This article is the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” Follow our Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas series here.

Brazil’s affirmative action policy, established in 2012, opened the doors of higher education for black and brown students, people from low-income backgrounds, and students from public schools, modifying the profile of those attending public universities in the country. Almost a decade after its approval, numbers show that young black people are already the majority in Brazilian universities, increasingly reflecting the make-up of Brazilian society, where more than half of the population self-identifies as black or brown.

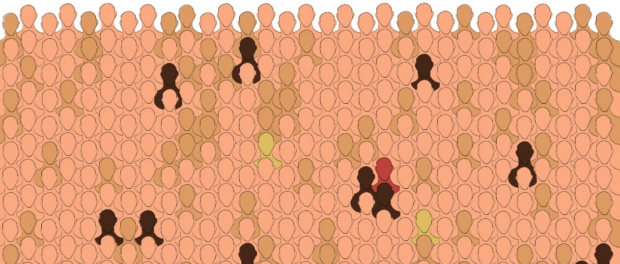

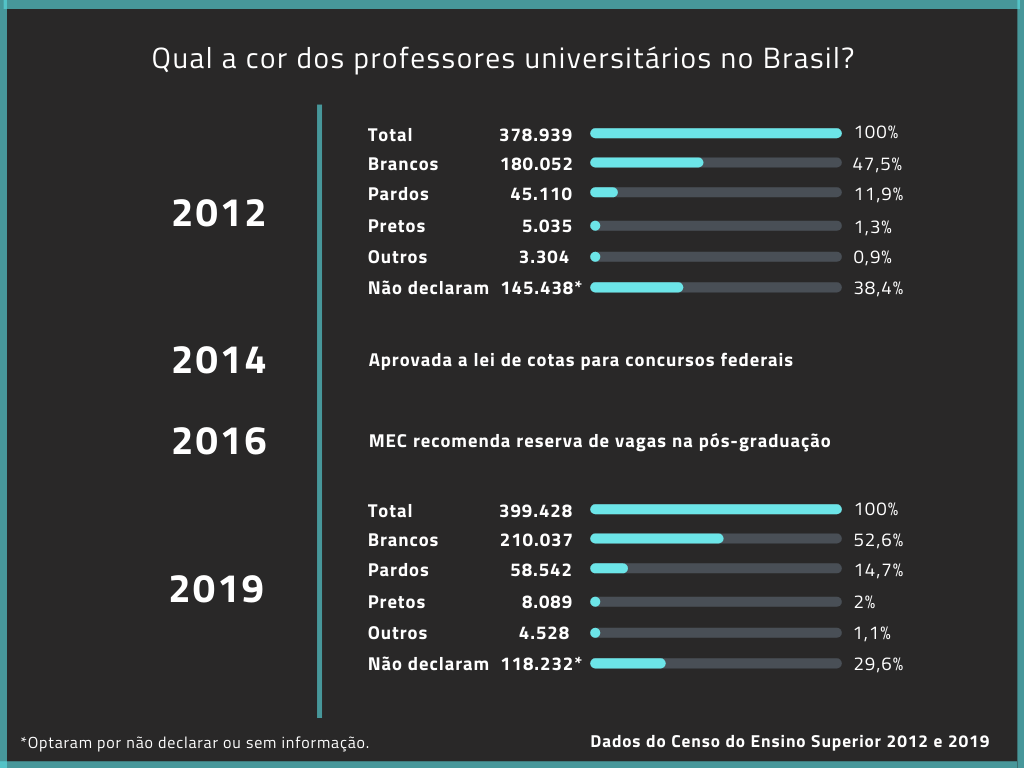

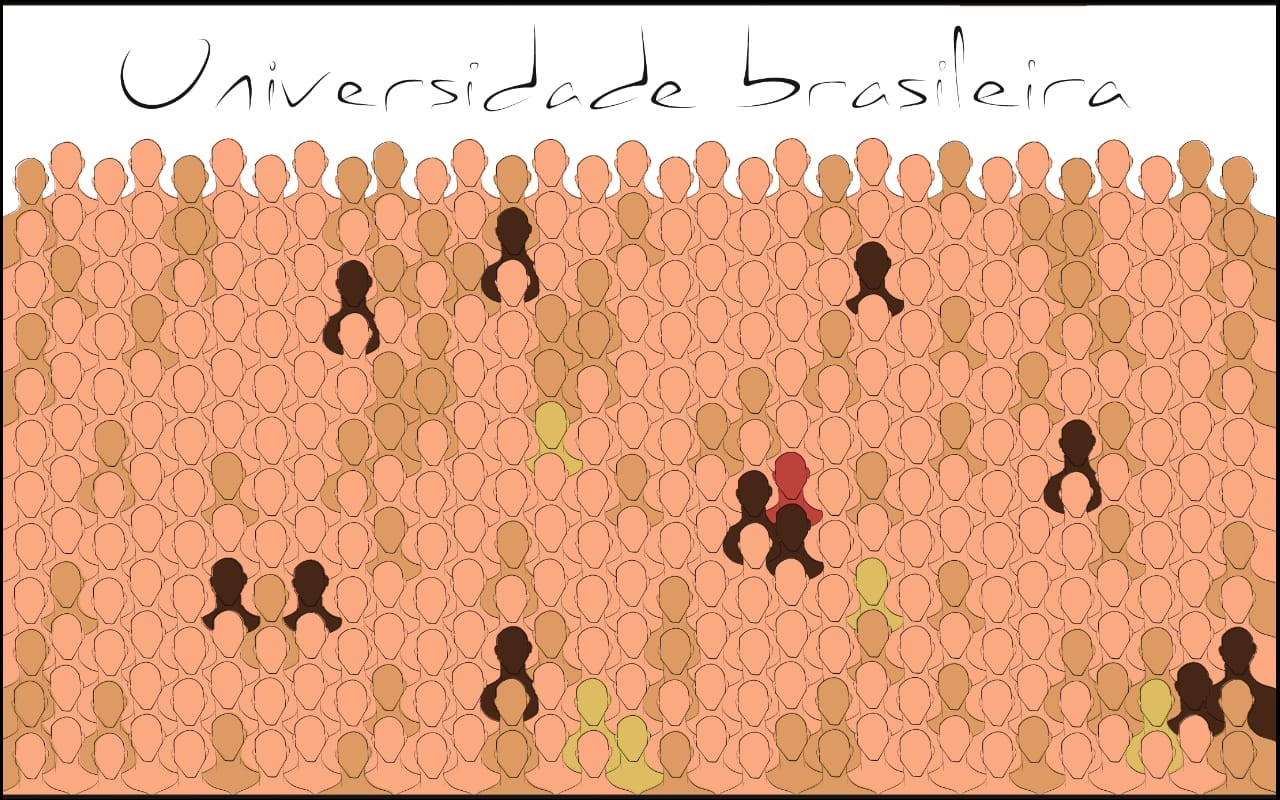

With more non-white students—black, indigenous and others—reaching higher education, the expectation was that the change in profile would also reach the faculty, which is still far from happening. In Brazilian universities, teaching is still a profession exercised, mostly, by white men, according to data from the last Census of Higher Education, carried out in 2019 by the Ministry of Education (MEC). In the universe of almost 400.000 university professors, approximately 67.000 (17%) self-identify as black or brown.

With more non-white students—black, indigenous and others—reaching higher education, the expectation was that the change in profile would also reach the faculty, which is still far from happening. In Brazilian universities, teaching is still a profession exercised, mostly, by white men, according to data from the last Census of Higher Education, carried out in 2019 by the Ministry of Education (MEC). In the universe of almost 400.000 university professors, approximately 67.000 (17%) self-identify as black or brown.

The low number of black professors in universities means leads to subtle and daily discomforts for the few that make it to these spaces. For Flávia Rios, a sociologist and professor at the Fluminense Federal University (UFF), seeing a black person as a professor still causes astonishment. She says she has heard comments about not “looking like a professor” a few times. In another situation, during a department meeting with other teaching colleagues, she was confused for a student.

“Black people suffer these embarrassments at universities because no one expects them to be faculty members. So, it’s quite curious to hear university employees, outsourced or otherwise, say that I don’t have ‘the look of a professor.’ They don’t say that because they’re discriminating against me, they say it because it’s not something they’re used to seeing. They’ve been working there for years and years without ever, or hardly ever, seeing a black faculty member,” ponders the professor.

Hailing from humble origins, Rios was the first person in her family to receive higher education. Her admittance to the University of São Paulo (USP) was not by chance but determined by the accommodations offered by the institution at the University of São Paulo Residence Hall (CRUSP). At that time, the debate about affirmative action policies was still far from becoming a concrete measure. Like most universities, USP, in the beginning of the 2000s, was even more of an elite, white space than it is today. Rios represented the opposite profile of the majority of students: she was black, from a public school, and her family had very few years of study.

The presence of black and brown students in university classrooms became more common after the passing of Brazil’s national affirmative action law, in 2012. These groups’ access to universities, in Rios’s view, represents an effective policy in tackling inequalities, even if a lot still needs to be done to guarantee their permanence in school, and the insertion of black students into the job market after graduation.

“A person coming from a working class background, or that, for example, has no formal training or even a stable job, if that person’s child is admitted to university, the chances of that child having a better life, a profession, earning a better living, providing better chances for their family, and for the family they’re going to build, or even for themselves, are much greater than if the person simply remained within their own social class,” says Rios.

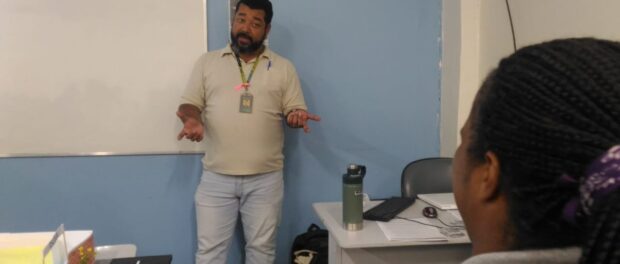

Professor Luiz Fernando Villalba’s grandmother was well aware of this. She studied only until the fourth grade, but always emphasized the importance of studying to her grandson. His major motivator was also the person that saved every last penny to pay part of Villalba’s private university fee. The advertising graduate did his undergraduate at Estácio de Sá University, the same private institution where he works today as a professor. His journey into teaching, however, was neither fast nor easy.

“I always say that between me getting my first undergraduate degree, and entering a classroom as a university professor, it took ten years. And what did I do in those ten years? Did I sit around waiting? No. I worked as a factory floor worker in Belford Roxo; I sold mobile phones in a phone shop; I was a salesman for a business that works with public biddings in the IT area. Then I became a photographer for the university where I work at today. I couldn’t wait around for something to happen until I could get into the classroom. I needed to get by, but I was always focused, I never lost sight of what I wanted [to be],” Villalba recalls.

He spent a few years as a photographer at the same institution. In this period, Villalba got a second degree, in History, and a certification that qualified him to teach. His first contact with teaching came with a short course, taught during a school break. Later came the opportunity to teach a full university course, until he became part of the institution’s regular faculty, in 2012. The transition from administrative worker to professor was a dream come true for him, but Villalba says that the switch was puzzling for most of the institution’s professors.

“How many, countless times, did I walk into the faculty room, say good morning and no one answered? How many times did I say good night, and no one replied? Because they were used to seeing me as the guy that takes photos, the photographer, the photo boy. How many times did I take pictures for the professors’ ID cards? How many events did I cover? How many photos of the campus did I take?” questions Villalba. According to him, it took a while for his presence to be seen as normal in spaces frequented only by professors.

The reduced number of black people pursuing a teaching career at the university level is also a reality experienced by Villalba in the private institution where he studied and currently works. The professor, who teaches courses for five distinct majors, recounts that he has often found himself as the only black faculty member in a given department. The current scenario is not that different from the start of the 2000s, when he studied advertising at the same institution. Villalba says that he does not remember having had a professor that can be recognized as black or brown during his studies.

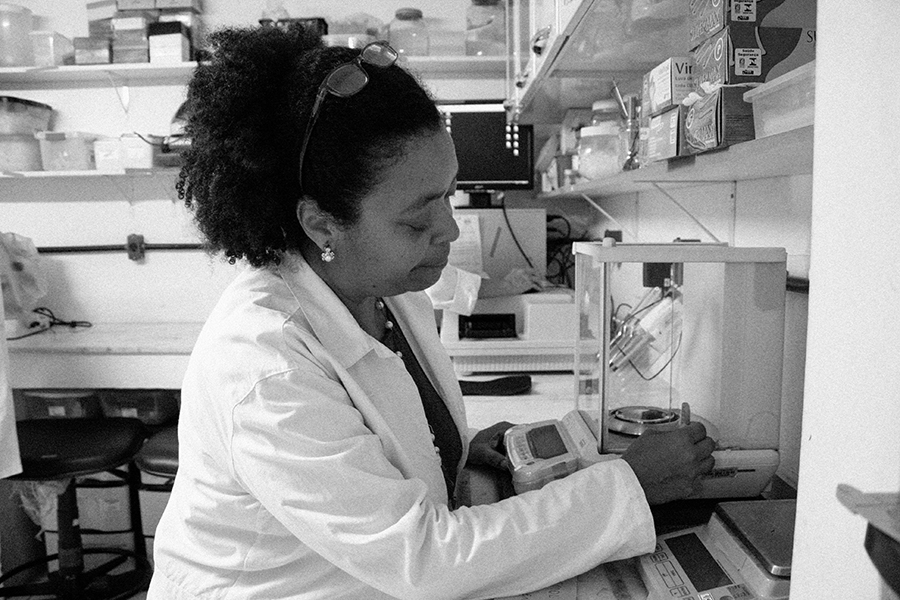

Noticing yourself as the only black person in a certain environment is a well-known feeling for black and brown professors throughout their studies and in their professional lives—a feeling that Professor Helena Castro took a while to notice. Adopted by a white woman before she was two years old, Castro says she only became aware of her blackness as an adult. According to her, she never noticed if she was a single presence in places because, up to that point, the racial issue was not a part of her. As a child, Castro was taught that her successes and failures were an exclusive consequence of her efforts. The awareness of her blackness and the understanding of the effects of racism were issues absent from a large part of her life.

For Castro, the awakening of her racial identity happened when she spent a year during her PhD program at the University of California, in the United States. She recalls something that happened after she left one of her classes. On her way home, walking down a dark street, she bumped into a black man who stopped her. The professor says that, at first, she was quite scared, but was surprised to be called “sister” by him. The man asked what she was doing out alone, late at night, and seemed surprised when she told him about her doctorate.

“He approached me as a sign of racial recognition. I told him of a situation that is rare in the United States, which is of a black person attending graduate school, and he just embraced me with words of acceptance, saying something like, ‘For Chrissakes, hang in there!’ That’s when color hit me and, from then on, I started to look around and noticed that, in the building where I studied, at the University of California, which was just huge, there was only one black person. That got me thinking about the scientific realm. For instance, I went to a biotechnology conference and was presenting a poster and a guy came up to me and said: ‘I’m so happy that you’re here!’ And I understood that [his happiness] was because I was black,” observes Helena Castro, professor of Biology at UFF for almost two decades.

How Many Obstacles Between an Undergraduate Degree and Teaching?

The years of study needed to become a university professor generate costs that, at times, students and relatives do not manage to cover. Beyond the direct costs, there is the time dedicated to qualifying that are not being consumed by paid work. For this reason, research grants and incentive policies are crucial so that black students or those originating from poor families can dedicate themselves to their studies.

“Funding cuts impact financial aid policies directly, both for undergraduate and graduate students. Meanwhile, policies have been weakening institutions that fund research, which has a direct impact on any affirmative action policy, especially at the graduate level. Policies restricting resources not only limit research directly, but prevent low-income students from pursuing an academic career, since they cannot afford to remain as researchers at universities,” evaluates sociologist Flávia Rios. In the professor’s view, the budget cuts in science and education have a direct impact on the entry and, particularly, on the permanence of black and poor students in the graduate programs at public universities.

Guaranteeing students’ ability to complete their studies is also a concern of both Villalba and Helena Castro. The two highlight the low amounts paid by master’s and doctoral grants, which demand exclusive dedication from the student. In other words, the student cannot have another professional activity to supplement their income and the grant amount has not been revised since 2013. For professor Helena Castro, from UFF’s Institute of Biology, financial difficulties faced during one’s studies help determine the profile of the teaching staff in higher education.

“Many vacancies in higher education require a master’s or a doctorate, while grants have not increased in ages. That is enough to discourage black people from getting to this point in their education and to qualify to teach. Then, there’s another matter, as a master’s or doctoral student, do you have a guaranteed job? No. Your only guarantee is a job search,” says Castro.

The financial issue impacts, especially, black and brown students because, in Brazil, poverty has a color. More than 55% of the population self-identifies as black or brown, but these people do not proportionately occupy all spaces. When we look at the country’s poorest population, 75% are black. The same group becomes a minority—28%—when we look at the richest portion of the population. These data are from the last Social Inequalities Due to Color or Race in Brazil Report, published in 2019 by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE). Furthermore, according to the study, one of the explanations for this income gap between white and black people may lie in the unequal access to studies and management positions in the job market.

After adoption of the affirmative action policy at the undergraduate level, bolstering the entrance of black and brown students into public universities, a MEC administrative rule, approved in 2016, recommended that vacancies be reserved at the graduate level for black, indigenous and people with specific needs. Despite not being mandatory, Rios says that a large portion of programs are, little by little, incorporating the measure.

However, the guarantee of access to studies will not be enough to change the profile of the country’s body of professors. For this reason, a law of affirmative action for federal civil service contests was created in 2014 designating nearly 20% of vacancies to black and brown candidates. The law’s objective, according to Rios, is to tackle the inequalities in careers, not only between professors, but taking into account all technical services at federal institutions. Seven years after its approval, and nearing its expiration, however, little has changed in the scenario.

“It seems that, when it comes to the technical staff, to all the technical careers within the university, affirmative action has been working. Now, with respect to the faculty no, it hasn’t. And why is it not working? Because this is how universities interpret the law: look, we need to have, at least, three vacancies in order for one to be designated to a beneficiary of affirmative action, when in truth it’s rare that you have a competition with three openings. So the competition is actually for only one or two openings. In other words, in their reading of the law, the law does not apply. A lot of institutions have adopted this view, which is to say that the law never applies,” says Rios.

The professor also emphasizes that the reserve of vacancies proposed by law only applies to federal universities, and does not consider state, municipal or private institutions. Between 2012 and 2019, the number of self-identified black and brown professors climbed from 12% to 17%, while the number of self-identified white professors increased from 45% to 53%. The data from the last Census of Higher Education, published in 2020, indicate a minor change, still very far from the ideal, painting a picture that is still far from being representative of the black population in Brazilian higher education.

About the author: Jaqueline Suarez is a journalist and master’s student at the Fluminense Federal University (UFF), in Niterói. She is also a community journalist and independent documentary filmmaker. She lives in the favela of Fallet, in Santa Teresa, Central Rio.

About the artist: Jônatas Ariel is an illustrator and digital designer. Jônatas lives in the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro.

This article is the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” Follow our Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas series here.