Some people think Catholicism is retrograde and refuses to talk about the complexities of contemporary society. However, two initiatives stemming from social movements linked to the Catholic Church in the Baixada Fluminense region, just north of Rio de Janeiro and comprising the bulk of its metropolitan region, show how this discourse can be mistaken. Through the work of the civil society forum Grita Baixada and religious representatives from the municipalities of Baixada Fluminense, what was previously considered taboo is now an inevitable topic of discussion. For the first time in their histories, the Dioceses of the Nova Iguaçu, Duque de Caxias and São João de Meriti municipalities promoted public debates about the possibility of decriminalization and/or legalization of drugs.

On two occasions, on October 26 and November 18, 2017, the dioceses organized visits by renowned public security specialists, defenders of a non-punitive approach to the law for users of illicit drugs. The debates were part of the “Drug Policy and Violence: A Necessary Debate” seminar. Without fearing value judgments, generating understanding was the primary intention of the religious leaders who promoted the debate. “I always consider it very valid to inquire into the real problems our society lives and faces. It is the Church’s duty to want a better world, to reflect seriously on the effects, the causes and, above all, the roots of a system that oppresses, humiliates and kills. Will filling the prisons for small crimes committed by young people be the right way to achieve more peace and security?” asked Dom Luciano Bergamim, bishop of the Nova Iguaçu Diocese, during the seminar in October.

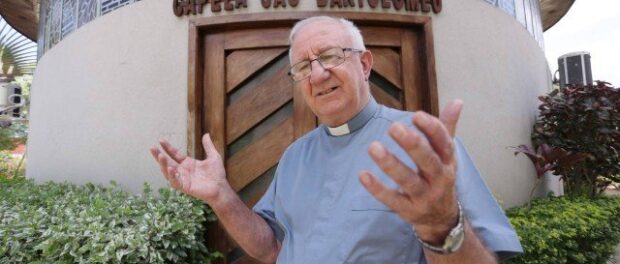

The discourse of the Catholic priests remained in tune. “The problem of drugs, trafficking, and the violence associated with them is very serious and affects the whole of society. We currently have no prospect of emerging from this crisis. It is clear that the current drug policy is a failure: so many young people being murdered, especially black youth, police officers being killed, overcrowded prisons that are schools for crime,” said Father Toni, coordinator of the Duque de Caxias/São João de Meriti Diocese, who took on the role of mediating the roundtable of the second seminar, which took place in November.

While mediating the first seminar in October, coordinator of the Grita Baixada Forum, Adriano de Araujo, commented on Law 11.343/06, the so-called Drug Law, which for many is “to a great extent responsible for the increase in Brazil’s prison population,” he said. According to figures provided by INFOPEN—the Ministry of Justice’s information system on Brazilian prisons, including data on infrastructure, the prison population, and prisoners’ profiles—in 2005, 9% of incarcerations throughout the country were related to narcotics. This number jumped to 28% in 2014. “In theory, the law has toughened the punishment for traffickers and softened it for users. In fact, the main change brought about by the law was that traffickers and users should be treated differently. However, this distinction is not objective. In practice it is up to the judge (or police officer) to decide in which category of crime a case will be placed,” explained de Araujo.

Professor of criminal law and criminology of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), Luciana Boiteaux, was invited to both debates. She said that the prohibitionist character of the Brazilian Judiciary emulated the historical context of the United States. “Political and diplomatic negotiations created the so-called prohibitionist policy. There was never a study on which substances should, in fact, be banned. There was no conference with specialists to assess the risk of these products. On the other hand, this prohibition policy we have today is very similar to the one that began in the USA in the 1960s. The idea is to prohibit, criminalize, and give the police the task of repression. The campaigns were: ‘Our children are dying and we have to wage a war on drugs.’ But it’s a war against people. The motto was ‘don’t use drugs, you will be arrested.’ Everyone thought that this drug policy would work,” Boiteaux explained.

One of the consequences of excessive prohibition, according to the researcher, is the difficulty of creating more humanized public policies for users. “The user needs support from family, from churches and also from the State. We need to provide a policy that welcomes them, providing housing and therapeutic processes. The profile of the imprisoned trafficker is of young people caught with laughable amounts [of drugs on them]. People are being arrested with a gram of cocaine. Almost no one is arrested for carrying a weapon, with quantities that the law determines [to count as trafficking]. This conversation needs to echo in public policies,” said the specialist.

Another participant in the two editions of the seminar was retired Military Police colonel, Ibis Pereira, a firm defender of the demilitarization of the Military Police, as well as a fierce critic of the racism that prevails in institutions of social control. “The great majority of crimes that result in these arrests are homicide, robbery, and deaths resulting from conflicts against police intervention. In absolute numbers, no democracy kills more than ours,” the officer explained.

He also harshly criticized the lack of investigation into and surveillance on arms trafficking, which he said was much more lethal than the parallel drug trafficking market. “The Baixada Fluminense is one of the territories with the highest number of homicides in the country and we do not have a plan to reduce these numbers. About 56% of murder victims are between 15 and 19 years old. The Federal Police conducted research in 2012 and came to the conclusion that there are at least 16 million weapons circulating in the country that are under no type of control. And who will be the victims of these weapons? The black and the poor,” said the colonel.

The third guest of the two editions was Ricardo André de Souza, deputy coordinator of Criminal Defense at Rio’s Public Defender’s Office. Reporting on the prison population in the context of the criminalization of drugs, he said: “The last survey by the Institute of Public Security (ISP) in 2016 indicated 51,000 prisoners for only 27,000 places. That is to say, the levels of incarceration do not solve public security problems and are expensive investments. Prisons are replaced by public jails, but they serve only to inflate the number of prisoners. The last two prison units were built in São Gonçalo in 2013. Each of them cost R$30 million (around US$9 million) and has a capacity of 800 places. A minimal reduction in overpopulation would require building 30 more prisons at a cost of more than R$1 billion (around US$300 million).”

And as pointed out by the Civil Police delegate, Orlando Zaccone, who took part in the first edition of the seminar: “Only 8% of the infraction acts by minors are violent cases. Amnesty International has investigated 20 countries that have the death penalty. In one year these countries recorded 685 deaths. The police in Brazil, in the same period and in only the two states of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, recorded 976 deaths [at the hands of police]. Most inquiries into cases of police killings are labeled as ‘resistance to arrest’ and are archived, as it is enough for the police to say they acted in self-defense. And this justification always happens in favela communities, never in rich or middle-class neighborhoods.”

This article was written by Fabio Leon and produced in partnership between RioOnWatch and Fórum Grita Baixada. Fabio Leon is a journalist and human rights activist who works as communications officer for Fórum Grita Baixada. Fórum Grita Baixada is a forum of people and organizations working in and around the Baixada Fluminense, focusing on developing strategies and initiatives in the area of public security, which is considered a necessary requirement for citizenship and realizing the right to the city. Follow the Forum Grita Baixada on Facebook here.