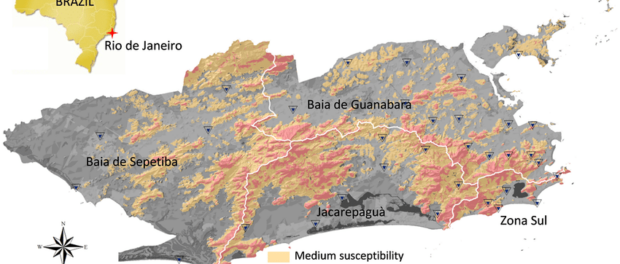

During the first few months of 2019, the city of Rio de Janeiro experienced two major rainfall events that led to a total of 17 deaths and left hundreds homeless. With sequential rain disasters becoming increasingly commonplace, Rio de Janeiro is already experiencing dramatic impacts from climate change. In the wake of these perennial events, proper landslide and flood mitigation and prevention has gained heightened attention (attention alarmingly unmatched by government budgets).

This series on rainfall disaster risk and mitigation sheds light on the natural disaster prevention systems currently in place in Rio and their effects on communities across the city. Part one of this series took a look at the definition of risk and the history of landslide and flash flood prevention and warning tactics in place in Rio, namely the “Community-Based Alert and Alarm System.” Part two, below, examines the potential applicability of an alternative early warning system using acoustic emissions.

As explained in part one of this series, Rio de Janeiro employs a network of rain gauges throughout the city to monitor rainfall and mitigate the effects of rain-induced natural disasters. The Rio Alert network, implemented in response to a series of deadly landslides in 1996, was born in 1997 and enhanced two years later with Doppler radar and a team of Geo-Rio meteorologists. In 2011, the system was updated again with a new audible siren system and a complete mapping of the city’s designated “areas of risk.” This system aims to warn favela residents of significant precipitation roughly two hours prior to a potential disaster, such as a flash flood or landslide.

The system is inadequate for a number of reasons. First, the rain gauge network measures rainfall levels within a set timeframe rather than tracking soil movement in the at-risk ground. This is insufficient, given that landslides have taken place in Rio at levels below determined alarm-triggering levels (note the 2019 landslide in Morro da Babilônia, in the city’s South Zone, when two were killed and alert sirens did not deploy). Second, once rain gauge thresholds are reached, the community is not immediately warned—a preliminary counsel between the Civil Defense and Geo-Rio leaders decides whether or not the risk is large enough before sounding an actual alarm. Third, the City’s financial missteps have placed communities at greater risk: spending on flood prevention measures has fallen 71% under Mayor Marcelo Crivella. While the mayor has reportedly made efforts to secure financing in preparation for the upcoming Rio summer ahead of 2020 municipal elections, he also froze payments for all public servants on December 17. With the rainy season fast approaching, the City needs a cost-effective, community-run alternative.

An Alternative in Acoustic Emissions

Neil Dixon, a professor of Civil Engineering at Loughborough University, has developed an alternative early warning system for landslides in accordance with eight requirements. Per Dixon’s stipulations, natural disaster warning systems should:

- Be low-cost

- Be easy to install

- Monitor spatial and temporal resolutions

- Operate within different site conditions

- Quantify slope deformation that poses a risk

- Be self-sustaining and require minimal human interaction

- Be networked to transfer information to users

- Be robust and have minimal false alerts

Dixon’s team has thus developed a system that determines landslide risk through acoustic emissions (AE), or the “generation of transient elastic waves produced by a sudden redistribution of stress in a material.” This means that an AE-based system, rather than measuring rainfall levels, gauges the level of disruption taking place within the soil below. This system, known as the Community Slope SAFE system, removes the need for government interference, democratizing alert systems currently limited to monitoring by geotechnical experts. Dixon and collaborators have developed a low-cost modification of this system for landslide-vulnerable areas in low and middle-income countries.

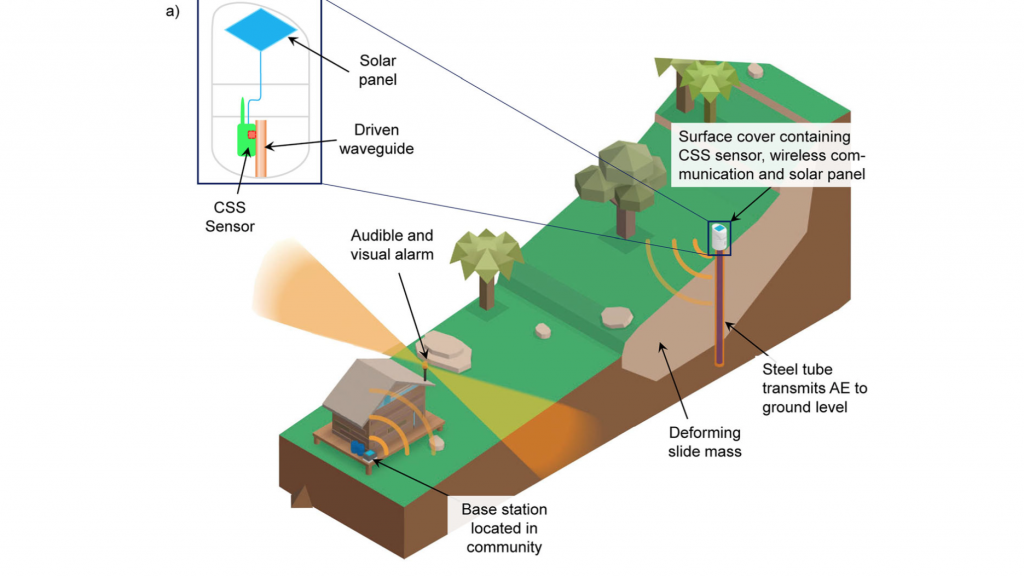

Simply put, acoustic emissions (AE) are elastic stress waves generated by the deformation of materials. In order to measure this stress, a steel waveguide is directly inserted deep into the ground and filled with “noisy” granular material such as sand, gravel, or crushed glass. Attached to the top of this waveguide is the AE sensor. In the event of significant slope movement, the material will shake rapidly inside the waveguide, generating AE waves up to the sensor, where the waves are converted to a voltage signal via what is called a piezoelectric transducer. Once a pre-determined threshold of movement is exceeded, an audio and visual alert is sounded to a base station placed in the community (which could be monitored by, rather than a governmental body, a favela community organization), which in turn warns residents nearby that rapid land movement is occurring and to begin executing plans of action, such as evacuation.

This direct line of communication between the base station and favela leadership is essential, as it reduces alert delays and removes the risk of inaction due to resident-government mistrust. Some favela residents tend not to leave their homes during times of crisis for fear of losing their homes and belongings, either to a natural disaster or to government intervention. Mariluce Mariá Souza, a resident of Complexo do Alemão, in Rio’s North Zone, says that some residents leave their house as fast as they can, but many are unable to do so. “Mostly, we just put the children and animals on high ground and pray and wait for [the rain] to pass,” she says.

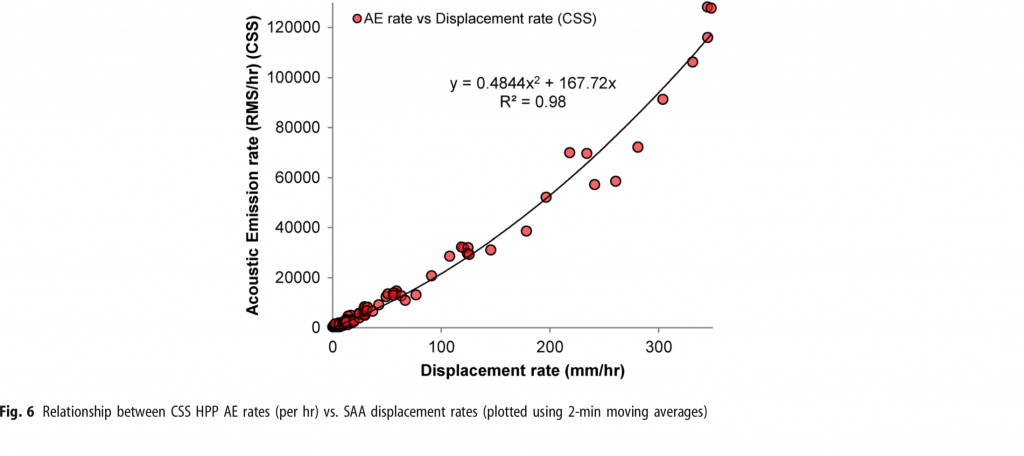

Several academic studies have confirmed that there is a direct correlation between acoustic emission waves and slope displacement rates, once a displacement rate has been established. In addition, the AE method comes at a comparably low cost. Based on research-related purchases, it was estimated that one sensor would cost the equivalent of a few hundred US dollars. Meanwhile, studies conducting comparisons between the CSS and other more expensive inclinometers have shown nearly identical detections. The flexibility of infill material (crushed glass, etc.) also provides viable reuse opportunities for bottles and other glass objects that would otherwise be thrown away. These systems can also use solar panels to power the AE sensors.

Furthermore, the system takes into account differences in land formation where landslides usually occur. AE soil movement thresholds can be easily adjusted by non-professionals according to specific aspects of the land susceptibility surrounding different communities. This community-level customization could cut down on false alarms and still catch critical events.

The AE early warning system—currently being tested in Canada, parts of England, and with a test site chosen for trials in Malaysia—seems a possible fit and much-needed upgrade for Rio’s favelas. AE provides a quicker, more viable, and lower-cost alternative to Rio’s current alarm system. Prioritizing favela community members as the first to hear about a potential disaster will help build trust between residents and the landslide warning system, whereas the current system as it is applied results in justified mistrust, false alarms, and questionable government intentions in evacuation tactics.

This article is part two of a series analyzing landslide and flooding mitigation tactics currently being utilized in Rio de Janeiro, along with descriptions of more community-based warning systems already being tested in other countries prone to natural disasters from heavy precipitation. Read part one here.