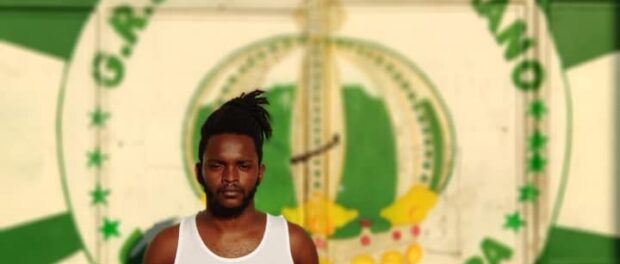

My name is Flávio da Silva França Alves, better known as Mestre Flavinho. I am a batuque and jongo percussionist, member of the Império Serrano samba school, and founder of Projeto Herdeiros (the Heirs Project). Born and raised in the favela of Morro da Serrinha, since the first hours of my life I have received visions of my ancestral origins from Olorun.

The History of Morro da Serrinha

The community of Morro da Serrinha has existed for more than 100 years. It is situated in Madureira, in the North Zone of Rio de Janeiro. Its story starts soon after the beginning of the 20th century. After the abolition of slavery by law and the proclamation of the Republic in Brazil, people who had been enslaved didn’t receive any kind of compensation. The jobs they were doing in the fields under slavery were replaced with the labor of European immigrants who, unlike those who had been enslaved, earned money for their work. The lack of prospects in the country forced a black migration to the then capital, Rio de Janeiro.

At that time, the downtown Centro area of the city seethed with people from different races and classes, something that didn’t please the bourgeoisie. In response, then-Mayor Pereira Passos put into practice the famous Bota-Abaixo upgrading reforms, demolishing the tenement buildings in the area to construct what is now Rio Branco Avenue.

Why go so far back? Because to understand Serrinha, we must connect with our past. The first residents of Serrinha came from those same plantations in the Paraíba Valley region and Rio’s Centro following the Bota-Abaixo demolitions. Each brought their own knowledge with them; some brought a plethora.

My Story in Serrinha

When I was younger, I was always really fascinated by the conversations and questions that the community’s elders shared with us, the information they brought us from the time of slavery in Brazil. My granddad, Guaracy Rosa, a dock worker by profession, originally from the Congo, was a batuque and jongo percussionist. He brought with him the teachings of his father, and from there, passed on to me what he had learned. He would often say that “everything was a mystery and that children couldn’t get very involved in those things.” That’s where my questions come from, because it was always like that: maintaining the tradition of the jeitinho that my granddad taught, everything came down to a coffee and a good old chat.

When I would take hold of my mother’s pots and pans, from an early age I was already drumming on them. The old man would say to me: “You do it like that? Patum patum papa tacaticatá,” honoring the oral culture and the continuity of samba. It was in this way that I learned and passed on our musicality to my children.

As children, we would create a new game every day, from games of tag to setting up drums out of old cans and buckets and pretending to be the mestre sala and porta bandeira samba school dance partners. Our favela has a contagious rhythm.

From the 1990s, funk carioca—also of African rhythmic origin—took over our imaginations and our house, making everybody shake their behinds and twist and turn their bodies. My mother danced to funk while she washed the dishes. I, all active and quite grown up in the 2000s, got together with the crew from my generation and created a group of funk dancers, the Bonde dos Neguinhos. It was a historic and impactful moment in our lives.

Serrinha as a Great History Lesson

Jongo and Samba came to Serrinha as a result of public policies of exclusion. We regard jongo as the father of samba. There are those who say that it is the grandfather. It is the rhythm of an African ethnic group that was trafficked from their homeland to do slave work in Brazil, and who survived through all the suffering on the plantations. On the sugarcane and coffee plantations, black people used the jongo songs, called pontos, to communicate. When they used metaphors, they could only be understood by jongo players.

Samba was born after the abolition of slavery, with a strong political bias—and it is like that even today. During the period of segregation policies, Afro-Brazilians couldn’t take part in the great carnival party and so they created their own party, which was founded on samba. It was not only a party, but an act of resistance. At the beginning of the 20th century, samba was a marginalized and criminalized rhythm due to these African origins. In fact, all kinds of cultural expression of African origin have been marginalized throughout history—yesterday’s samba is today’s funk.

Like with samba, religious practices of African origin were also criminalized. Serrinha wouldn’t have its musical origins without the terreiro practitioners who put up their tents in the community. There were days and nights where sound met, in which Umbanda and Candomblé terreiros would light their melodious bonfires in harmony with the land.

All this turned Serrinha into a factory of local culture. Walking in Serrinha today is like a history lesson. Going through its streets and alleys, we see the presence of the artists of Serrinha who lived here. Entering through Composer Silas de Oliveira Street (the poet behind Aquarela Brasileira), we arrive at the House of Jongo, which in turn is next to the Vó Maria Joana daycare center, named for a great jongo matriarch. A bit above, we go down Mestre Darcy do Jongo Street, and ahead to the left is the famous Balaiada Street—which is now called Tia Eulália Street. That was how Tia Ciata and Tia Eulália organized the famous pagodes with samba and jongo players. And it was in her house that the Império Serrano samba school was born. Let’s not forget the late Mano Décio da Viola, after whom the street parallel to Composer Silas de Oliveira street is named—both got together with Manoel de Ferreira to compose the anthem “Heróis da Liberdade” (Heroes of Freedom) for Império Serrano’s 1969 carnival parade.

Serrinha today

All this history and culture strengthens current local actions. A living example of this is the Casa do Jongo da Serrinha (Serrinha’s House of Jongo), which accepts local children for dance, music and popular culture classes, in addition to housing Projeto Herdeiros (Heirs Project), of which I am the founder. The project unites young people in musical instrument classes, giving continuity to the samba legacy that has been present since the foundation of the community. In this way, we facilitate the training of future percussionists in our Samba Symphony. The documentary film Herdeiros (Heirs), which is nearly finished, portrays this attempt to occupy the space and appropriate narratives to launch a new perspective on the local culture and recover forgotten names in the history of music, as well as empowering future generations in an effort to create a sustainable system.

Other good examples of local cultural actions are Samba in Serrinha, a traditional semi-acoustic samba roda that also takes place at the House of Jongo and brings the community closer to its musical roots; the Império do Futuro, the first carnival school for children in Rio, created by Mestre Careca (a Mestre who is a whole samba school all by himself and also trained the founders of the Heirs Project in music); and the web show “Fala Serrinha!” (“Have your say Serrinha!”), created and directed by the magnificent João da Serrinha, which transforms every resident into the protagonist of their own story.

The Struggles Never End

“Our favela has more night than day,” said the great poet, griot, and jongo percussionist Celso Marinho. The phrase reflects a tough reality—these days there is such oppression that we need to be alert and strong all the time.

The Jongo da Serrinha group had always dreamt of having a physical space inside the territory where it was born. Our matriarch Tia Maria do Jongo made it happen. A few years ago, she went to the office of then-mayor of the city of Rio de Janeiro, Eduardo Paes, and made the request—though many say it was actually an order. Even today, the House of Jongo stays open to receive and shelter all those who are struggling and sweating with no help from the government. We are supported by networks of friends who keep us on our feet and by an online donations page that provides financial support for the maintenance of the House of Jongo. There are many arms and legs undertaking a great journey together.

The Heirs Project, in turn, is fully maintained by volunteers. In order to strengthen the teachings of our ancestors, which were passed to us by word of mouth, and attract the youngest residents to these traditions, we offer classes in popular Brazilian rhythms, strengthening their self-esteem and giving them new perspectives for a better future. Projects like this one and the others that take place at the House of Jongo are of fundamental importance for strengthening Brazilian culture and its historical and social understanding, as well as for the professional training of young people.

While residents fight to maintain the memory of jongo and samba in Serrinha, politicians turn a blind eye to serious problems, from basic sanitation to the right to come and go. Community residents have always suffered from the insecurity of insufficient public services being offered, from unemployment and from negligence in the maintenance of schools. The insecurity of health services and the water supply makes survival even more difficult in the community.

The Arrival of Coronavirus and a Request for Help

With the lack of opportunities and restricted access to those opportunities that do exist, a large number of the residents of Serrinha undertake informal work: helping with construction work, collecting cans, recycling materials, and selling food on the street, among other odd jobs. They have gotten by as they could, but it has never been enough. The arrival of coronavirus has made this situation even worse. If before there was little left over to go around, now there is nothing. The number of informal workers has multiplied with the rise in unemployment, increasing competition for scarce opportunities. The current “misgovernment” has no empathy and provokes hopelessness among the population.

Faced with this situation, the true quilombo of Serrinha stays united, trying to help each other and asking the orixás for strength, with faith and certainty that this storm will not knock us down. And just as they were for our ancestors, the jongo songs have become an act of resistance…

…and stop killing us!

Asé.

How to Help

Serrinha, like many other communities, needs support. The residents’ association is receiving food, water, and financial donations. Get in contact by email: mestreflavinho@gmail.com.

The campaign Avante Serrinha (Forward Serrinha), run by Companhia de Aruanda, an artistic and cultural collective for Serrinha and its neighbors, is collecting food, cleaning supplies, and personal hygiene products for the residents of Morro da Serrinha. Donate here!