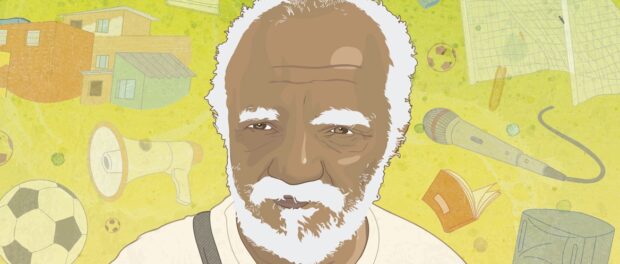

At age 64, Vanderley da Cunha, known as Deley de Acari, has been a poet, writer, human rights activist, and cultural mobilizer in the Acari favela, in the North Zone of Rio de Janeiro, for over four decades. He is founder of the Negrícia Creole poetry and art group, an activist in the Black Movement, and the 2008 recipient of the Chico Mendes Human Rights award from Grupo Tortura Nunca Mais (Torture Never Again). Since the 1970s, Deley has worked to combat human rights violations in the favela of Acari. Over the years, the community has suffered from the constant violence of Military Police clashes with drug traffickers. For over a decade, Deley has participated in the Network of Communities and Movements Against Violence, which brings together family members of victims of State violence. More recently, he participated in the creation of the Fala Akari Collective, a group of residents and activists of the Acari favela that aims to disseminate and promote cultural and educational actions and to denounce violations committed by the State in the area. As an activist who has always dedicated his heart and soul to the dignity of the residents of his favela, Deley had his importance to the community materialized in the Poet Deley de Acari Cultural Center (CCPD). When RioOnWatch surveyed a network of community organizers on the question of whom to highlight in a new interview, Deley was the name mentioned most, often by young leaders influenced by his legacy. According to Deley, this must be because of his “persistence and resistance.” Deley released his first book, Ainda Teremos Dublin? (Will We Still Have Dublin?), on August 5, 2019 in downtown Rio.

RioOnWatch: Where and when were you born?

Deley: I was born on October 7, 1954, in Londrina, the coffee capital, in the interior of [the state of] Paraná. I was raised in another municipality, Itambém, in the same city, until I was six. From six to sixteen I [moved and then] lived in Vila Norma, a favela in São João de Meriti [on the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro], where my grandma had a soccer team.

RioOnWatch: What was the most memorable event of your childhood?

Deley: The most significant event of my childhood was speaking on the community radio at my grandmother’s soccer club in São João de Meriti. I played records and broadcast messages to the residents. There was this eucalyptus trunk with four speakers sticking out of it, and it was through those that my voice carried information to everyone. When I began I was eight, and I worked there until my grandmother had a stroke and the soccer club closed. I was about nine years old then.

RioOnWatch: When did you go to Acari?

Deley: In 1974, when I was 20. At 16, we moved to Duque de Caxias, and then to Paciência. It was there that I started to participate in rock festivals, theater groups, and writing music lyrics.

RioOnWatch: When did poetry enter your life?

Deley: At age 16.

RioOnWatch: And how did your activism start?

Deley: My political activism started, and continues to be, in the area of culture, but before that, I had already had contact with Marxist literature, produced by my uncle who was an activist in a communist organization, at that time I must have been about 13. I started doing theater. I wrote a play with a friend in 1966, which was censored, and as a result, I was arrested for two days. It was a play about Juvenal, an old school master on the drums, along with other composers and some people from the dockers union, which at the time was the focal point of communist samba militancy. Juvenal was arrested and killed. We were rehearsing this play at the Armando Gonzaga Theater and the general director at the time reported us, unbeknownst to us, saying we were putting together a subversive play. We sent the piece in for censorship evaluation, and on October 6, 1976—when my friend and I went to find out the result at the Federal Police—we learned that the piece had been banned because it was in violation of all the stipulations of Article 41 of the [military regime’s] Censorship Code, among other things. On the way back, we were approached by a car and its occupants identified themselves as DOI-COD agents [a State intelligence organ under Brazil’s military dictatorship]. They wanted us to give a testimony about the play. I presented myself as the author, more the director than the author, so they let my friend go and they took me. I spent my 22nd birthday in jail. My mother, who worked in the home of Captain Pires Gonçalves, came to pick me up and I was released. If it hadn’t been for that, I would have spent more time locked up or even ended up amongst the disappeared. The lights were on all night and I must have been tortured for about 40 minutes or an hour.

RioOnWatch: And when did you start acting as an activist inside Rio’s prisons?

Deley: In 1987 there was an event at Talavera Bruce Women’s Prison, and I signed up to give text production workshops. This was a very remarkable thing for me. There were women of various nationalities, including Brazilians, who were arrested for transporting drugs. The workshops were held weekly with 25 inmates and lasted two months. At the end, they asked me to bring a pie. I bought two pies, one of each flavor, and eight bottles of soda. It was exciting, one of the prisoners said that she hadn’t eaten pineapple cake in 25 years—the whole time she had spent in prison. After that, there were readings, the Varal de Poesia [poetry clippings hung along clothing lines], and other things.

RioOnWatch: How do you describe yourself today?

Deley: I describe myself as a poet and cultural animator, most focused on popular education.

RioOnWatch: Your work with sports is very well known, how did you start?

Deley: Actually, I had always wanted to work in this area, as I was raised inside a soccer club where my grandmother was the matriarch. It was the most important club in Rio’s Baixada Fluminense region, with dances every weekend, festas juninas [June festivals celebrating St. John the Baptist], and the soccer team. I was also very influenced by my uncle who was a coach, but the issue of soccer was more out of necessity. In 1985, when I went to work at the CIEP [Zumbi dos Palmares] public school as a cultural animator, I set up a little indoor soccer school. In 1986 and 1987, I went to work with two physical education teachers and had the pleasure of putting things together, leading, and training. But earlier, I played handball, and we were student champions many times. That truly is my favorite sport.

RioOnWatch: How did your sports initiatives in Acari start, and in what year?

Deley: They started in 1993, 1994, when a sand field was built by a local resident. After this resident left, the field was idle, and we, Henrique and I, took over and organized the first school. From then on we have done various projects. The first was a project supported by the State Sports Office (SUDERJ) which was also responsible for running Maracanã stadium. Henrique and I started this project as volunteers, and we put together equipment with PET plastic bottles, for example, to replace the cones, and we used old tires as well. Then, the president of SUDERJ at the time provided the necessary equipment and materials. Then there were the projects supported by city government: Don Quixote, Mel (Sports and Leisure Movement), all soccer.

RioOnWatch: And the handball project?

Deley: I did handball on my own, and [the project] started because I didn’t have any activities for the girls, so I put together a handball project with almost 30 girls. And as it’s a sand-based sport, we played in Copacabana. This was in 1996, 1997. I put together a handball team with the girls, which was a big decision. This was able to take three of the girls to the Vasco da Gama team: Jéssica and Géssica, who were twins, and Elisângela. Vasco wanted the girls to play queimado [Brazilian dodgeball] because they had a lot of strength in their arms. So I took the twins at 15 and Elisângela at 16. The leaders were crazy and wanted to federate them, but they were only going to play championships the following year. They were federated and all of the documentation was ready. At the end of October, they told me to take them in January. When I went to find them to give the news, they told me they couldn’t play anymore because they were pregnant, all three at the same time. After this happened, I stopped. Handball was only then, but maybe I will start again.

RioOnWatch: From 1993 to the present day, how long have you participated in the sports community?

Deley: I haven’t stopped, so about 28 years.

RioOnWatch: How many young people do you think you have taught, trained, and supported?

Deley: About three thousand young people. Through the SUDERJ project, many boys went to practice athletics in Mangueira. Bruno, for example, was 14 and he was the runner-up in weightlifting. But Mangueira didn’t federate him, so I brought him to Vasco da Gama, where he began to train. He got shoes and the necessary equipment, but after he began to go alone, he took his travel money and did not attend training.

RioOnWatch: During all these years, have any of the young people you worked with turned professional or semi-professional?

Deley: Only starting in 2010. There are the boys who participated in the Favelas Cup: Marlon, who is at the América Futebol Club and Pedro, who is at Fluminense FC. There are four boys who are federated playing indoor soccer at Vasco. All are between 8 and 13 years old and there is a 14-year-old girl who is almost six feet tall.

RioOnWatch: How do youth interact with culture inside the community?

RioOnWatch: How do youth interact with culture inside the community?

Deley: I think it is interesting because two samba schools are led by former funkeiros. The story that youth culture doesn’t integrate with traditional culture is a biased, outsider view. The favela has always had something very dynamic. The young people that participate in carnival, the samba schools and Folia de Reis [a three kings celebration] are the same that participate in festas juninas. For example, the board of two samba schools that were founded, Favo de Acari in 2008 and de Acari, which is older, have boards formed by boys who started dancing funk and are from “Força do Rap,” the most famous funk band not only in Acari, but in all of Rio de Janeiro. It was the boys from the “Menores do Funk” group that brought the dance squads back and still dance to this day. And they are the ones who started to make festas juninas more dynamic.

RioOnWatch: Compared to other places, outside of the community, but inside Brazil and Rio de Janeiro, in what areas does Acari surpass those places?

Deley: It is the community ties, the families here are large, sometimes with 30 or 40 people. There is a family from Corinto that dances Folia de Reis and is made up of more than 300 people. The people [in this community] get attached.

RioOnWatch: And today, are young people having many children, are the families still large?

Deley: The families are still large, but not as big as they used to be. They have children earlier, but fewer. Today the majority of the population of Acari is female and young, because mortality among young men is much higher.

RioOnWatch: What percentage of the population is, directly and indirectly, involved with the drug trade?

Deley: Directly, less than 1%. Indirectly, an average of 20%. We have divergent figures. For us, the population of the Complexo de Acari is about 45,000 residents, but the City says that it is an average of 25,000. All of Acari must have an additional 160,000 people, including all of the favelas and the whole neighborhood in general. But in Acari, I believe that no more than 120 young people are involved in drug trafficking.

RioOnWatch: Has the number of young people that entered university risen?

Deley: It is not the ideal, but it has increased a lot, today it is around 60%, as the ENEM [college entrance exam] helps a lot, and most go to private universities.

RioOnWatch: In what situations does violence occur today in Acari?

Deley: Today, violence comes more from police raids than internally. The frequency of confrontations with police is now every week. The death of Maria Eduarda [at hands of police] happened in one of these confrontations in Morro da Pedreira which is inside the neighborhood of Acari.

RioOnWatch: How did her death affect the residents?

Deley: After such a tragedy there is always a compensatory project from the government, proposals from the City to shield schools and implement cultural activities. On the other hand, there is a negative effect because it creates the hope that after a tragedy things will get better. But this same government that prepares harm reduction and protection plans for young people and children, is the same one that puts the police on the streets the next day.

RioOnWatch: What was the result of the removal of residents of Acari to West Zone areas?

Deley: Many people returned because they were unable to pay the monthly fee. And the cost of living there is higher, and there is an issue of transportation expenses, which have tripled for some people.

RioOnWatch: Can you make a comparison of these two realities?

Deley: In Acari, the people who come from outside have no problem circulating within the community, while the [public housing] condominiums where they were moved are closed and guarded: they have guardhouses and people have to present identification to enter. They have no leisure areas or places for the children to mingle, so 20% of the people who were removed returned to Acari.

RioOnWatch: Can you compare this situation between Acari and the West Zone, where the people went to live?

Deley: I can talk about Acari’s experience. Relations are more flexible in Acari, traffickers are locals, everybody knows each other. Not the militia: it imposes itself in an authoritarian manner. Overall, Acari is still better, things are cheaper, and even the question of debt is more flexible. In Acari, the person that struggles with their rent, for example, can owe rent for two months, whereas those who live in the militia area can not. And there are costs that in the [Acari] favela do not exist, such as light bills and condominium fees.

RioOnWatch: Regarding the favelas, what do you expect for the future?

Deley: I think that if we who are from the favelas don’t believe that we are able to find alternatives for the community independent of government—but with help from outside alliances—it will get complicated.

RioOnWatch: If you had the resources to spend on public policy, what would you change in the current landscape?

Deley: I would generate jobs and income. For me, even if it’s done within the capitalist model, what is needed is to generate well-paid work, and that doesn’t happen overnight. One way of accomplishing this would be through public policy.

RioOnWatch: What is the unemployment rate in Acari today?

Deley: On average, 40%. But there are the unemployed and there are those without work, which are two different situations. There are few without work, because in one way or another everybody works. They do something for someone. The unemployed are those who simply gave up formal employment on the books.

RioOnWatch: Some time ago Acari was the favela with the lowest Human Development Index (HDI) figures in Rio, has this position changed?

Deley: The indices that IPEA uses are based on life expectancy, schooling, and formal work. Acari is likely among the bottom ten.

RioOnWatch: When did you start being called Deley de Acari?

Deley: It was about 1987. I was Vanderley da Cunha and so I joined the Composers Wing of the Quilombo Samba School in Acari. And there were three Vanderleys, so they decided that I would be Deley de Acari, but in the poetry world, I am Vanderley da Cunha.

RioOnWatch: What is your greatest legacy today, in the history of Rio?

Deley: I see little [legacy], I am not aware of all of this importance, no. But my poetry and the fact that I’ve been on this path for a long time, those can be legacies. But I don’t like being that sort of unanimity.

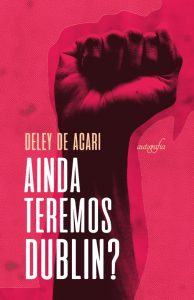

RioOnWatch: You’re releasing the book Ainda Teremos Dublin? (Will We Still Have Dublin?). Is this your first published book?

Deley: I’ve published poems in other books, but this is my first solo book. The difference is that this book is a collection of stories posted to Facebook after my return from Dublin in 2017 [from the Front Line Defenders meeting]. The intention of writing it was to have a more clear and less ephemeral view of the text posted on Facebook, which is very volatile.

RioOnWatch: What was the reason for the book’s title?

Deley: Shortly after Marielle’s execution, the risk to my life worsened and I doubted that I and other human rights defenders [from Rio] who had been there in Dublin would still be alive in 2019, when the next Front Line Defenders* event would take place. Hence the title.

RioOnWatch: To wrap up, is there anything else you would like to say?

Deley: I wish there was more unity. There is a lot of division for little reason. I would also like people to know that with the book sales I am able to maintain the soccer school in Acari.

Deley de Acari held a book signing night for Ainda Teremos Dublin? on August 5. At the launch, there was a poetry and conversation circle.

Deley de Acari held a book signing night for Ainda Teremos Dublin? on August 5. At the launch, there was a poetry and conversation circle.

Deley “makes an anthropology of pain and struggle in this book by highlighting the anonymous trajectories of residents of the Acari favela located in the North Zone of Rio de Janeiro. Thus, it uniquely combines narratives and poetry—its production is ample—and here we have only a small but expressive part of it—the trajectory of public personalities such as Councilwoman Marielle Franco herself, brutally murdered in March 2018, as well as black women persecuted, harassed, and silenced in favelas in Brazil, especially those who lived most of their lives in the favela.”

*Front Line Defenders was founded in Dublin in 2001 with the specific objective of protecting at-risk human rights defenders (HRD) who work non-violently for any or all of the rights set forth in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR).