die covering up their own suicides.

“Four police officers recounted that they entered confrontations in the Maré favela without using a bulletproof vest on days they ‘wanted to die.’ They knew that if they didn’t die like that the family would lose the benefits,” said Dayse Miranda.

Work schedules and overtime

Police work schedules harm their rest, affect their psychological health and distance them from their families and other support networks that could help them in times of crisis. There are several shift models. One of the most detested is working for 12 hours with 24 hours off, followed by a further 12 hours of work and 48 hours rest.

The problem, according to Dayse Miranda, is that Military Police officers in Rio de Janeiro have had to work that second day off because of the so-called Additional Service Regime (RAS). This is a sort of optional overtime, but because there aren’t enough police it is becoming mandatory in practice, it is claimed.

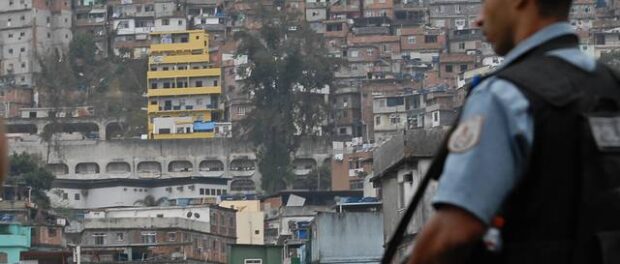

This is compounded by the fact that many police officers live far from the area where they work. “There are police officers who take three hours to get to the Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) base where they will spend the whole night awake with a gun,” she says.

The pressure on the police force worsens during major events or political events which increase working hours. “At the time of the demonstrations [in June 2013], the shifts were 24 hours long and police left work the following day,” says Dayse. Even people in administrative areas–often made to take desk jobs because they have health problems–go through this. “If a police officer has to work three days straight, he will,” she says. She also points out that this effort is not recognized by society.

“In Rio de Janeiro, police officers are seen as killers. Brazilian society does not know about police suffering. They know about the police officer who kills, but not the police officers who kill themselves,” says Dayse Miranda.

Like the Rio police, the São Paulo Military Police has also created a way for police to work overtime. Drawn up in 2009 under the administration of Mayor Gilberto Kassab of the Social Democratic Party (PSD), the Delegate Operation is a partnership between the City government and the Military Police through which police officers can work for the municipal administration on their days off to earn extra income, if they wish.

Rigid hierarchy

According to Dayse Miranda, Military Police officers do not regard hierarchy as a problem, but resent the abuse of authority. Among the reports that were gathered there is one about a policeman who was hit by his superior. The researcher also reports the case of a police officer who told his commander he was not well, he lived far away from work and had family problems. “The boss ordered he be arrested. He went to the bathroom and killed himself in the unit,” she says.

“The police command doesn’t understand that you have to treat officers well because they deal with difficult, tense people, and have to deal with a difficult environment. You can’t make Military Police officers’ lives hell,” says the retired colonel José Vicente da Silva Filho. He cites the US military as a positive example, which has focused on treating officers in a more humane way.

Dayse points out that abuse is not an exclusive problem to the Rio Military Police, but is something widespread among police forces.

Lack of a support system

Military Police officer Miguel took mood disorder medication that was prescribed by a doctor friend, but did not receive any psychological or psychiatric treatment. He was playing Russian roulette at home in front of his wife and children and mentioned he had “the desire to shoot himself in the head” at work, but received no specific care. His suicide is one of the cases reported in the book Why Do Police Kill Themselves? His name has been changed.

This is not an isolated case. Practically all Brazilian police officers suffer from lack of psychological care, particularly from specialists in suicide. The Rio de Janeiro Military Police is considered well served with the number of psychologists it has compared to other police departments in the country, but still it is not very effective. There are 95 psychologists to treat 40,000 Military Police on active duty and in reserve. And only two psychiatrists, one for the police and another specializing in children, to attend to the officers’ children.

Access to firearms

Data from 2000 from the Mortality Information System show that 51.5% of suicides in Brazil are committed by hanging. Firearms are second, at 19.6% of the total.

Among the police, however, the ratio is different. Of the 22 cases that were researched for the book, 14 deaths were caused by firearms.

What can be done to improve the situation for police officers?

Demystify suicide and implement support programs

Dayse Miranda advocates the creation of programs designed exclusively for officers who show signs of contemplating suicide. She cites the São Paulo Military Police as a positive example having created the Suicide Manifestations Prevention Program in 2004.

Remove guns from police with psychological problems

The book recommends that police officers at risk of suicide have their weapons temporarily seized–including the amendment of the Military Police internal regulation.

More humane treatment in the police hierarchy

According to Dayse Miranda, those in command of the police must treat their subordinates more humanely. “We have a story of a sergeant who attempted suicide six times and was removed from his job. At the end of 2013 his commander made the difference, gave him back his position of command. This restored his self-esteem and allowed him regain the respect of his colleagues,” says Dayse Miranda.

Reduce working hours

According to the researcher, it is also necessary to increase the number of police officers to ensure that inhumane shifts are not employed, especially for major events such as the Olympics in Rio de Janeiro.

In addition to allowing for rest and helping to reduce stress, shorter shifts allow police more time to become closer to family and friends, strengthening their support network.