A viaduct full of cultural activity that attracts local youth, and an urban park for leisure and playing sports. What is finally a reality in Madureira, in Rio’s North Zone, is the aspiration of many residents from other neighborhoods, who should not have to cross the city just to access recreational and cultural spaces, which are heavily concentrated in the South Zone and Centro, in addition to their long daily commutes to work.

Tired of waiting for formal facilities where they can socialize and be creative, these residents have been organizing themselves to occupy squares, sidewalks, and spaces under viaducts with activities ranging from parties to workshops and from movie screenings to contests (for rapping, passinho, skateboarding, and graffiti), redefining transit areas and transforming them into spaces of coexistence, also increasing the feeling of safety in the areas. Some examples of this include the Praça Semente Viva project, which provides spaces for recreation and interaction and which was built via a community mutirão (collective action) in Babilônia; the Leopoldina Organic Festival, which occupies several squares in the North Zone (including in Alemão, Manguinhos, Vila Cruzeiro, and Vigário Geral favelas), serving simultaneously as space for experimentation and socializing around culture and agroecology; and Favela Cineclube, which exhibits short and feature-length films in a square under an overpass in Providência.

In the case of urban parks, popular mobilization is not enough to build a park with all the required infrastructure, but mobilization still has an important function in putting communities’ demands for parks on the agenda and in holding public authorities accountable to their promises.

Under the viaduct

Realengo, a neighborhood in Rio’s West Zone, was immortalized in the song “Aquele Abraço” by Gilberto Gil, with the line “Alô, Alô, Realengo” referring to where Gil was imprisoned during the dictatorship. Today, it is the setting of two simultaneous movements. On one side, the Realengo Viaduct Cultural Space was created underneath the viaduct that provides access to the train station. The space has been decorated by local graffiti artists with a number of works by Oberdan Mendonça, the founder of the occupation. It’s on an officially nameless street that the occupiers want to name after Walter Fraga, a violinist and luthier who lived in the region. Around three years ago Mendonça and his companions spearheaded the “City Viaduct Circuit” initiative, mapping the city’s viaducts and proposing cultural activities there. “Instead of waiting for invitations to go to other territories to run activities, we decided to revive this public space to boost the neighborhood’s cultural network and create exchanges with other territories,” Mendonça explained at the time.

On Tuesdays, there are cultural events with rap battles. On Fridays, baile charme dances. Once a month the Escola de Barbeiros (Barbers’ School) offers free haircuts. The space was also one of the locations for the Cinema Zone Festival, which runs across several West Zone territories. Fernanda Távora, a local resident and one of the festival producers, says that the activities are a cultural and also political alternative “in a neighborhood that has nothing.” She explains: “Realengo doesn’t have many cultural spaces, there is no theater. There is just a cinema that shows blockbuster movies. There is no museum. We have no library, no bookstore. We may not be starting a revolution, but what we are doing is political. We are drawing attention to the fact that there are people in the West Zone who produce and consume culture.”

Távora recalls a situation that illustrates this well: “A man and a woman turned up here one day, watched the film, participated in the debate, and then told us how they’d actually been going to the South Zone to attend the theater or the cinema, but then they missed the train [which goes over the viaduct where the event took place]. As it was the weekend, the next train was going to be a while and they would have had to wait too long. [When they passed our movie screening they stopped to watch. After the film was shown] the man shared that he himself had produced a video, with a samba musician, talking about Bangu. So we opened [his video] on YouTube and watched it together. It was a really cool moment.”

For Távora, besides the cultural and political dimensions, the occupation of the space is a matter of security and identity: “This space has always been abandoned. Any events that take place in the viaduct create more security for local residents. This area is known for having a lot of robberies, it’s a place [that was] very deserted, dangerous. The people who occupy the space leave it clean, they decorate it with street art, so that the space is no longer dark and colorless. We have also tried to start a community garden. When you enter there is a plot on the right. People go there to take care of the plants. It’s also a way of building a sense of community, a sense of belonging to the territory, to understand that this space belongs to everyone. This space is yours, it’s part of the place where you live, it’s not just any old place you walk by, not just a place to transit through.”

After doing the city government’s work in terms of providing cultural spaces, to continue their activities the organizers of these types of events often seek the City’s support in the form of grants and funding designated for cultural development. These, however, are scarce in the context of the present administration, which has had a troubled relationship with culture, especially popular and street culture. “We depend on grants. We were awarded one from Rio Films to hold a festival. There is no public policy, nothing, that gives financial support to organize the festival. There are many people who do this, they start on their own and then get support from somewhere, from a tattoo shop, a restaurant, but nothing from the government,” says Távora.

On the park

On the other side of Realengo, a little more than a mile away lies an abandoned piece of land where an army cartridge factory operated until it was deactivated in 1978. For many years now, residents have been demanding that the Green Realengo Park be built on this land, creating a public use for an area that is, after all, public. The Federal Institute of Education, Science, and Technology (IFRJ) campus, a benchmark in public education in the city, occupies one end of the land, but the rest of the space has been abandoned since the 1970s. POUPEX (Savings and Loan Association), which is managed by the Army Housing Foundation, currently owns the land and wants to use it to build military housing units. However, the demand for more military housing is questionable given that this neighborhood is already right next to Deodoro and Vila Militar and is also where, in the 1980s, a condominium built for military personnel was not fully occupied, resulting in some units being sold to civilians.

POUPEX’s plans include a green area that would be accessible to local residents as a social space for the neighborhood. The residents, however, dispute the proposal. Besides the fact that the area would be much smaller than the park they are advocating for, they fear that access would be bureaucratic or even restricted because it would be a military area. The environmental preservation of the region is also a concern for the movement members, as the construction of buildings could damage the local environment.

Residents say the park would improve cooling in the neighborhood, which shares super high temperatures with neighboring Bangu in the summer, and would meet a need for shockingly scarce green areas in the neighborhood between Pedra Branca Park and the Serra do Mendanha. Leandro Fraga, a 47-year-old local resident, is part of the Green Realengo Park Popular Movement, which brings together residents and more than 22 institutions. He says: “There is no recreational area where we can bring people visiting the neighborhood, the elderly and children. The hills around here are steep, they are not suitable. As a father I can’t take my children there. There is no Botanical Gardens, no Parque Lage or Aterro do Flamengo [like in Rio’s South Zone] here. An ecological park would bring peace, tranquillity, harmony. The neighborhood would have a different ambience. It could even reduce the impact of floods, supporting drainage in the surrounding streets.”

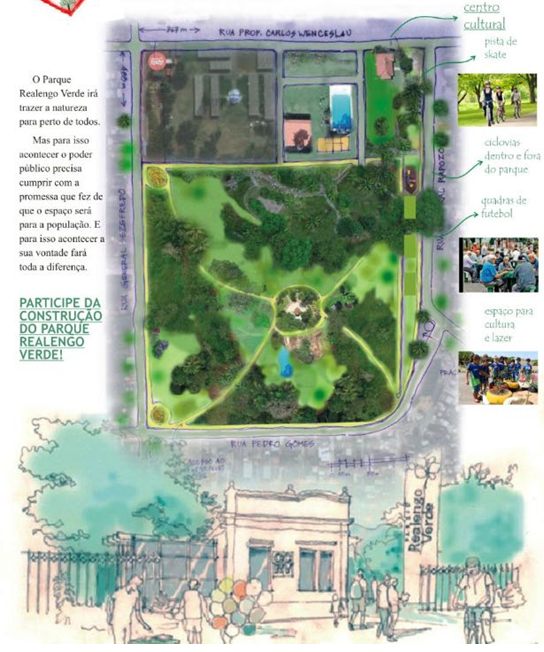

What’s more, for the people fighting for the park, it is not just a question of well-being and leisure. The occupation of the abandoned public space is also a matter of security, since the abandoned facilities of the old factory end up being used as a hiding place by criminals. And leisure is not just restricted to the existence of a physical space. The project that the residents submitted to the city government, prepared by Professor Luiz Otávio Pessôa from Estácio de Sá University, includes sports fields, a soccer pitch, a cycle path, a skateboard park, an outdoor gym for seniors, a playground, kiosks, picnic areas, and a water feature, in order to meet the demands of the residents. In addition, the park would facilitate pedestrian access to Realengo’s station (and, consequently, to the viaduct’s cultural space).

The importance of the park is enhanced by the fact that leisure options in the city of Rio are distributed very unequally. Mayor Marcello Crivella’s own administration recognizes this in its Strategic Plan, stating that there is “a disparity in the concentration of urban parks in the city, which are mostly located in Planning Areas 1 and 2,” which correspond to Centro and the South Zone. The Plan also states that “in Planning Area 5 – AP5 (West Zone), on the other hand, there is a significant shortage of parks and leisure spaces, while large areas, often threatened by irregular real estate pressure, are environmentally fragile and require a more careful consideration of their use.”

However, in spite of this analysis, which was accompanied by the Realengo Park being announced in both the Strategic Plan and a city government decree on January 1, 2017, there is still no sign of the park being implemented. There is also no sign of the other parks promised to be similar to Madureira Park, such as the Campo Grande Park, announced in October 2017, the City of God Park, announced four days after a police operation with intense shootouts in the area, and the Maré Park, announced after the death of Marielle Franco, both in March 2018.

In a consultation meeting in the neighborhood in March 2017, which was attended by the mayor, residents voted to create the park in place of the construction of a condominium. In the meeting, Crivella emphasized the importance not only of the park, but of participatory planning: “With Realengo Park being chosen by the majority, we will be contributing to the whole region. Because it will be a spectacular recreational area, a democratic area, an area that the young, the elderly, the poor, the rich are all welcome. Something extraordinary that we will also leave behind for our grandchildren, great-grandchildren and generations to come as an achievement of our generation.” For resident Leandro Fraga, however, Crivella’s speech was just empty words: “The mayor is not solving anything—either he pleases the majority, which is the population, or he pleases the bank directors, real estate interests, the colonels.” The mayor said he would meet with the Army to discuss the transfer of the land to the City and that he would return to continue working on the project, but in reality he has never returned to the neighborhood.

Instead, at the end of last year the proposed Complementary Law 32/2017, signed by Crivella, was presented to the City Council, and it is far from what the residents demanded. The proposed bill calls for POUPEX to donate 54% of the land for the City to build the park in exchange for building the condominium on the remaining 46%. In exchange for POUPEX’s concession, the project allows the condominium height restrictions to extend from eight floors (as determined by the Master Plan) to 11 floors, “in order to liberate the largest possible area for the implementation of a park, a project of great social importance.”

The Realengo Regional Administration’s Facebook page ran an online poll and 80% chose the option that provided for the construction of the park on the entirety of the land. The result justifies the motto that was then adopted by the movement: “100% Green Realengo Park.” The bill is undergoing amendments and has not yet been voted on. It was the topic of one public hearing on June 8 and another public hearing is scheduled for June 25.