While the failure of the Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) model had already been signaled years ago by residents, researchers, civil society organizations, and Rio’s violence and mortality rates, only in 2018 did public authorities indicate the partial dismantling of the UPPs in the context of the federal military intervention in Rio’s public security. The cabinet responsible for coordinating the intervention indicated the intention to relocate UPP officers to police departments linked to local battalions in order to cover the same areas. This would bring an end to proximity policing with bases in favelas and mark a return to the old model characterized by periodic raids. More recently, in February 2019, a bill providing for the complete extinction of UPPs began to move through the Rio de Janeiro State Legislative Assembly (ALERJ), gaining approval in the first round of voting.

In light of the deactivation of some units in 2018, former Military Police spokesman Major Ivan Blaz said that police officers can now act “more freely” and “the troops do not need to be tied to a physical location.” For residents, on the other hand, the end of UPPs could present the opportunity to resignify the physical spaces that the bases once occupied in favelas.

While some bases are physical buildings constructed by the police to house UPPs, in some cases, UPPs occupied preexisting buildings or public squares, and in others, they simply installed the bases in containers. In all cases, the question remains: what existed at the site before being relocated to make way for the UPP? What could now take its place following the dismantling of the UPP? For example, André Constantine, former president of the Babilônia favela’s residents’ association, said that a house was removed to construct the UPP building and the ousted residents left the space with unsatisfactory compensation. The UPP continues to operate, but for him, the space would ideally house a daycare center or school.

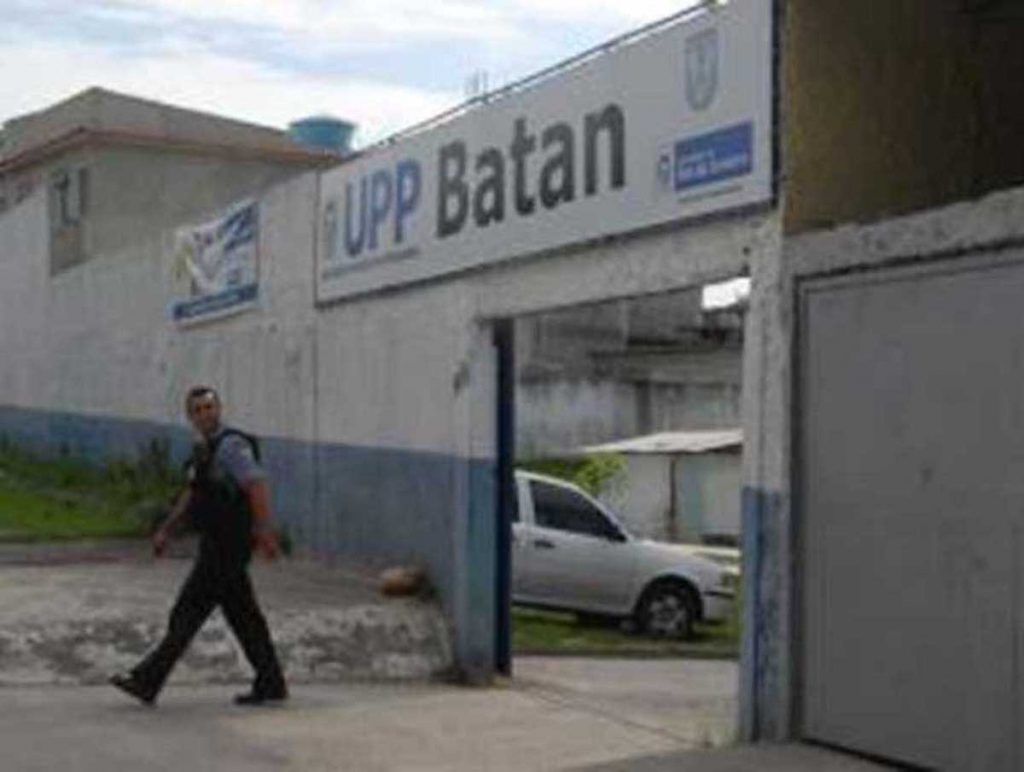

Of the 38 UPPs installed between 2008 and 2014, the first units to be deactivated (in June 2018) were in Vila Kennedy, which was regarded to be the intervention’s test lab and was where the military presence was perhaps most strongly felt; in Mangueirinha, Duque de Caxias—the only UPP located outside of the capital city; and in Batan, the second favela to receive a UPP and the first in the West Zone.

At the time, the installation of the Batan UPP came as a response to an incident in which journalists from the newspaper O Dia were tortured for seven hours while spending a few days in the community to produce a story about residents and the militias that operated there. Becca Vieria—a local producer and resident of Batan—says that initially, the UPP operated out of the large abandoned house where the journalists were taken hostage: “It was a militia site and when the UPP arrived, they occupied the space. A few years later, the property owners went to court to repossess the house and the government was forced to create another base in a public square closer to Gericinó.”

“The owners asked for the large house back but left the space open to social projects—swimming and water aerobics for elderly people and martial arts classes for children,” she recalls. This case is emblematic of the act of resignifying space: social projects came to occupy a space that had once been an abandoned house, a crime scene, and a police base. “The police, in turn, took up much of the public square to build their base.” In other words, unlike the owners of the large house, instead of creating leisure options for the community, they made it impossible to do so. “Odebrecht (construction company) was responsible for the construction of the new base. Due to media scandals, construction was halted for a long time. Now [with the deactivation of the UPP], it is closed but it is still under the control of the 14th Battalion, whose officers usually leave a police car out front. The space is well structured with rooms and air-conditioning. This ‘white elephant’ created by the government has no social or cultural use,” laments Vieria.

Her dream is to have an activities space for the community’s youth to support and develop their skills in order to break the cycle of children joining drug trafficking gangs: “We have a playground in the community but residents oversee it, and you have to pay to use it. You have to pay to use a public space! And in the UPP building, there’s another space that could be used by the community. We could make a calendar. Each day, a different project could use the space during their time slot. Several projects could use the space so that Batan becomes a cultural hub.”

After the first wave, it was City of God‘s turn to have its UPP removed in July of last year. “If we were able to concentrate there, like in a study center, that would be great! We don’t have a library here in City of God so it could be a study space and, who knows, maybe even host a pré-vestibular [college entrance exam preparatory course]?” dreams Nathan Borges, a young theater instructor and DJ producer from City of God.

The São Carlos UPP was also deactivated in November, followed by the Camarista Méier UPP in the North Zone and the Caju UPP in Central Rio in December. The dismantling of the Cerro Corá UPP was announced in December, as was its change to be included in the area covered by the Santa Marta UPP (though this has not yet been carried out).

A resident of Cerro Corá who prefers to remain anonymous says that the UPP there was different, given that there was no drug trafficking in the community. Its installation was motivated by a robbery that occurred in the area. “People from here have taken action to inform residents, making handouts about the police and the rights and duties of citizens who live in the community and of police officers so that we can try to mitigate the police abuses that we know do happen,” he says. All of the UPP’s bases in the community were in containers—three on the grounds of Silvestre Hospital and three others along the cable car line that goes to Christ the Redeemer—”for tourists to see, really,” in the opinion of another resident.

“We already knew that the UPP would end after the mega-events. We knew since the beginning that the project would fail,” says the first resident. He continues: “We need services, public policies. Every public square in Rio de Janeiro has a street cleaner, but here in the favela, there isn’t one. We went through an upgrading process via Favela-Bairro for more than twenty years but it was not maintained.” He would rather see garbage collection points and sewage pipes in place of police bases.

Even in the favelas in which UPPs still function, residents say that their own hopes don’t align with reality. Fatinha Lima, a resident of Providência and founder of the Favela Cineclub, criticizes: “[The UPP building is] a huge building, which, despite some workshops and courses offered, is underutilized as part of a policy that never worked anywhere in the world. We know of many successful examples of fighting violence and promoting the population’s rights through education, information, art, and culture. This is what should exist in the city’s favelas and peripheries.” In this sense, she dreams: “I want to transform the Providência UPP into a school for audiovisual production.”

Andreia Nogueira—a resident of Cantagalo and doctoral student in social work at the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (PUC-Rio)—says that the building where the Pavão-Pavãozinho/Cantagalo UPP was housed was built in the 1980s under former governor Leonel Brizola. It was originally built to house local families whose houses were at risk of collapsing. “The building was completely derelict. There was a cistern on the ground floor without a lid—very close to the panel where the electricity meters were located—with exposed wiring. There was no handrail. In fact, the building was in a state of chaos. However, instead of carrying out upgrades to improve the buildings for residents to live in, they decided to move them to the next building, which had been built to house residents displaced by the Growth Acceleration Program (PAC).”

The building was then remodeled as part of the PAC public works, even though it was not included in the original plan. Instead of welcoming back the families, the building was handed over to the UPP: “When visiting Pavão-Pavãozinho/Cantagalo to see the works, [former governor] Sérgio Cabral asked where the captain who was slated to command the UPP wanted to locate the base. He pointed to the building constructed by Brizola,” she says.

For Nogueira, the building should be utilized for culture and leisure and to engage the community’s youth. She says that initiatives like this do exist in the community but many of them are concentrated in one specific place—the space formerly known as Criança Esperança, now administered by Viva Rio, located right next to the UPP base. “Despite housing several social projects, when it was administered by Criança Esperança, the space was tightly controlled and not fully utilized. There were also problems with the administration.”

In the space occupied by the UPP, she imagines a Citizenship Center or a Park Library, which currently doesn’t exist at all in the community. “Our young people need to be encouraged to practice reading, to exercise citizenship, and to engage in educational practices that will propel them towards a liberated future.” In the case of the Citizenship Center, some of the initiatives that she envisions could take place in the space include a community preschool, psychological counseling, lectures on social rights, tutoring classes, guidance on various forms of violence and how to deal with them, and activities to strengthen community organizing and participation. “Of course, everything would be free and ideally run entirely by residents themselves, with each person giving a little,” she concludes.