This is our latest article on Covid-19 and its impacts on the favelas. For the original article published in Portuguese by Rafael Galdo in O Globo, click here.

In Complexo do Alemão, with more than 70,000 residents, official statistics only counted 12 coronavirus infections and 5 deaths by July 3.

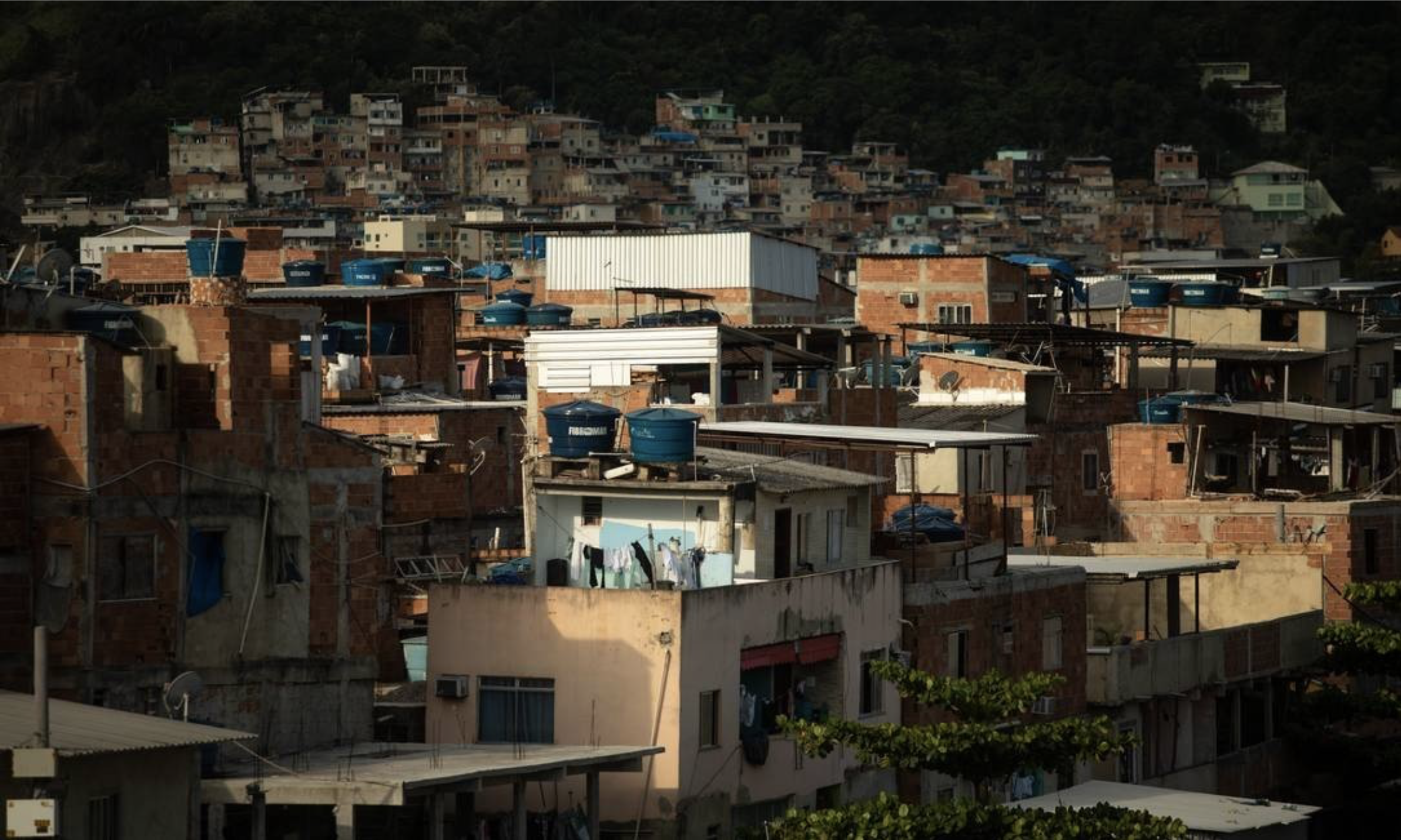

Amidst the pandemic, Rio de Janeiro’s favelas watch coronavirus spread while the victims of this disease remain almost invisible to the epidemiological system. Experts and favela leaders are faced with data that, while only lightly analyzed, already suggest there is something wrong—or still hidden—about Covid-19’s route through these territories at the margins of healthcare services, where a tragedy is feared. While the city has an average case fatality rate of 11%—even lower in Rio’s [upscale] South Zone neighborhoods,—deaths surpassed 20% of confirmed cases in Maré, Rocinha, City of God, Acari and Vila Kennedy favelas. It is a signal that many infected people were never identified by the health system.

In addition to the underreporting in diagnosis, the low number of deaths in Alemão, in relation to the rest of the city, has not yet been explained. With more than 70,000 residents, one of the biggest favela complexes in the city had, according to official statistics, 12 infections and 5 deaths due to coronavirus.

The obscure reality worries many people and leaves doubts about the future impact of the virus in a possible “second wave of infection,” especially with the end to the quarantine.

“These numbers cannot be trusted, which is a problem when it comes to flexing quarantine requirements. In poor areas, where most people rely on the public health system for testing, underreporting is higher. Basically, only people hospitalized with grave cases are diagnosed,” says Alberto Chebabo, an infectologist at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), explaining that the lack of tests influences high case fatality rates (deaths as a proportion of confirmed cases) in the favelas. “The deaths were registered, but without the cases being identified, the statistic is altered.”

In Maré alone, 27 people died between April and May in their own houses. The “hidden pandemic” in the favelas was the subject of research conducted by the city government and Ibope (a research and polling institute). After only one round of testing was carried out in four places—Rocinha, City of God, Maré and Rio das Pedras—it was possible to project that there were 90,200 infected people who never appeared in the counts by the city or state health departments. But, doing the calculations, the first three favelas only had, until July 3, 857 confirmed cases and 186 deaths.

“One cannot trust these figures, which is a problem when it comes to flexing quarantine requirements.” — Alberto Chebabo, UFRJ infectologist

Accounts from residents and NGOs—who took the front line of action against the virus in the absence of public policies—help to tell the real story of the coronavirus in these regions. In Alemão, the Covid-19 in Favelas Unified Dashboard* already displays a discrepancy between what the government says and what has in fact happened. Instead of twelve cases and five deaths, there are 108 diagnosed cases and 37 deaths. Rio das Pedras—one of the large West Zone favelas, with a hectic routine of 140,000 residents and 3,700 entrepreneurs—has another reason for appearing little in the statistics. Its residents who got sick were counted as if they were from [the broader areas of] Itanhangá, Jacarepaguá or even Barra da Tijuca. The city government calculates that 25% of the population there has already been infected by coronavirus. More is not known.

Fear of Stigma

With the avalanche of small business closures and legions of workers who lost their jobs, many of them waiters, cooks and housekeepers, the NGO SocialBit in Rio das Pedras, previously focused on technology, began distributing basic foodstuffs. Érika Alves says that the organization tried to set up a dashboard of their own, but it faced more resistance than it predicted.

“Many families are ashamed of saying there is somebody sick at home. They simply isolate themselves, maybe in fear of being stigmatized,” she says, affirming that there is a denial of the disease, which makes accounts of pneumonia and heart conditions increase.

The lack of testing makes it so that many people are never aware of whether they had the coronavirus. Manicurist Marília Paixão, 57, felt ill for 25 days, with shortness of breath and loss of taste. Even after seeking out the health system four times, she was not tested. Among friends alone, by her count, twenty people have died.

“I’ve had many losses, I couldn’t work for months, and I still live with the uncertainty of whether I had this disease,” she says.

In Maré—where officially there are 357 Covid-19 cases and 80 deaths—, the bulletin “Eye on Corona!” by Redes da Maré better translates the daily life of its 141,000 residents. The edition covering the period until June 29 reported 711 suspected symptomatic cases that had still not been tested and 29 deaths of unconfirmed causes. Project coordinator Lidiane Malanquini affirms that the disease’s peak was in May. In the first half of June, there was a decrease, but with relaxation of quarantine requirements, cases started growing again in June.

“For every three symptomatic cases we identify, only one gets officially diagnosed. Without tests, we can’t even evaluate the capacity to attend to patients,” she says.

Underreporting, which hides the gravity of Covid-19 in these areas, also makes it difficult to convince the local population of the risks of the disease and the need to follow social distancing and protection rules, such as wearing masks. The activist Magda Gomes from the Rocinha Resists collective has no doubt that the pandemic will have long-lasting effects, with new waves of infection.

Together with other community leaders, she is working with researchers to create a specific plan to combat Covid-19 in favelas. The proposal was presented to the city health department, which did not embrace the idea. Now, it is in the final phase of approval for financial backing from the Rio de Janeiro state legislature, with executive coordination from Brazil’s national health institute, the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz), and participation from UFRJ, the Federal Fluminense University (UFF), the State University of Rio (UERJ), the Federal University of the State of Rio de Janeiro (UniRio) and the Catholic University of Rio (PUC-Rio).

“With research, it will be possible to know what is really happening in these places,” emphasizes public health expert and UFRJ professor Lígia Bahia.

Another member of the project, sociologist Marcelo Burgos of PUC, explains that the initial idea is to focus on five communities, including Rocinha, Maré and Alemão, with sites to attend to Covid-19 patients and centers for supervised social distancing, in addition to more general social support.

“Many people got sick and died in their own homes. They lived through this disease alone. And we’re going to live through a very critical moment when winter coincides with the flexing of isolation requirements,” says Burgos, who predicts a cost of R$16 million (US$2.9 million) for the initiative.

The city government says that on July 1, it initiated a second phase of testing in the favelas. It says it has taken other measures, such as telephone monitoring of people in high-risk groups. It also says that it is important to take into account that a portion of contaminated people are asymptomatic and thus cannot be officially counted, which it says is not only a problem in favelas.

*The Covid-19 in Favelas Unified Dashboard and RioOnWatch are both projects of NGO Catalytic Communities (CatComm).