This is the second article in a year-long partnership with the Behner Stiefel Center for Brazilian Studies at San Diego State University to produce a series of monthly favela-sourced human rights reporting from Rio de Janeiro on RioOnWatch. The following interview was conducted by Carla Souza, an early childhood education professional raised in the favela of Rocinha, as a special contribution to RioOnWatch.

This is the second article in a year-long partnership with the Behner Stiefel Center for Brazilian Studies at San Diego State University to produce a series of monthly favela-sourced human rights reporting from Rio de Janeiro on RioOnWatch. The following interview was conducted by Carla Souza, an early childhood education professional raised in the favela of Rocinha, as a special contribution to RioOnWatch.

Exactly one year ago, around 7:30am on September 18, 2018, residents of the Chapéu Mangueira and Babilônia favelas, in Rio de Janeiro’s South Zone, marched in spontaneous protest, carrying with them the umbrella that Rodrigo Alexandre da Silva Serrano, age 26, had been carrying when Rio Military Police allegedly mistook it for a gun. According to residents, on the previous evening, when Serrano was standing at a bus stop in Chapéu Mangueira—waiting for his wife, wearing a baby carrier to place their small child in, and holding an umbrella—police climbed the hillside firing when they confused Serrano’s umbrella for a gun.

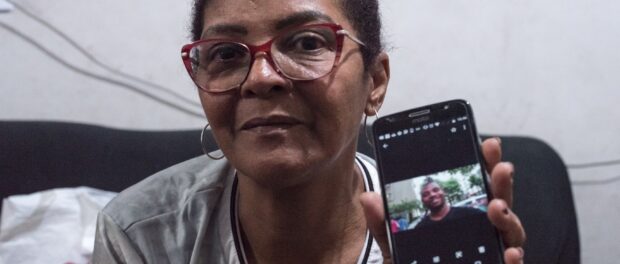

A year has gone by and RioOnWatch listened to Valéria Assis da Silva, Rodrigo’s mother, who shared with us this touching interview documenting Rodrigo’s story and the pain of those left behind, while still having to fight for justice, becoming yet another of the countless mothers of victims of State violence in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro.

Dona Valéria is a black woman and resident of Rio’s West Zone, mother of three—two boys and a girl she adopted at age 12, now age 32—and grandmother of seven. As is common among black women in Brazil, Valéria divided her time between providing for her home and taking dignified care of her children. And that is how it went! Rodrigo, one of Valéria’s children, born and raised in the Cesarão public housing complex in the West Zone neighborhood of Santa Cruz, took to soccer early on, playing in neighborhood games and at local soccer clubs—his family looks back fondly on his sports career to this day. They proudly remember his smile and camaraderie: he was good people. Many old photos show Rodrigo’s wide grin, as his sister-in-law described during the interview, “it looked like he had 300 teeth in his mouth.” While his mother spoke wistfully of Rodrigo’s soccer career, showing off the stamps in his passport of international trips taken, and other photos of Rodrigo with his wife and children at the beach and at parties, Dona Valéria became discreetly emotional and thought out loud: “what a handsome boy!”

He was her boy. He was father to Ravi and to Ryan. Husband to Thayssa. Brother of Leandro and Maria. But to the police, he was a black man in the favela at night. To the press, he was the young man who died for holding an umbrella in his hand, and this object—through the lens of structural racism—appeared to be a gun. He was the man who had his worker’s ID card stained in blood, whose death was displayed on national TV as another case of an alleged shootout that never happened, a non-existent confrontation in a fallacy-ridden War on Drugs.

Since the colonial era, black Brazilians have had their identities made invisible as part of a process of dehumanization. In this interview, however, Dona Valéria, mother of Rodrigo, will recount and repeat his name. His story will be told honorably.

RioOnWatch: How would you describe Rodrigo’s childhood?

Silva: Rodrigo had a normal childhood, just like any other kid. He was healthy, playful with his friends. He loved to play ball, he and his brother. He started playing soccer at nearly seven years old with a neighborhood soccer club. Then he joined the local Vasco sports club soccer group, and from that point on he took off.

He was a great son, he knew how to do everything. When he was seven, Rodrigo had already learned how to cook, bake cakes, take care of the house because I had to work and I had separated from their father when they [my children] were young. He was the youngest, but sometimes he would seem like the oldest. He took on responsibilities at home, helping his brother. The two of them had to take care of things at home for me to work. I couldn’t afford to pay anyone to take care of them. And they took care of everything for themselves at home. I would come home and find everything ready and done. After I separated [from their father] it was just me and them. I had to fight. I had to really go after it [to sustain the family].

He stayed living here [in Santa Cruz] until 2012. He didn’t go straight there [to Chapéu Mangueira]. He got together with Thayssa and lived with her first in Realengo. They were renters and it was then that he went off the rails and got arrested. He spent three years in jail. He got out when it was time, with everything okay, on parole. And that was when he went to live with Thayssa [in Babilônia] at her house.

Silva showed us photos of Rodrigo with the Corinthians soccer team in São Paulo. Rodrigo spent a number of months in Norway, as a striker. He played for the Vasco, Botafogo, and Fluminense teams. According to his mother, he stopped playing because of his girlfriend. He thought he wouldn’t make it as a professional player and didn’t want to depend on his mother any longer.

RioOnWatch: How was your relationship once Rodrigo moved to Babilônia?

Silva: Everyone knows me there [in Babilônia]. Some come out and hug me, because sometimes they catch me, as I walk down the hill, crying on my way out… [Silva pauses, begins to cry]. I try to go there and not get emotional, for the boys, because Ravi [Rodrigo’s oldest son, age five] lived through all of it, you know? It’s all still with him. He says that his dad got shot [Ravi saw his father moments after he was shot]. I go there, strong, and I play and laugh, but when I leave it’s like I’m going through it all over again.

RioOnWatch: How did it all happen?

Silva: It was at the front, near Bar do Davi, a famous local bar. I was always there on one weekend or another, making up for the time he spent far away from me. At the end of last year, it was going to mark three years since he’d come out of the [prison] system. He was working, doing well, and he was happy, really happy. As soon as he got out, he got a few jobs, though they were informal. You know how it is for people coming out of prison. [When he was killed, he was in] his first formal job [with full worker’s rights]. He was really excited about his baby’s first birthday, because he had been out of prison and had been there for the whole pregnancy. He was always talking about it. After everything happened [Rodrigo’s death], if you went to [where he worked], his boss started talking, telling all about how everyone liked him, including his customers.

Rodrigo’s son’s birthday party was held in November, two months after his death, in commitment to realizing his wish.

RioOnWatch: How did you hear the news?

Silva: When I got the news, I wasn’t living here [in Cesarão]. I was living in downtown Santa Cruz. Thayssa called me saying that he had been hit. It was night when she called. I got anxious, pulling all my things together quickly and praying to God: ‘Take care of my boy… nothing is going to happen to my boy… watch my son, keep him from dying. Wait for me, I’m coming…’ I was already in the car, going as fast as I could to get to the hospital, and Thayssa said to me: ‘Don’t rush, because you could have an accident and be another statistic, and [besides] there is nothing left to be done.’ So I controlled myself, for him [Leandro, Rodrigo’s brother], because the friendship between the two was so great, they were always together [and Leandro and his daughter were in the car]. I controlled myself and got there [to the hospital], singing happy birthday to entertain the baby. And holding back my tears to not show my emotion. At the hospital doors, I told him: ‘My son, your brother is no longer with us.’ [Silva cries.]

We met with Thayssa, and, talking to her, she said that the doctor told her that Rodrigo had arrived having been shot three times, and that she had asked for the baby carrier sling he had had with him. It was what the police were alleging, that he had a gun, which was the umbrella, and a bullet-proof vest, would have been my grandson’s sling baby carrier. I spent more than half an hour looking for it at the [Miguel Couto] hospital but had no success. I couldn’t find the “bullet-proof vest.” I haven’t found the sling to this day…

RioOnWatch: He was on his way to meet Thayssa?

Silva: No. He went to work, left work, asked for a R$50 (US$12) advance from his boss and went there [to Chapéu Mangueira]. He met Thayssa at home, got the kids, and they went [down the hill] to pick up [her] Bolsa-Família [welfare] allowance. Then they went to the supermarket, to the lottery [where bills are paid], and to the fruit stand. They were starting back up the hill to their home by foot, but it started to drizzle. He went back down with her [to protect her and the children from the rain], put them in a kombi [VW van used as informal community public transport]. He set the shopping bags [in the van] and took with him only the umbrella and the little bag of fruits, and started off out front. He took the baby out of the carrier and took the carrier with him, the bag, and his hat. Then he set off by foot. Since he’s an athlete, he got there before the van did [the kombi will often wait to fill with passengers before departing]. Since he got there first, he stood waiting between the trash dumpster and a taxi, smoking his cigarette and holding onto his umbrella. There was no police operation that day. Thayssa heard the shots and said: ‘My husband! My husband! He is there waiting for me…’

Witnesses told Silva that, even after being shot, Rodrigo was worried about his wife and children on their way up the hill.

RioOnWatch: What do you hope will happen with regard to Rodrigo’s case?

Silva: I looked into it and there is still no investigation into the Military Police officers involved. I would like them to speed up the process and give this more attention, because as time goes on, things start to be forgotten. For them. For me, no! I would like them to show me more care in relation to this. I want them to go to court to prove they made a mistake. No formal complaint has yet been filed. The complaint was made by me and Thayssa. We took it to the Public Prosecutor’s office, and the case went the Homicide Division in [the neighborhood of] Barra, but so far we have no answers. It has been a year and there have been no conclusions. I want to continue to fight and prove that my son is innocent, and I want to help other mothers to not lose hope.

RioOnWatch: And do you want to join the groups of mothers that have had their children killed by the State? If yes, what is it that you want to ‘yell’?

Silva: Yes, I want to join this fight. I want to try to say—though our Rio is getting worse and worse—that I want to make sure that there are no more Rodrigos, no more Amarildos. We need to try at least. We cannot let things happen the way they do, with them tearing our children from us so brutally. You can’t just stay quiet with things like this happening, and there have been others besides Rodrigo. There is him [pointing to Rodrigo’s brother], my grandsons and granddaughters. We’re at the mercy of this violence, of this neglect. I want to honor my son’s name. He messed up; he paid his dues. But when he died, he hadn’t done anything wrong. I don’t want him to go down as a criminal, or as a former prisoner. Talking about Rodrigo just because he spent three years in prison is easy, but what about the rest of his life? He played soccer, he traveled and lived in another country… He played for Corinthians.

RioOnWatch: What is your opinion on the way the police act in the favelas and peripheries?

Silva: What happened in City of God [last week] was horrible. The caveirão [police armored personnel carrier] going in and knocking down people’s houses. People say to me ‘But there are criminals there!’ Even if there are, every place has criminals! You can’t do that to people’s houses. There could be children in there. In the favelas, there are a lot of good people, people that wake up early to go to work and to honor their families. I remember the drill case, the boy that had the [hydraulic] jack, and the case of the boy in Deodoro [in which the military shot 80 times into the car of Evaldo Rosa, killing him]. When we see this kind of thing on TV we get shocked and think that it could never happen to us. Even today I am still afraid for my grandkids. I think the government needs more experience to deal with this, because it seems like they don’t know how to deal with it, how to address it. Our governor said that [police] need to arrive shooting. How can you arrive already shooting? There are residents and children there, you can’t just start shooting. You have to make arrests and put people in jail, but not just put people in jail. Prepare them for jobs, offer educational courses. Pay your sentence with work, work at a factory. All there is today is killing and killing for any reason whatsoever.