The New Urban Agenda is responsible for establishing the policy frameworks that will guide the governance of the world’s cities for the coming 20 years.

From October 17-20, 2016, the United Nations, led by UN-Habitat, will host the Habitat III Conference in Quito, Ecuador. This conference, held every 20 years, will bring together representatives from nations around the world to decide on the “New Urban Agenda” establishing the policy frameworks that will guide the governance of the world’s cities for the coming 20 years. The previous Habitat conference was held in 1996 in Istanbul, Turkey and had two main themes: “Adequate shelter for all” and “Sustainable human settlements development in an urbanizing world.”

Leading up to the conference, there were numerous preparatory meetings, national reviews and virtual meetings where experts around the world gave their input, later put together in the “Zero Draft” of the New Urban Agenda, released in May 2016, revised since and now released as the final draft of the New Urban Agenda.

In the context of major changes to technology and globalization within the last 20 years, the New Urban Agenda generates an opportunity to reimagine the world’s urban future. As academic David Satterthwaite notes, “given the very poor housing and living conditions and lack of basic services suffered by so much of the urban population in low- and middle-income countries, there is a very serious need for new approaches.” However, he also notes that there is a distinct vagueness to the New Urban Agenda. “No one is actually sure what it is,” he says.

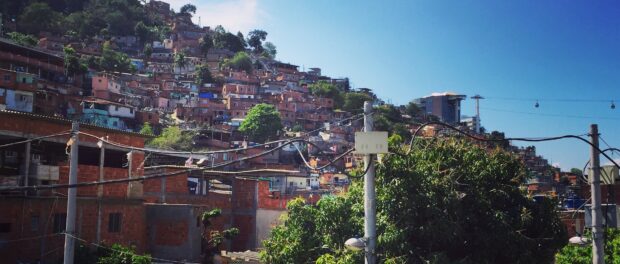

These questions are incredibly important for a city like Rio de Janeiro, where urban transformations around the hosting of the World Cup and Olympics have dramatically altered the city’s landscape. A city that once denounced the favelas as “aberrations,” but then largely decided on a policy of acceptance and attempted urban upgrades, has in recent years returned to using removal as a commonplace policy option. The administration of Eduardo Paes has removed more residents in favelas than any other mayor. So what exactly does the New Urban Agenda say about the future of informal settlements, and what, in particular, does Rio de Janeiro have to learn and contribute to this discussion? Below is a summary of the main themes of the New Urban Agenda.

Governments need to be more responsive, committed, and accountable to citizens

The New Urban Agenda recognizes that the limiting factor to successful urban development is often a lack of government accountability. As early as clause 14 in the draft, the document states that “to achieve our vision, we resolve to adopt a New Urban Agenda guided by the following interlinked principles: … Leave no one behind, by ending poverty in all its forms and dimensions… Sustainable and inclusive urbanization… Environmental sustainability, by promoting clean energy, sustainable use of land and resources in urban development…”The focus is thus on combating poverty and inequality, and strengthening urban environments. From clauses 24 to 80 each of the three commitments is explained in more detail. For example, in clause 27, the New Urban Agenda affirms the pledge to “enable all inhabitants, whether living in formal or informal settlements, to lead decent, dignified, and rewarding lives and to achieve their full human potential,” a clause particularly salient in Rio.

The draft also acknowledges in clause 48 that in order to have inclusive “urban prosperity,” cities must “develop vibrant, sustainable, and inclusive urban economies, building on endogenous potentials, competitive advantages, cultural heritage and local resources, as well as resource-efficient and resilient infrastructure, promoting sustainable and inclusive industrial development, and sustainable consumption ad production patterns, and fostering an enabling environment for businesses and innovation, as well as livelihoods.” To make this possible, the document stresses numerous times the importance of “full and meaningful participation” and “people-centered urban development” in the planning process.

Cities must concentrate on growing their competitiveness equitably for their residents

A central focus in the New Urban Agenda is on adapting to globalization and urbanization through taking advantage of “sustainable and inclusive urban economies, by leveraging the agglomeration benefits of well-planned urbanization, high productivity, competitiveness, and innovation; promoting full and productive employment and decent work for all, ensuring decent job creation and equal access for all to economic and productive resources and opportunities; preventing land speculation; and promoting secure land tenure and managing urban shrinking when appropriate.”

There is a growing commitment to the “Right to the City”

In clause 11 of the draft, the document acknowledges the “Right to the City,” which it says means that cities should be built for all of their inhabitants. Within the New Urban Agenda, this means “equal use and enjoyment of cities and human settlements, seeking to promote inclusivity and ensure that all inhabitants, of present and future generations, without discrimination of any kind, are able to inhabit and produce just, safe, healthy, accessible, affordable, resilient, and sustainable cities and human settlements, to foster prosperity and quality of life for all.” It is important to note that the Zero Draft of the New Urban Agenda included numerous references to “equity” in cities, but the final draft includes this word just once. The New Urban Agenda envisions cities and human settlements as “fulfill[ing] their social and ecological function and the social function of land,” committing cities to implementing funding mechanisms and policy frameworks that minimize land speculation in clause 111.

Urban services like sewerage, transportation and affordable housing are common goods, and persons with disabilities are specially considered

Beyond affirming the right to the city, the New Urban Agenda marks specific urban services that must be equally accessible for all. In clauses 34, the New Urban Agenda affirms “to promote equitable and affordable access to sustainable basic physical and social infrastructure for all, without discrimination, including affordable serviced land, housing, modern and renewable energy, safe drinking water and sanitation, safe, nutritious and adequate food, waste disposal, sustainable mobility, health care and family planning, education, culture, and information and communication technologies.” Additionally, it commits nations to “promote appropriate measures in cities and human settlements that facilitate access for persons with disabilities, on an equal basis with others, to the physical environment of cities, in particular to public spaces, public transport, housing, education and health facilities, to public information and communication.”

Affordable, centrally-located, mixed-income quality housing is a critical part of creating better cities under the New Urban Agenda

The New Urban Agenda identifies this as a central theme and calls housing one of the interlinked essentials to “leave no one behind.” This was changed from the Zero Draft which called housing “inseparable from urbanization and a socioeconomic imperative.” Still, in clause 27, it calls for national governments to promote the “development of integrated and age- and gender-responsive housing policies and approaches across all sectors, in particular employment, education, healthcare, and social integration sectors, and at all levels of government, which incorporate the provision of adequate, affordable, accessible resource efficient, safe, resilient, well-connected, and well-located housing, with special attention to the proximity factor and the strengthening of the spatial relationship with the rest of the urban fabric and the surrounding functional areas.” Housing, it says, should be adequate, affordable, safe, well-located and linking to services like sanitation, public transportation, and jobs so it improves the conditions of the urban poor.

In regards to the informal sector, the Zero Draft of the New Urban Agenda stated, in clause 31, that “urban informality should be recognized as a result of a lack of affordable housing, dysfunctional land markets and urban policies. We must redefine our relationships with informal settlements and slums, including the informal economy, in ways that leave no one behind, taking into account that those areas are also engines for economic growth, prosperity, and job creation.” However, in the final draft of the Agenda, this language was removed.

This language starkly contrasts with the United Nations’ previous goals, which were to optimize for “cities without slums.” To reach this goal, the New Urban Agenda advocates in the new clause 31 for “housing policies that support the progressive realization of the right to adequate housing for all as a component of the right to an adequate standard of living, that address all forms of discrimination and violence, prevent arbitrary forced evictions, and that focus on the needs of the homeless.” This type of policy design is very different than the current Brazilian housing program, Minha Casa Minha Vida, which lacks this adaptability, except for its small sub-program providing for self-built housing by collectives and social movements, called Minha Casa Minha Vida-Entidades.

Further in the draft in clause 106, nations make a commitment to “promote housing policies based on the principles of social inclusion, economic effectiveness, and environmental protection. [Nations] will support the effective use of public resources for affordable and sustainable housing, including land in central and consolidated areas of cities with adequate infrastructure, and encourage mixed-income development to promote social inclusion and cohesion.” This is different to the Zero Draft’s language, which stated nations would “encourage mixed-income development to offset segregation, to secure land tenure in informal settlements, and to introduce efficient legal and technical systems to capture part of the land value increment accruing from public investment.”

Solutions to urban problems, including tenure, must be diverse and sensitive to local environments

The New Urban Agenda acknowledges that the needs of cities in the developing world are different to those of developed countries. There is specific recognition that the opportunities and potential risks of urbanization in areas like Latin America, Africa and Asia, are more extreme given their lack of infrastructure in the context of large populations and rapid transformation. In clause 17, it says “We will work to implement this New Urban Agenda within our own countries and at the regional and global levels, taking into account different national realities, capacities, and levels of development, and respecting national legislations and practices, as well as policies and priorities.”

In terms of housing, along with a general emphasis on flexibility in design, in clause 35, the New Urban Agenda advocates for a greater variety of land tenure solutions “develop fit for-purpose, and age-, gender-, and environment-responsive solutions within the continuum of land and property rights.” The draft then states later in clause 107 that the New Urban Agenda will promote “access to a wide range of affordable, sustainable housing options including rental and other tenure options, as well as cooperative solutions such as co-housing, community land trust, and other forms of collective tenure, that would address the evolving needs of persons and communities, in order to improve the supply of housing, especially for low-income groups and to prevent segregation and arbitrary forced evictions and displacements, to provide dignified and adequate re-allocation.”

Implementation mechanisms are the key to success

Aside from policy outcomes, in clause 81 the New Urban Agenda acknowledges that a large problem with urban policies is a lack of implementation and calls on national and local governments to create stronger accountability and implementation mechanisms. In Rio, where the once-award-winning Morar Carioca program seems unlikely to reach a tiny fraction of its goal of urbanizing all favelas by 2020, this acknowledgement is critically important. If Rio plans to follow this New Urban Agenda, it will have to work hard to take its well written laws and implement them correctly.

Clause 86, the New Urban Agenda calls for an “integrated approach to urbanization that includes the effective deployment of appropriate and progressive urban and housing legislation and policy frameworks, sound and innovative financing mechanisms, appropriate land governance, quality urban planning and design, and mechanisms for strong civil society engagement in decision-making, as well as implementation and monitoring of urban development.” To make this happen, the draft suggest mechanisms like multi-stakeholder partnerships, community assessments, cooperation mechanisms, consultation and reviewing mechanisms and platforms for implementation that create shared ownership and responsibility.

Clause 86 calls for an “the effective implementation of the New Urban Agenda in inclusive, implementable, and participatory urban policies, as appropriate, to mainstream sustainable urban and territorial development as part of integrated development strategies and plans, supported, as appropriate, by national, sub-national, and local institutional and regulatory frameworks, ensuring that they are adequately linked to transparent and accountable finance mechanisms.” To make this happen, the Agenda suggests mechanisms like multi-stakeholder partnerships, community assessments, cooperation mechanisms, consultation and reviewing mechanisms and platforms for implementation that create shared ownership and responsibility.