This is the third article in a series covering the events of the 3rd Annual Full-Network Meet-Up of the Sustainable Favela Network, which happened online on November 7, 2020.

The Sustainable Favela Network (SFN) is a project of Catalytic Communities (CatComm)* with the aim of building solidarity networks, increasing visibility, and developing joint activities that support the expansion of community-based initiatives that strengthen environmental sustainability and social resilience in favelas across the Rio de Janeiro Metropolitan Region. The project began with the 2012 film Favela as a Sustainable Model, followed in 2017 with the mapping of sustainability initiatives in favelas across Rio. In 2018, the program organized local exchanges between eight of the most well-established community programs, followed by the 1st Annual Full-Network Meet-Up, launching the SFN formally on November 10, 2018. In 2019, the program organized another round of exchanges—this time open to all SFN members and to members of the public—in five favelas in Rio de Janeiro. The activities carried out in 2019 culminated in the 2nd Annual Full-Network Meet-Up. In 2020, the SFN’s Working Groups continued to meet—online, due to the coronavirus pandemic—carrying out a range of activities such as rounds of support (rondas afetivas), teach-ins, seminars, fundraising campaigns, a commitment letter for political candidates, and a debate with mayoral candidates. To close the year, the Sustainable Favela Network held its 3rd Annual Full-Network Meet-Up, summarized below and in this series, with the aim of bringing the network together, promoting the mutual strengthening of relationships among socio-environmental organizers, evaluating the SFN’s 2020 activities, and making plans for 2021.

Launch of the SFN’s Guide to Museums and Memories

The third activity of the Sustainable Favela Network’s 3rd Annual Full-Network Meet-Up was carried out by the Memory and Culture Working Group. Since 2019, the Working Group has been researching initiatives that seek to preserve and educate about memory in favelas and other peripheral territories of Rio de Janeiro.

The third activity of the Sustainable Favela Network’s 3rd Annual Full-Network Meet-Up was carried out by the Memory and Culture Working Group. Since 2019, the Working Group has been researching initiatives that seek to preserve and educate about memory in favelas and other peripheral territories of Rio de Janeiro.

The result of this effort was the launch of the Guide to Museums and Memories of the Sustainable Favela Network. This guide is the first of its kind and contains photos and information about 26 community museums spread throughout Rio de Janeiro and the surrounding area. Its objective is to show the importance of collective memory in the communities and to show how social museology has the potential to be a unifying and democratic tool, helping strengthen the feeling of belonging to a territory.

“There is no better shortcut to show the favela as a key part of the city than a community museum. Starting from the moment when a community establishes a museum, it leaves clear, for the whole world, that it values, that it recognizes the importance of its memory, and that it is deepening its feeling of belonging there,” said Theresa Williamson, of Catalytic Communities, that moderated the Meet-Up and opened the Guide’s launch event.

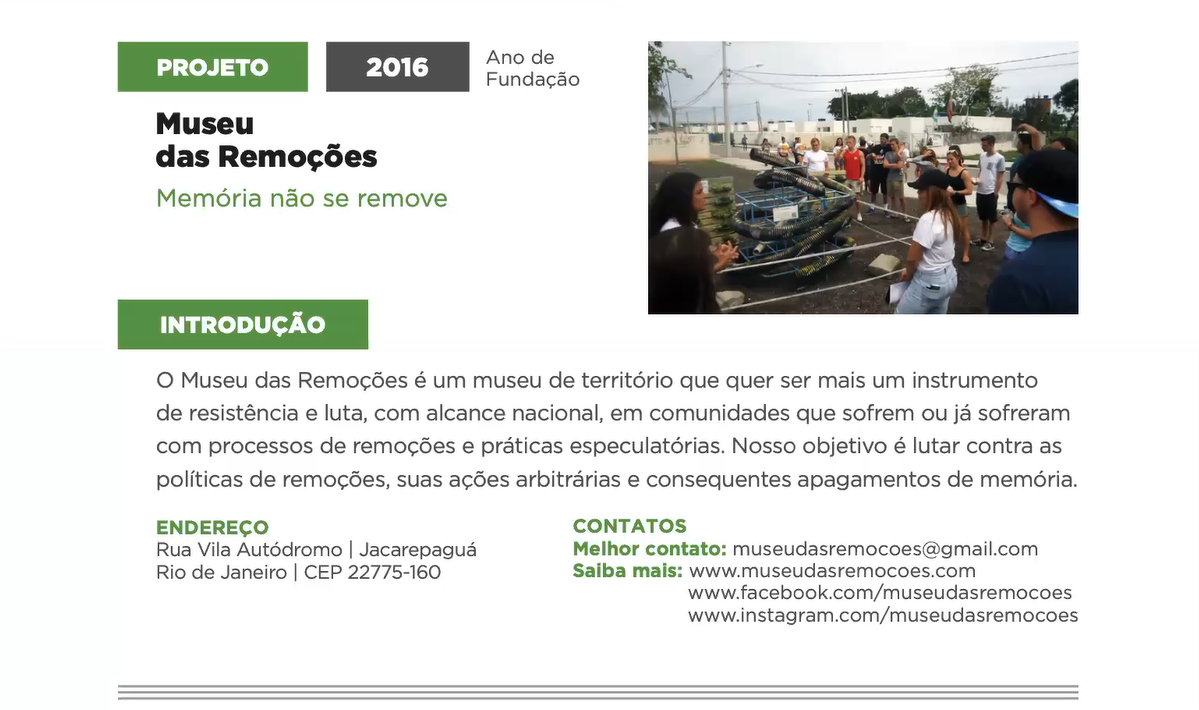

The preface, written by Maria da Penha, co-founder of the Evictions Museum in Vila Autódromo, introduces the collectively-written texts in the guide. Each memory project’s entry has a photograph, tagline, brief explanatory text, contact information, and address, in chronological order by the founding date of each project, due to the historic nature of a guide to memory. The creation of the Guide, according to Penha, leaves clear the reason why memory has such an important role in the lives of residents of favelas and peripheries: “Memory cannot be evicted!”

It is because of this that across and beyond the city of Rio, dozens of community museums, with experiences, curated collections, and archives flourish, especially in recent decades. The Working Group was able to identify 26 active projects over a year. This resulted in a map of community museums that can be accessed online here and seen below, as it appears in the Guide:

In a country that works so hard to hide the history of the struggle of favela residents, this guide demonstrates that people from the favela do not accept being silenced because, as Luiz Antônio de Oliveira of the Maré Museum in the Maré favelas said at the launch, “memory is something very visceral to us.”

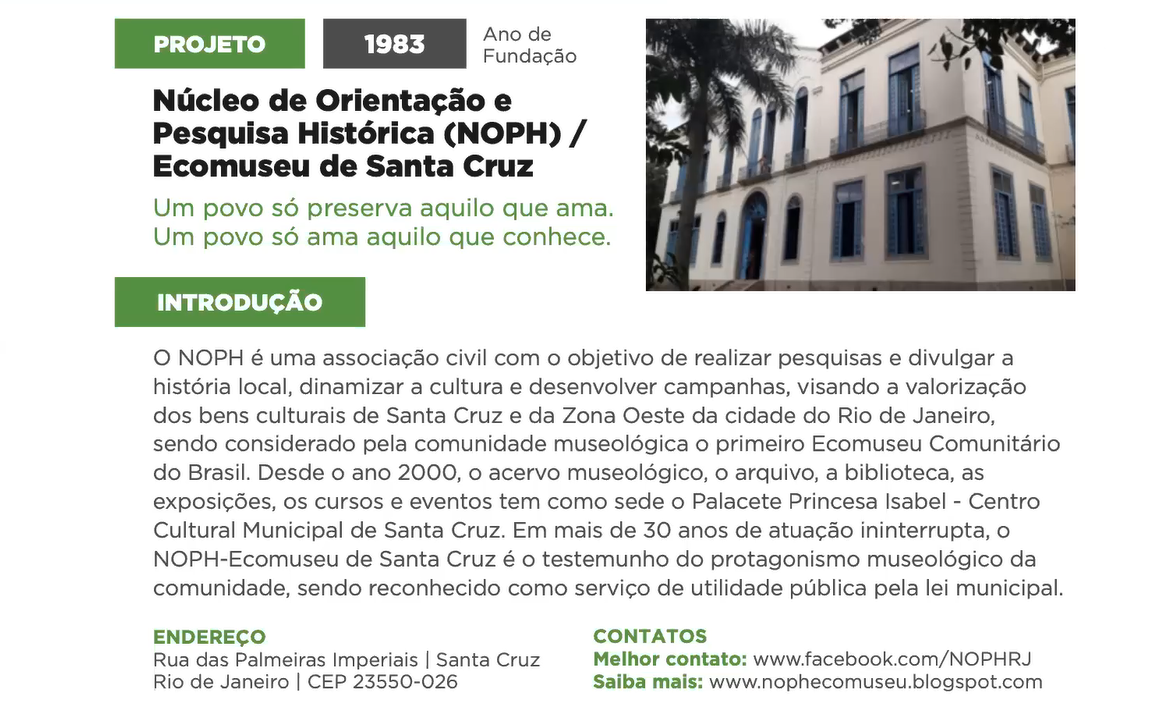

Beginning the individual presentations, José Renato Pimenta of the Historic Orientation and Research Nucleus of Santa Cruz (NOPH) said that although his institution was founded in 1983, there was a radical change in the way they dealt with historical assets. The NOPH founders originally intended to value the material assets of Santa Cruz; above all, Jesuit, colonial, and imperial construction. However, with the museological shift at the end of the 1980s and with the valuing of immaterial heritage, above all in the 1990s, NOPH became an ecomuseum, encompassing all of the territory of its residents. Pimenta explains: “The museum shifted to being not just one more building, walls, with material collections inside. The museum starts being the territory of the neighborhood and the population that inhabits it, that is, this puts the favela directly inside of NOPH… because 70% of the neighborhood of Santa Cruz is composed of favelas. So the population of the neighborhood starts to be a living part of the community ecomuseum…. the culture of the people of Santa Cruz become part of the ecomuseum. The favela becomes part of the living archive of the Historic Orientation and Research Nucleus of Santa Cruz ecomuseum.”

Beginning the individual presentations, José Renato Pimenta of the Historic Orientation and Research Nucleus of Santa Cruz (NOPH) said that although his institution was founded in 1983, there was a radical change in the way they dealt with historical assets. The NOPH founders originally intended to value the material assets of Santa Cruz; above all, Jesuit, colonial, and imperial construction. However, with the museological shift at the end of the 1980s and with the valuing of immaterial heritage, above all in the 1990s, NOPH became an ecomuseum, encompassing all of the territory of its residents. Pimenta explains: “The museum shifted to being not just one more building, walls, with material collections inside. The museum starts being the territory of the neighborhood and the population that inhabits it, that is, this puts the favela directly inside of NOPH… because 70% of the neighborhood of Santa Cruz is composed of favelas. So the population of the neighborhood starts to be a living part of the community ecomuseum…. the culture of the people of Santa Cruz become part of the ecomuseum. The favela becomes part of the living archive of the Historic Orientation and Research Nucleus of Santa Cruz ecomuseum.”

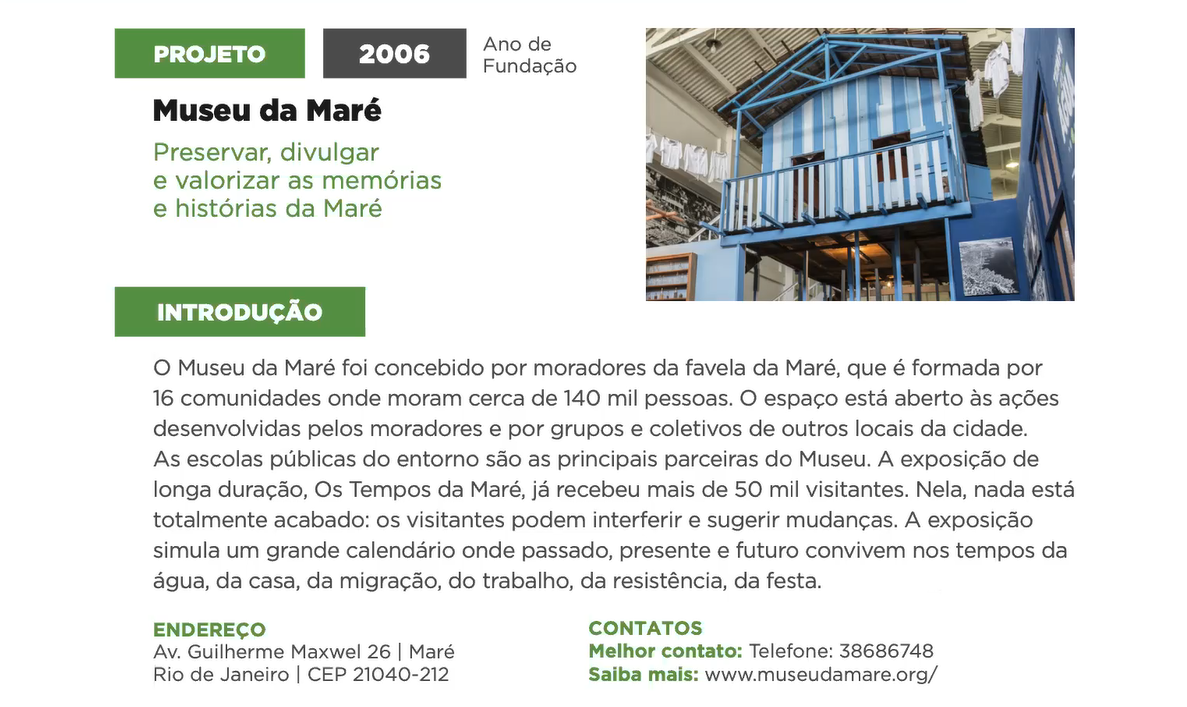

Next to speak, following the Guide’s (chronological) order, was Luiz Antônio de Oliveira of the Maré Museum, who spoke of its construction: “Memory becomes an important part of social transformation, in a very subjective way. It awakens a process of belonging, where a link is created with the territory. A link is created if you know the space where you live… this link generates belonging… [in that way] you break stigmas that much of society imposed on favela residents over the decades in the city of Rio de Janeiro. It is an extremely political instrument. The Maré Museum is our life. We talk about the Museum in the first person. We are not talking about someone else. We’re talking about us.”

Next to speak, following the Guide’s (chronological) order, was Luiz Antônio de Oliveira of the Maré Museum, who spoke of its construction: “Memory becomes an important part of social transformation, in a very subjective way. It awakens a process of belonging, where a link is created with the territory. A link is created if you know the space where you live… this link generates belonging… [in that way] you break stigmas that much of society imposed on favela residents over the decades in the city of Rio de Janeiro. It is an extremely political instrument. The Maré Museum is our life. We talk about the Museum in the first person. We are not talking about someone else. We’re talking about us.”

“In 1989, TV Maré was launched as a process of registering open sewage, the wounds, but also the history of the construction of that space,” said Oliveira. “This consolidated with the creation of [the NGO] CEASM in 1997/1998 and with the community prep course for university entrance exams, created for Maré residents, who, deconstructing these stigmas, enter university while still belonging to Maré and not denying Maré, as a sociability strategy… It is important for Maré residents to know that the pollution of Guanabara Bay in the region where they live is not due to the construction of houses on stilts [of old Maré], of the residents who threw trash and took care of their needs in the water. It is important to know that the area of the [nearby] Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) was created by connecting eight islands through infills. What causes more environmental impact? The Maré Museum is born in this space… in 2006… it is born from this incredible necessity of the residents of Maré to have their space. And the museum is anthropophagic, it devours!”

The presentation of Francisco Valdean of the Maré Traveling Museum of Images (MIIM) reinforced this thesis that memory is a central instrument for the social transformation that is desired, from the grassroots. The project is “the youngest child in the catalog,” Valdean said. It is a museological project created by the artist in August 2019, during his doctoral work in art at the State University of Rio de Janeiro (UERJ), where he founded the mini museum, always thinking of images as a symbolic field related to Maré.

The presentation of Francisco Valdean of the Maré Traveling Museum of Images (MIIM) reinforced this thesis that memory is a central instrument for the social transformation that is desired, from the grassroots. The project is “the youngest child in the catalog,” Valdean said. It is a museological project created by the artist in August 2019, during his doctoral work in art at the State University of Rio de Janeiro (UERJ), where he founded the mini museum, always thinking of images as a symbolic field related to Maré.

The mini museum is, as its curator said, “an infinite exposition” and is based in a shoebox where there are three exhibitions: images in monocles, photo negatives, and pictures of uncommon life in the favelas of Maré, the majority on 10×15 photographic paper. It was founded in a Facebook post during a barbecue in Vila do Pinheiro and still “is a museum in a state of invention,” according to Valdean. He says that one of the proposals of the traveling museum is to circulate in various spaces of Maré and other territories and spaces in Brazil and abroad, always carrying the symbolic dimension of the territories linked to their visual representations.

“When showing the exhibitions in bars, barbecues, streets and plazas before the pandemic, what is clear is that the inventive part of this museum came from this contact with people… One of the first things I noticed is a matter of extreme relevance for museology and for art. ‘But, man, is this a museum?’… asking if there was a possibility that a museum—which we know in monumental buildings—could function in a shoebox… there were also a lot of people who looked at that box and said, ‘Wow, this is a museum!’, with wonder… At a school in Vila do Pinheiro, when I introduced it to a large number of students, a student raised his hand and said ‘My grandma is a museum!’, And I asked, ‘Why is your grandmother a museum?’, And he replied ‘Because my grandmother is full of stories and she files her photographic material in a box too!’, So I realized that part of the museum occurs in contact with the residents.”

There is also a photographic exhibition on the MIIM website composed of the “work of eleven artists from Maré. [The exhibition] takes a look at Maré in the Pandemic and this very complicated moment for the favelas,” said Valdean.

Then, Penha, from the Evictions Museum, took the floor, praising the Network and the creation of the Guide. According to her, it is “incredible work for the museums that resist,” an example of collective democratic work even in the middle of the pandemic. She then presented the trajectory of the Vila Autódromo memory project.

Then, Penha, from the Evictions Museum, took the floor, praising the Network and the creation of the Guide. According to her, it is “incredible work for the museums that resist,” an example of collective democratic work even in the middle of the pandemic. She then presented the trajectory of the Vila Autódromo memory project.

As presented by Penha, the Evictions Museum “is born from the rubble of eviction, a very difficult removal inside Vila Autódromo. It is born resisting against a whole violent process from City Hall, from the state government, and even from the Judiciary. We seemed to be at war… [The Evictions Museum] just happened over the course of the eviction. In 2015 we started to consider [creating it]. And in May 2016, this museum of territory and resistance was launched… It was conceived as a way to take hold of the culture, to continue fighting for our rights to be respected. And it was born with two proposals: to remain in the community, to be a tool to fight evictions, to show that we wanted to stay in this space, that we loved this space, that we were entitled to this territory, that we were being violated. And to maintain the memory of those who left, who lived in this community for so long. And to tell our story. We understood the importance of continuing in that territory and telling our own story.”

Penha concluded that even with only 20 families remaining from the hundreds who lived in Vila Autódromo before City Hall’s advances, the community remains strong and understands that the museum is one of its roots in its territory.

“This museum shows everyone that we managed to stay… this museum is all that remains of Vila Autódromo… We can say ‘this territory is mine’, pass our history on to other populations, communities that want to resist, who want to stay in their territories… and to show that the favela is part of the city… Taking possession of social museology for us to have a voice… This Guide gives us visibility, when we are generally marginalized. Shows the knowledge of the favela to others. It is important that each favela tell its own story.”

“This museum shows everyone that we managed to stay… this museum is all that remains of Vila Autódromo… We can say ‘this territory is mine’, pass our history on to other populations, communities that want to resist, who want to stay in their territories… and to show that the favela is part of the city… Taking possession of social museology for us to have a voice… This Guide gives us visibility, when we are generally marginalized. Shows the knowledge of the favela to others. It is important that each favela tell its own story.”

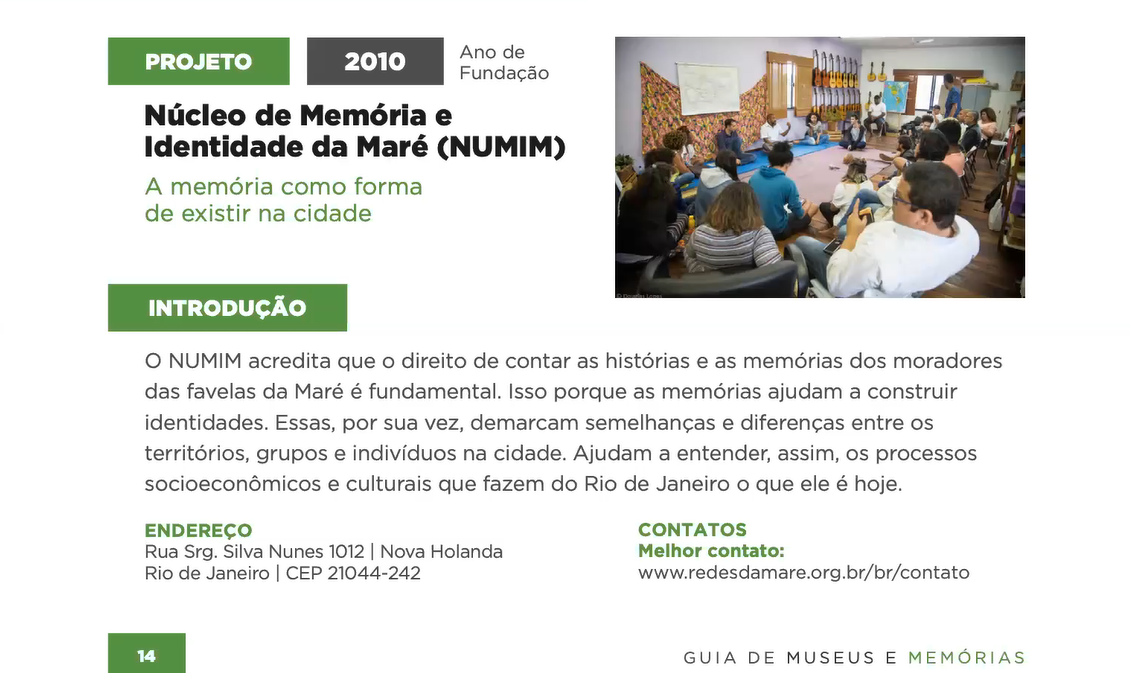

The panel ended with a remarkable speech by Tereza Onã from the Maré Center for Memory and Identity (NUMIM), an initiative of NGO Redes da Maré, which has, since 2006, been carrying out projects aimed at preserving the memory and history of the favela in partnership with Azulejaria. She started by introducing herself: “I am a black woman in the diaspora, and memory is essential, but in the case of the black population, where our history has never been told, memory is an impressive stimulus… orality is a foundation for our population.”

Onã calls attention to the focus on orality in black production, and speaks about storytellers, especially older ones, as a living museum of black history in the diaspora. She helps carry out the project Griots of Maré, a living initiative of collective memory of the favela.

One of NUMIM’s initiatives is the Maré Open-Air Museum, a collection of memories from residents of all age groups. It has created a route made out of tiles decorated with phrases from residents, in a “very beautiful” structure, according to Onã. It is a circuit of memory works that begins in Parque União and ends at the Parque Ecológico in Vila do Pinheiro. It even crosses over borders imposed by conflicts between rival groups of drug traffickers.

The Maré Open Air Museum is the result of twelve years of work by NUMIM aimed at preserving the memory and history of the favela. The collection of testimonials from residents produced by NUMIM is digitalized, with the aim of making the material available for consultation. In addition to the virtual space and the territorial route, NUMIM is organizing a documentation center that will be open for consultation, research and exchange of researchers from inside and outside Maré. The idea is for the museum to be “a collection of residents’ memories… organized in a tiled circuit and with poetry from residents out in the open, in Maré,” said Onã, adding, “due to the pandemic, The Maré Open Air Museum has yet to open its first exhibition, which will only happen when it is appropriate.”

In addition, the birthday of Emilia Maria de Souza of the Residents and Friends Association of Horto and the Horto Museum, which took place on the same day as the Full-Network Meet-Up, was celebrated. Emilia thanked everyone for the birthday wishes, her friends and the orixás, in addition to congratulating the SFN for all that was done during the year and the Working Group for the Guide and, above all, for not stopping during the pandemic, for continuing to organize.

The feeling that dominated the morning launches of November 7, of the SFN Catalog and Guide, was that despite the pandemic, the power of creative organization continues, even if remotely. Whether in sustainable community and local handicraft production, understanding solid waste not only as an environmental urgency, but also its potential for collective solidarity, self-esteem, and income generation; or in the pride and need for recognition and appreciation of popular collective memory, as a democratic tool for empowerment and social transformation.

It became clear that, for many, community organizing is synonymous with life. Feelings that will also be present in the actions that the Working Groups realize also in 2021.

Watch the Launch of the SFN Guide to Museums and Memories:

This is the second article in a series covering the events of the 3rd Annual Full-Network Meet-Up of the Sustainable Favela Network, which happened online on November 7, 2020.

*The Sustainable Favela Network and RioOnWatch are both projects of Catalytic Communities (CatComm). The Sustainable Favela Network is supported by the Heinrich Böll Foundation Brazil.