This article is the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” Follow our Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas series here.

The place is a church, one of those that are universal, global, international, but never local. At a certain moment, a young man stands up with his hands behind his back, speaking in a distorted voice as he walks toward the altar. The pastor asks, “Who’s there?” Immediately, a spirit identifies herself, “It’s Pombagira!” She goes on to say that she is taking the man whose body she has entered—through demonization or possession, to use the usual jargon—into a “life of homosexuality.” The scene is so familiar in Brazil that we can claim to have seen it on TV, in person, or heard the exchange on the radio.

We know that all nations, over time, developed a relationship with what they believed to be sacred. For certain African peoples, elements of nature such as rivers are sacred. For some Asian peoples it has been mountains. In the case of some indigenous peoples, it is found in the stars. For the Messianic Church it is in the sacred soil of Guarapiranga (a reservoir south of São Paulo). And for evangelical Christians, mountains are popular points of prayer and vigil. Some of these sacred names and stories do not even exist anymore. And still others will appear throughout history. Why would only one be correct? And what criteria determines that one religion is right and another wrong?

Did you know that your religion did not exist until recently? Brazil’s religious genesis is based on European Christian colonization. However, since the arrival of the Royal Family, in 1808, other religious groups have been able to develop their faith on Brazilian soil. Such is the case with Anglicans and Kardecist Spiritists. Throughout the 19th century, in the central region of Rio de Janeiro, so-called “macumbas cariocas”, a name widely used to refer to religions of African origin in those days, were established. These macumbas were mainly attended by blacks and poor people who lived in nearby tenements, or in the first favela, now known as Morro da Providência. These macumbas cariocas became places of spiritual development and cultural resistance to the constant violence imposed on black bodies and what they represent culturally in Brazil. It is important to note that Umbanda, a religion formed at the beginning of the 20th century in the city of São Gonçalo, in the state of Rio de Janeiro, had a notable growth among blacks and the poor, as well as earning a place among Rio’s white middle class.

As the Pentecostal movement grew, churches such as the Christian Congregation in Brazil (1910), Assemblies of God (1911), Brazil for Christ (1955/1956) and God is Love (1962) emerged and were formalized, above all, among the poorest. The strong verbal attacks on the religions of African origin gained traction, causing blacks and the poor to join these religious organizations, thus creating new churches, called neo-Pentecostals, such as the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God (1977), International Grace of God Church (1980), Reborn in Christ Church (1986) and Universal Church of God’s Power (1998). We have mentioned the biggest churches here but would not be able to list the many others that started but did not continue their work for different reasons. This does not happen solely with evangelical churches. Several other religions disappeared as the culture and the people that supported them also dwindled. The religions of the indigenous peoples of Brazil and of the American continent are examples of how colonial violence aims to exterminate worldviews that do not contribute to its expansion.

That’s right! Religion is a manifestation of a specific people’s culture and is connected with these people and with the territory where they live. Religion is the result of a people’s relationship with what is sacred to them, and of this sacred with what is sacred to others. Have you noticed that the church on your street is probably different from a church with the same name in another neighborhood, at the other end of the city?

Unfortunately, we were taught that the truth is in our hands, and this is detrimental to all of us! Can you imagine if everyone thought the same? What a pain it would be to live in this world! Diversity makes our world beautiful and makes each of us have has a different priority, perspective, and point of view on the same topic.

Since then, some people have decided to elect a common enemy to affirm their truth as the only possible truth, and have used an existing structure to make it easier to convince others: structural racism! In her book Plantation Memories: Episodes of Everyday Racism (2008), psychologist Grada Kilomba says that “racism is revealed at a structural level as Black people and People of Color are excluded from most social and political structures. Official structures operate in a way that privilege their white subjects, putting members of other racialized groups at a visible disadvantage, outside the dominant structures. This is what is called structural racism.”

Amanda Santos, a salesperson and resident of the AP do Itararé, in Complexo do Alemão, says in an interview that racism “is a way of demonstrating, of showing that white people, who consider themselves a superior race, even though they obviously aren’t, are trying to wipe out blacks and other ethnicities.”

When we believe that a certain “race” is better than another, it becomes natural to defend and give preference to one over the other. That is why racism is so toxic to our society. It divides and harms certain groups, while giving advantages to others. We all know how the Brazilian State treats white and black people differently. How many white homeless people do we see every day? And how many black doctors graduate from Brazilian public universities? A doctor who believes that white people are better than black people will treat whites with more dignity. A religious leader who believes that one religion is worse than another, will teach their followers to fight other religions in order to eliminate them, judging them as heretical practices, black magic, or witchcraft. We have examples of this in the Brazilian legislative branches, where bills are constantly being voted to hinder the practice of Afro-Brazilian worship. These laws confuse and create animosity between society and practitioners of African religions. In 2019, the Federal Supreme Court ruled that animal sacrifice in religious cults of African origin are constitutional, ending several attempts to criminalize the ancestral feeding practice of the terreiro people (practitioners of Afro-Brazilian religions).

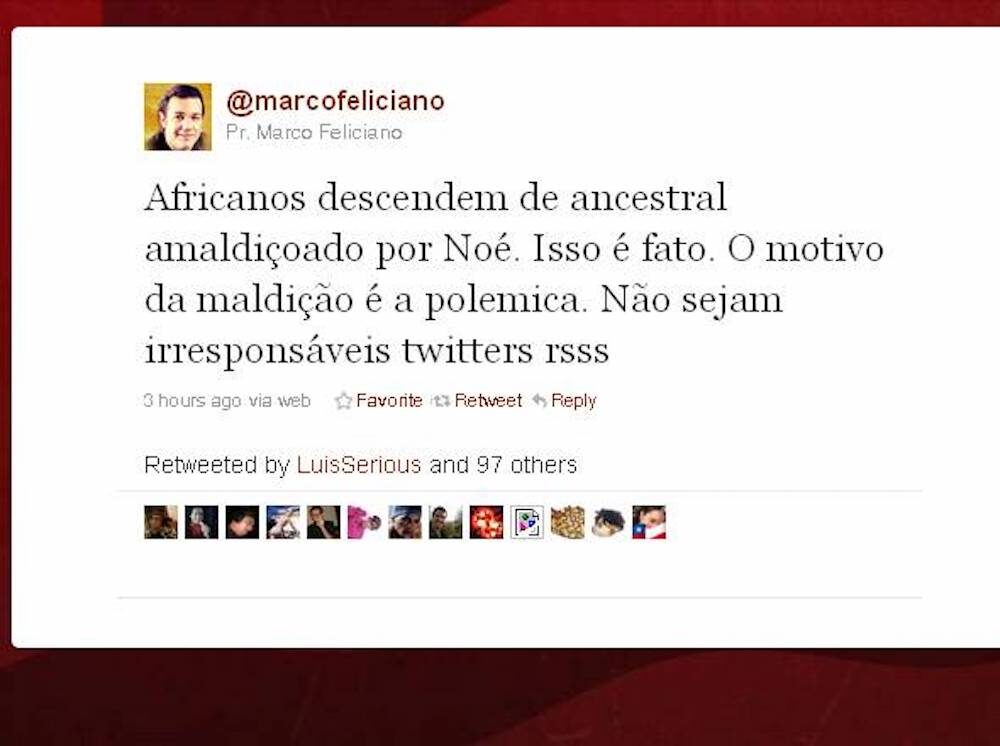

Africans descend from an ancestor cursed by Noah. That is fact. The reason for the curse is controversial. Don’t be irresponsible twitters rsss

This message was posted on Twitter by federal congressman Marco Feliciano (PSC-SP). Shortly after the negative repercussion of his tweet, he deleted it. But even during services televised from his church, he admits and reaffirms his racist speech as theology.

When did we start finding this type of behavior acceptable?

Speeches like these persuade people to perceive practitioners of African religions as cursed, less human, or as the fruits of evil, which makes them vulnerable to all types of violence.

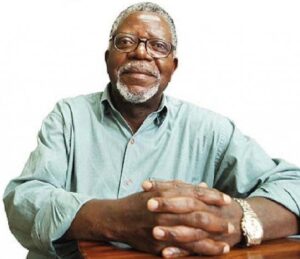

In A Conceptual Approach to the Notions of Race, Racism, Identity and Ethnicity (2004), Professor Kabengele Munanga conceptualizes racism as “a belief in the existence of a natural hierarchy of races, through the intrinsic relationships between the physical and the moral; the physical and the intellectual; and the physical and the cultural.”

In A Conceptual Approach to the Notions of Race, Racism, Identity and Ethnicity (2004), Professor Kabengele Munanga conceptualizes racism as “a belief in the existence of a natural hierarchy of races, through the intrinsic relationships between the physical and the moral; the physical and the intellectual; and the physical and the cultural.”

In other words, we can also understand racism as the belief that certain people are better than others because of their origin, or the color of their skin. The set of characteristics that we call race is built in our imagination mainly through education, science, art, theology, landscape, etc.

In a religious temple, whenever we see a direct mention to another religion as something negative, we need to ask ourselves the question: who is this benefiting?

Pedir a benção pras nossas mais velhas é uma coisa que aprendemos desde cedo no terreiro. Aprender com os mais experientes é um fundamento também do cristianismo. Mas na verdade, tudo isso é ensinamento do povo negro, em diáspora, desde sempre: nossos passos vieram de longe.

— Pastor Henrique Vieira (@pastorhenriquev) November 13, 2020

In the terreiro, I learned the importance of faith for black people. We also dream of a different world within the churches. Why can’t we work together? Here’s what it’s about: when we hold hands, we make faith circulate, we make axé circulate. And collectively we dream of a fuller, freer, more joyous life!

Asking our elders for their blessing is something we learn early on in the terreiro. Learning from those with more experience than us, is also a foundation of Christianity. In fact, these are all teachings of Africans in the diaspora since forever: our steps come from far away.

Certain people have waged crusades and holy wars against a common enemy. The enemy has different ethnic origins yet has been very well defined geographically: it is from Africa. These enemies also have a color of skin or a color of faith. The victims of racist religious intolerance are (almost) always the sacred black entities of religions brought from Africa. How come you have never seen Shiva, Vishnu or Thor “manifest themselves” in these churches? Why are the chosen enemies always from a single religious origin, hailing from a single part of the world? This phenomenon is called racism. And when it relates to religion, it reveals itself as religious racism. It makes people believe their truth is better than the truth of another, making them deem the other and their supposedly demonic and impure beliefs as the enemy, without questioning why it is always the same spiritual entities manifesting and being fought and expelled in church services, always in the name of a white, blue-eyed Jesus.

Racism naturalizes oppression of black people in all areas of their lives, including in their spirituality and faith. Since colonial times, we have observed systematic violence against people of Afro-Brazilian religions, such as Umbanda and Candomblé, including attacks on temples, intimidation when public spaces are used for rituals, or the bullying of initiated children in schools. A clear example of this type of violence was when a young girl, Kailane, 11, was hit by a stone while leaving her place of worship with her family, in the North Zone of Rio, in 2015.

In Brazil, the Ministry of Women, Family and Human Rights is responsible for the Disque 100 (Dial 100) hotline responsible for registering cases of religious intolerance, among other occurrences. According to official Disque 100 data, of all cases of religious intolerance in 2017, those against Afro-Brazilian religions totaled 144, while against Catholics totaled 31, and Evangelicals 27. In 2018, the most affected groups were, again, Afro-Brazilian religions (147), Jehovah’s Witnesses (31), and Evangelicals (23).

We must remember that Brazil is a secular country, and as such, does not officially claim any faith. In addition, discriminating someone based on their faith is forbidden. It is a crime according to Law 7716, of January 5, 1989, and amended by Law 9459, of May 15, 1997.

The best way to guarantee one’s freedom is by looking after the freedom of others. To avoid major problems, when you feel violated or discriminated against in your religious freedom, gather evidence such as videos, audios, printed screenshots from social media; witnesses of public threats, aggressions and/or slander, among others. And, in doubt, immediately contact the authorities: Dial 100!

About the author: Jeferson Rodrigues is 34 years old from Complexo do Alemão. He graduated as a teacher in geography at the State University of Rio de Janeiro (UERJ) and is a specialist in Public Administration at CEPERJ. He uses social media to talk about race and spirituality. He maintains the Dide YouTube channel where he speaks on racial issues among members of Afro-Brazilian religions.

About the artist: Natalia de Souza Flores was born and raised in Rio de Janeiro’s North Zone and is a member of Brabas Crew. With a degree in Graphic Design from Unigranrio in 2017, she has worked as a designer since 2015. She launched a magazine of collective comics called ‘Tá no Gibi’ in 2017 at the Rio Book Biennial. Her main themes are based in African culture, using cyberpunk, wicca and indigenous elements.

This article is the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” Follow our Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas series here.