In celebration of the 50th anniversary of New Communities Inc., the world’s first Community Land Trust, and as planners and community members alike gather to celebrate October 2-5 at the Reclaiming Vacant Properties Conference 2019 in Atlanta, Georgia, RioOnWatch issued a call for articles highlighting the current growth of the CLT movement worldwide. Contributors wrote in from around the world, with stories about the expansion of CLTs—both in number and in approach—in Mississippi, the United Kingdom, Belgium, France, Puerto Rico, Rio de Janeiro, and Florida. This varied series aims to disseminate news of the successes of the CLT model as it adapts to new times and circumstances, bringing greater attention to this innovative solution to guarantee the right to housing and community development, and its potential in resolving the global housing crisis.

Today’s piece, by Sciences Po Master’s Candidate and Catalytic Communities intern Tara Nelson, digs into the burgeoning rural and urban CLT movement sweeping across the United Kingdom.

For more information on CLTs and their potential for Rio de Janeiro’s favelas click here for text and here for video.

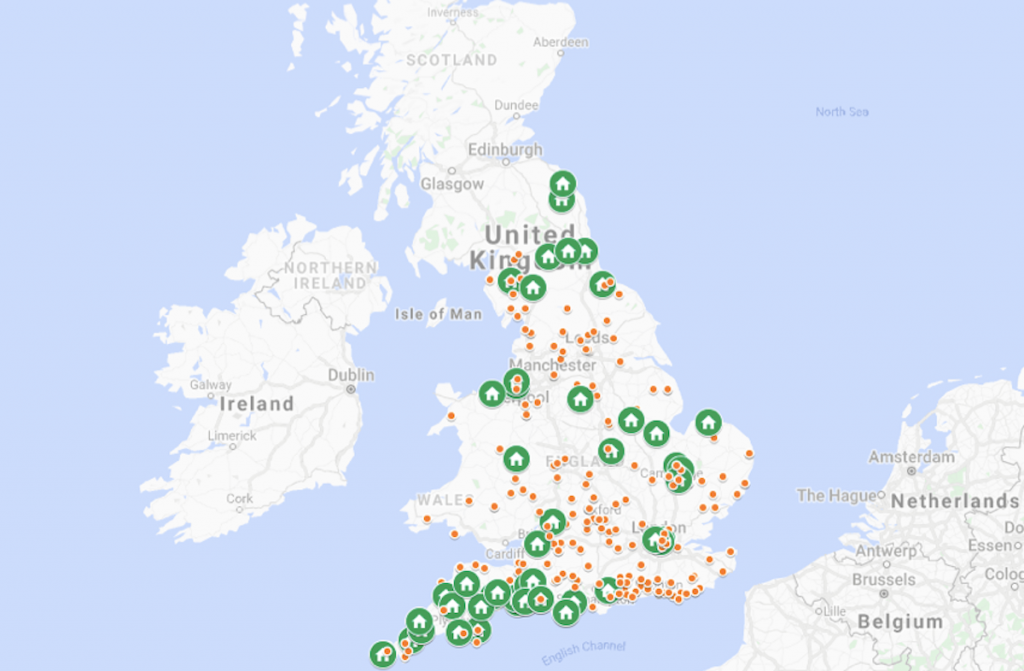

Over the last decade, the number of Community Land Trusts (CLTs) across England and Wales has increased from 14 to over 300, containing 935 CLT homes with another 5,000 in progress. In the face of an acute national housing crisis, CLTs offer a promising solution to those hard-hit by the reduction of social rent and social housing and high private rental costs.

Under the UK government’s ‘Right to Buy’ scheme, social housing has been sold off at a startling rate. 40% of what was originally built as social housing later bought under the scheme is now rented privately, with some town councils being forced to buy back properties sold through the scheme at six times the amount they were sold for. Although the scheme has helped many families get on the property ladder, for others, the private sale and rent of homes built for the public good is having devastating effects on the availability of social housing for those most in need.

In May 2019, the National CLT Network, a charity founded in 2010 dedicated to supporting CLTs in England in Wales, held a transnational CLT conference at London City Hall. Bringing together delegates from across Europe to discuss CLTs and “a new kind of municipalism,” policy-makers from London and Europe signed an open letter calling for support for CLTs across Northwest Europe. The conference represents just one of the many advancements that the UK CLT movement has seen recently, highlighting a booming interest in the movement across the UK and Europe.

CLTs in the United Kingdom

Inspired by the CLT movement in the United States, the first UK CLT was created in 1983. That CLT, the Stonesfield Community Trust, developed in an effort to ensure village viability and affordable homes amid steep increases in land value in the area of West Oxfordshire at the time. Over the following three decades the movement grew, taking off from 2006 through 2008 with a National CLT Demonstration Program, led by Community Finance Solutions at the University of Salford, which supported a number of pilot projects.

With support from both Labour and Conservative parties at the time, a statutory definition of CLTs was added to the 2008 Housing and Regeneration Act, marking a victory for the movement across the UK. While far from providing a comprehensive definition, the text gave the movement legitimacy, aligning it with the objectives of local authorities. The subsequent establishment of the National CLT Network in 2010 provided additional momentum, assisting both existing and prospective CLTs.

Rural and Urban

With a history primarily in the countryside, rural CLTs can be seen as the classic case for CLT development in the UK. In Scotland, the movement began in the 1990s, with Scottish crofters using CLT models for community buy-outs from absentee aristocratic landlords. Across England, they have developed in communities with dwindling services or where the effects of high levels of second home ownership are particularly acute. The expansion of the rural CLT movement in recent years highlights the diverse ways in which CLTs can be applied beyond the provision of affordable housing. The Wyre CLT, for example, has worked in Worcestershire’s Wyre Forest since 2007, nurturing the farmland and woodland in the area, helping local people make a living from the land. Formed in April of this year, the Middle Marches CLT is committed to protecting, conserving, restoring and enhancing land in the Shropshire Hills nature reserve.

In the UK’s cities, CLTs have grown in a context of—and in response to—pro-market and neoliberal urban development, which has rendered the housing market inaccessible to many. While in the UK the urban movement has traditionally expanded more slowly than its rural counterpart, new sources of funding have changed this. The National CLT Network implemented an Urban CLT project in 2014, providing 19 urban CLTs across the country each with a £10,000 grant. In early 2019, London Mayor Sadiq Khan announced a £38 million fund for the development of community-led housing, in an effort to demonstrate the city’s commitment to reaching targets of implementing 1,000 community-led housing schemes in the capital by 2021. Speaking to the Mayor’s office, Linda Wallace, Chief Executive of CDS Co-operatives called the fund “the most significant investment in community-led housing in a generation.”

In the nation’s capital, the London CLT has made major strides. Originally known as East London CLT, one of Britain’s first urban CLTs, the London CLT developed in a context of gentrification and failed regeneration schemes, as a rapid rise in land and property prices stoked inequality, creating pockets of poverty across the capital. In just under two years, 23 CLT homes have been occupied at the organization’s pilot site, St Clements in Mile End. With house prices pegged in relation to local income, St Clements represents some of the only truly affordable housing in London, with properties sold for around one-third the cost of market housing in the same area. Earlier this year, the London CLT received planning permission to build eleven homes at a site in Lewisham, South London. With projects at similar stages in Shadwell and Lambeth (in East and South London, respectively) on sites won from Transport for London, Greater London’s public transportation body, the London CLT could see its largest builds yet, with the potential for 35-40 homes in Shadwell and around 20-30 in Lambeth. In a city where, in most areas, not one of the single rooms available for rent falls within the budget of those on housing benefits, the London CLT presents the seed to a promising alternative.

Outside the capital, urban CLTs are making their impact. In Liverpool, the Turner Prize-winning Granby 4 Streets CLT has seen progress in an area affected by failed regeneration schemes and years of economic deprivation. Aside from the provision of eleven homes, bought from the council for just £1 each and transformed into affordable homes both to rent and buy, the CLT also runs a popular community street market and is in the process of building a community meeting space. There are future plans to take on a small business advisor. Similar projects are in place in other cities affected by high levels of gentrification, such as the coastal cities of Brighton and Bristol.

New Partners and the Long Road Ahead

With increasing recognition of the role community-led housing can play in tackling the nation’s housing crisis, support from local authorities as well as the central government is growing. According to the National CLT Network, more councils than ever before back community-led housing development. One in six councils has policies to support community-led housing and one in three have given grants or loans for community-led housing. In London, Croydon Council recently released a site for community-led development which has received bids from both London CLT in partnership with Croydon Citizens, as well as the newly formed Crystal Palace CLT.

From the central government, the Community Housing Fund promises £163 million across England for community-led housing. Running from 2018 to 2020, the fund aims to increase the number of homes delivered by the community-led housing sector. It is expected to deliver 10,000 homes by 2021, many of which could be delivered by CLTs. However, the bidding process was delayed, and organizations only have until the end of 2019 to submit their bid, leaving just a few months to apply. The National CLT Network is currently campaigning to extend the deadline beyond 2019/20. Speaking to the BBC, Tom Chance, Director of the National CLT Network commented, “So we’re really now entering a period where communities across the country are trying to do these projects. They’re saying to the government ‘we want to be part of the solution’ and the government is turning them away potentially because they can’t fund them beyond 2020.” Such a fund could be transformative for the CLT movement. Without a deadline extension, however, many potential CLT projects could go unrealized.

Despite its many successes, the movement faces a long road ahead. “I think the biggest challenge is how does it [the CLT movement] balance its desire for democracy and grassroots activism with the degree of professionalism on a scale that can deliver,” says Dave Smith, former Director of the London CLT. As CLTs such as the London CLT grow from one-site organizations to a multi-site, pan-London organization, the question of professionalism—and of ensuring that decision-making is still devolved across all actors—is of huge importance. Access to financing also remains an issue for many CLTs, especially in regard to mortgages for users. CLTs are still a relatively new concept, and remain unknown to many larger mortgage lenders. Though some CLTs, such as the London CLT, have received support from banks and building societies, more campaigning is needed to increase visibility and bring new partners on board.

And so the movement continues to push on, benefiting communities with much more than just affordable housing: residents continue to benefit from CLTs long after moving in. “I feel like a big part of what we do is building people’s skills and capacity to campaign in general, and people’s political power,” says Lianna Etkind, Campaigns Manager at London CLT. CLTs continue to empower communities failed by more than a decade of austerity and a broken housing market. Speaking at the 2012 Liverpool Biennial and in conjunction with Homebaked CLT, artist Jeanne van Heeswijk said, “Housing is the battlefield of our time and the house its monument.” The sentiment resonates with many, and will continue to ring true as communities find new ways to take control of how and where they live.

This is the second article in our series on the growth of the global CLT movement. Click here for more.