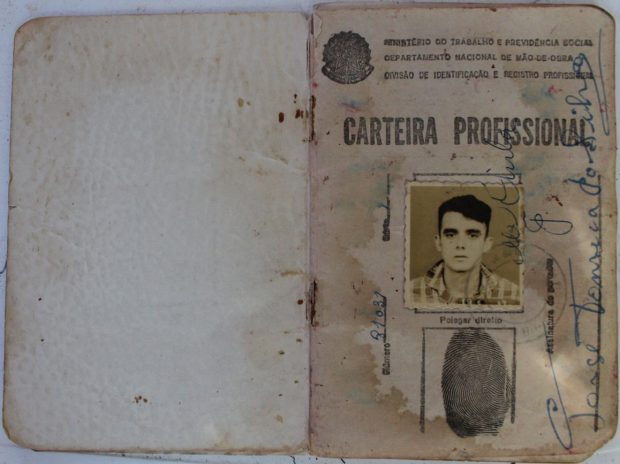

Orlando “Folha Seca” (Dry Leaf) Pereira da Silva, the first gardener to be formally employed by Rio de Janeiro’s Botanical Gardens, died on June 1 at the age of one hundred. Folha Seca is remembered with great pride by family and friends in his community of Horto Florestal. He lived in Horto with his family, who still live there, since the Botanical Gardens gave him permission to build a house there in order to live close to his work. Today the Horto community is over 200 years old.

On July 25 the Botanical Gardens held a tree planting ceremony in memory of its “oldest gardener,” honoring his nearly 70 years of work. The event was received with mixed feelings by Horto residents, since the Botanical Gardens’ Research Institute has attempted to evict Folha Seca from his home, and continues to threaten the housing rights of his family.

RioOnWatch interviewed Jacqueline da Silva about her experience as a granddaughter of Folha Seca and daughter of Jorge Fonseca da Silva, a seed collector at the Botanical Gardens who died when he fell from a tree while collecting seeds at work. Jacqueline shared her perspective on the memorial for her grandfather, the fight for housing rights in Horto, and the historical relationship between Horto residents and the natural world surrounding them.

RioOnWatch: How long have you lived in Horto Florestal?

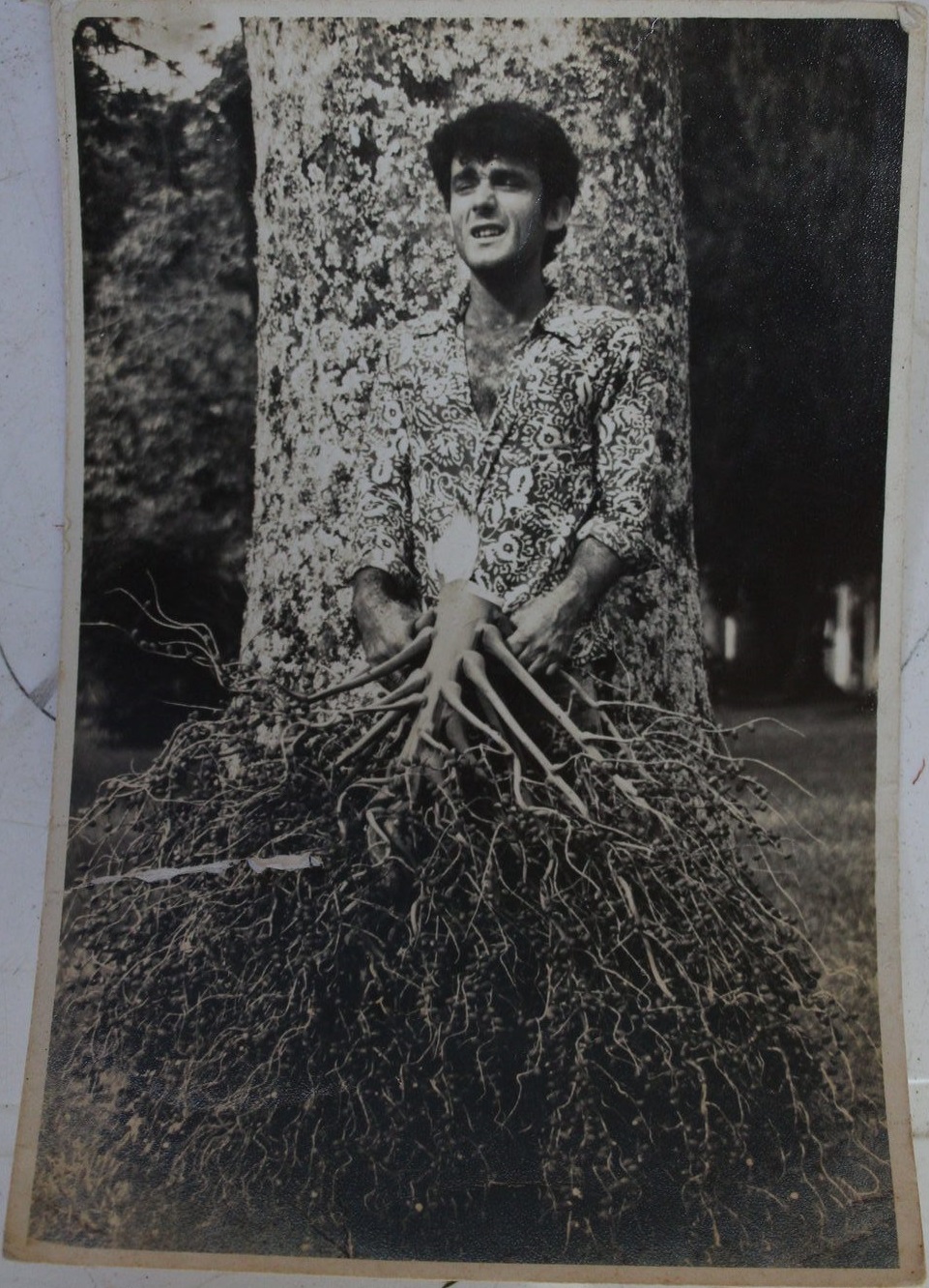

Jacqueline: I’ve lived here for 47 years. I was born and raised here in Horto. My father died in the Botanical Gardens. He was a seed collector. He died when he was 29 years old, after falling from a tree inside the park. Everything I learned, I learned from him, even though I was very young when he was still alive. My whole family has always worked in the Botanical Gardens. That’s why I know the names of all the plants, without ever having studied them. I make medicines and formula from them. It’s in my blood. I inherited it from my father and from Folha Seca, who died recently.

Jacqueline: I’ve lived here for 47 years. I was born and raised here in Horto. My father died in the Botanical Gardens. He was a seed collector. He died when he was 29 years old, after falling from a tree inside the park. Everything I learned, I learned from him, even though I was very young when he was still alive. My whole family has always worked in the Botanical Gardens. That’s why I know the names of all the plants, without ever having studied them. I make medicines and formula from them. It’s in my blood. I inherited it from my father and from Folha Seca, who died recently.

RioOnWatch: Have you worked in the Botanical Gardens?

Jacqueline: No, I work for myself. I have a landscaping business and I do landscaping work. I do tree treatments. I do all kinds of work related to the environment.

RioOnWatch: There’s a narrative coming from the media and the Botanical Gardens’ Research Institute that characterizes Horto residents as ‘invaders’ who ‘damage’ the forest. How do you respond to those charges against the community?

Jacqueline: They say that about us because really they want to sell this land, because it’s about real estate speculation.

But the people here, most of them, are expert gardeners. They all know something about plants. So I think the Botanical Gardens is being unfair. [The] justice [system] is being bought by the elites who live around Horto. They’re trying to turn people against us. We do our best to take care of our community. We look after the plants, clean the river, do community service work, clean the paths, take care of the trees… we plant coconut palms, trees such as pau-mulato trees. This tree right here [in the community] is 80 years old. Not even the Botanical Gardens has one of these. At one point they wanted to come take my tree. Isn’t that crazy? A tree my father had planted. They wanted to come in here and take my tree away. It’s an abuse of the power they think they have.

So they cut down my life [since my father died at work] and my siblings’ lives. I couldn’t go to school because my mother was a widow and illiterate with three children. They took away my right to be someone in life, and now they want to take my right to live here and raise my children. That’s crazy.

And the people who live here don’t harm the Botanical Gardens at all. On the contrary, the park only exists today because there were people who built it. And it wasn’t the rich elite—who stroll through the park, or have their nannies take the kids there—who built the Botanical Gardens. The ones who built the Botanical Gardens were the workers, who are dead now. Either they’ve already died or they are dying because of the pressure coming from the park’s new president, Sérgio Besserman.

So we fight. And we won’t let the residents of Horto be treated unfairly. I have four dogs and three children, including one child with special needs, and a mother with Alzheimer’s. Where else would I live? And where is my life story? Everyone was born and raised here. So we’re not just talking about removing you from your house and giving you another house. It’s your life story they want to erase. You can’t just erase someone’s life story.

Now they want to kick us out of here, because poor people are ugly and don’t go well with the mango trees and orchids. The poor don’t go well with anything. The poor go nicely with Avenida Brasil and concrete. And the rich can build mansions all around the forest. If you look at night, the area above the forest is completely lit up, full of mansions, and the “Canto e Mello” gated community, which was given its land by the federal government. Given! The same exact situation of Horto residents: they received the land, it was given to them. They paid through a compensatory measure, by planting the forest. So why not do the same for the people of Horto? Who have already been planting here their whole lives?

RioOnWatch: Was your family compensated for your father’s death?

Jacqueline: Not at all. At the time of his accident, my father was assigned to the INTS (National Institute of Support for Research, Technology and Innovation Under Public Management). When he fell from the tree and fractured his spine, the Botanical Gardens scrapped his work papers. He lived at the hospital for another year, as a paraplegic. He lost teeth, he lost everything. He deteriorated until he finally died at the age of 29. He didn’t have any support from the Botanical Gardens.

Where was I going to live once they took my father’s life from him? If my father had lived, I would have studied, I would have been a botanist. But how was I supposed to study? I was living in disgraceful poverty on my mother’s pension. They put my father on INSS (Social Security) so she received the minimum salary, the rural minimum salary. Where was I going to live? Under a bridge? After I had built my life here?

RioOnWatch: What’s your perspective on the Botanical Gardens’ tribute to your grandfather, Folha Seca?

Jacqueline: I didn’t participate in that tribute because, to me, it was a joke. How can you honor someone while taking his relatives to court? What kind of tribute is that? I didn’t see anything glorious about that tribute. A real tribute would be to stop the legal process against the relatives of Folha Seca, who died at the age of one hundred and who lived a hundred years for the Botanical Gardens. Stop all the legal processes now. That would be a real way to pay tribute.

RioOnWatch: Is there anything else you’d like to add?

Jaqueline: I would like to comment on the indignity and lack of respect with which the residents of Horto are treated. Horto only exists because of the people who live there. The real invaders are them [the Botanical Gardens]. They’ve swallowed up half of the children’s school yard.

They just want to get a piece of this land because they want an affluent neighborhood, an affluent area, in Rio de Janeiro’s South Zone. I miss [former Rio governor] Leonel Brizola, who let people live on the Parque da Cidade land. If we had a Brizola in Congress or government today, the residents of Horto wouldn’t be going through this. But there is no decent, honest politician to take up our cause. We had the promise of Lula, we had the promise of Dilma, but with that guy Temer, we have no promises. We had promises, but what happened? Nothing. The paperwork disappeared in Brasília. How does paperwork disappear in Brasília, people? Papers signed by the former president. The paperwork just disappeared. Isn’t that strange? So who do I talk to? Now we can only count on international help, which comes from you.

They just want to get a piece of this land because they want an affluent neighborhood, an affluent area, in Rio de Janeiro’s South Zone. I miss [former Rio governor] Leonel Brizola, who let people live on the Parque da Cidade land. If we had a Brizola in Congress or government today, the residents of Horto wouldn’t be going through this. But there is no decent, honest politician to take up our cause. We had the promise of Lula, we had the promise of Dilma, but with that guy Temer, we have no promises. We had promises, but what happened? Nothing. The paperwork disappeared in Brasília. How does paperwork disappear in Brasília, people? Papers signed by the former president. The paperwork just disappeared. Isn’t that strange? So who do I talk to? Now we can only count on international help, which comes from you.

The help we do have here is from the people. It’s in people getting together and building a movement together. It’s ugly when we put an old refrigerator in the road. But it’s the only defense we have, and it’s not really a defense. Because when the police come, they beat everybody up. We know that it’s not really going to do us any good, but symbolically we feel safer with it there. It does help if it becomes a source of strength, a kind of support, greater than the power we actually have. There are human rights, housing rights, animal rights, and senior citizens’ rights. We need to bring all these rights together on behalf of the residents of Horto. If we don’t, we’ll be massacred by the elite of Rio de Janeiro’s South Zone.