This article introduces a series about energy justice and efficiency in Rio’s favelas.

There have long been different ways to compare energy systems. Most conventional metrics focus on cost: how much power does the system generate given the amount spent? How much does it cost to install and maintain?

Other metrics are related to inequality. Even as transitions are underway for energy systems to be more climate-friendly, might design choices within a system harm some people while benefiting others? Might design choices cost some people more than others? Might they silence or exclude historically marginalized groups?

This second group of questions falls under the theme of “energy justice.” Studies of energy justice look at the unfairness of energy distribution, both in terms of access to energy and in terms of how it is produced. This is particularly critical as we try to tackle the challenge in places with limited energy production and growing populations, not to mention what feels like growing unpredictability in a world marked by pandemics and climate change.

Researchers Kirsten Jenkins, Darren McCauley, Raphael Heffron, Hannes Stephan, and Robert Rehner reviewed the literature on energy justice in a paper for the journal Energy Research & Social Science and sorted the existing analysis into three distinct notions of justice: distribution, recognition, and procedure.

“Energy justice seeks to explore both production and consumption,” they write, calling for the energy challenge we currently face globally to be addressed as a political and socio-economic hurdle, beyond mere science, and via a human-centered approach. In a nutshell, “how we distribute the benefits and burdens of energy systems is preeminently a concern for any society that aspires to be fair.”

Distributional Justice: Who Has Access, Who Pays?

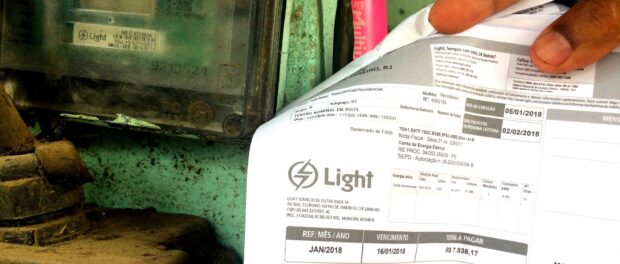

Considering distributional justice means looking at inequalities in how energy is distributed, including unequal access to energy entangled with issues of race, specific territories, and income, as well as unequal distribution of the income burden of rising prices. Whether the high financial cost to access this necessary service or living with pollution near the source of energy production, low-income communities tend to pay a disproportionate price.

“Distributional justice concerns not only the siting of infrastructure, but access to energy services too. From a consumption perspective, the fuel poverty agenda has revealed the uneven spread of burdens with regards to affordable access to energy services.”

The authors consider cases such as an effort to decarbonize Germany’s energy sector that benefited energy producers via exceptional tariffs while putting extra financial pressure on low-income communities. Another example of a distribution lens on energy justice considers that some populations may need more energy than others. There is growing recognition in England, Wales, and Scotland, for example, that groups such as the elderly and chronically ill need to have higher-than-average room temperatures.

Recognition Justice: Who’s Included, Making Decisions, and How?

Considering the recognition aspect of energy justice means examining who—and what kind of expertise—was consulted in the installation of an energy system. Were marginalized and local communities recognized and included? The authors write about a case in Scotland in which local communities opposed a commercial wind project. Instead, they built a community-managed one, which achieved clean energy for the region with local buy-in. Energy justice through recognition was served. Recognition justice is more than mere tolerance: it calls to acknowledge the divergent perspectives rooted in social, cultural, ethnic, racial and gender differences.

Misrecognition happens due to: “cultural and political dominance, non-recognition, and disrespect… [and] a long-standing tendency to stereotype the ‘energy poor’ and their ‘inefficient’ use of scarce energy and monetary resources… [The energy poor] have been typically treated as suffering from a ‘knowledge deficit’ with initiatives focused on the provision of information, economic subsidies and other incentives for increasing the energy efficiency…, yet hardly any attempts were made to discover the motivations behind consumption patterns or to engage with their interpretation of energy-related issues, and what kind of improvements and strategies they would envision. This failure to recognize specific groups not only creates injustice, but may also lead to the loss of potentially beneficial knowledge, values and stories, as we lose the insights of marginalized social groups.”

Procedural Justice: Is the Process Collaborative and Transparent?

Procedural justice with regards to energy is achieved when policymakers successfully work with local communities to implement more just energy systems. Local knowledge mobilization is critical due to local communities’ sensitivity to their ecosystems and territorial history built up over decades. Procedural justice goes beyond tokenism (the mere physical presence of local communities in decision-making spaces). It incorporates knowledge that can make a significant impact on successful policies. In Norway, for instance, the Sami indigenous peoples worked with planners, sharing knowledge about movements of reindeer populations in order to better determine the locations of wind turbines.

Procedural justice can also include increasing transparency about energy systems and diversifying the profiles of the people running energy companies or authorities. From a global perspective, the authors write that promoting collaboration, information exchange and transparency act as a “driver for encouraging more ethical and sustainable consumption practices as well as a society’s choice of energy production.”

Summarizing and offering a framework to those committed to energy justice, Jenkins and her colleagues write, “if injustice is to be tackled you must (a) identify the concerns in distribution, (b) identify who it affects, and only then (c) identify strategies for remediation in procedure.”

“Distributional justice recognizes both the physically unequal allocation of environmental benefits and ills, and the uneven distribution of their associated responsibilities… Recognition-based justice moves researchers to consider which sections of society are ignored or misrepresented… [And] procedural justice explores ways in which decision-makers have sought to engage with communities.”

They call for a “whole-systems approach” to energy which considers not only natural systems, but also social systems, arguing that a successful transition to a clean economy across the world requires information exchange and political rights. This allows for more informed decisions on how to best produce and consume energy as well as engage with policy.

This article introduces a series about energy justice and efficiency in Rio’s favelas.